Mid-Century Modern (1945-1965): The American Golden Age

The Mid-Century Modern movement (1945-1965) emerged in post-war America as a celebration of optimism, innovation, and democratic design. Born from the convergence of Bauhaus principles, Scandinavian simplicity, and American industrial ambition, this aesthetic revolutionized domestic interiors with its organic forms, bold colors, and functionalist ethos. More than a style, it embodied the aspirations of a generation seeking to build a better, more accessible modern world.

Los Angeles, 1949. In the hills of Pacific Palisades, Charles and Ray Eames complete their Case Study House #8, an architectural manifesto of postwar America. Steel, glass, and vibrant colors assemble into a lightweight structure open to the California landscape. While Europe laboriously rebuilds and the Bauhaus dissolves into emigration, America invents a new aesthetic language: Mid-Century Modern. This style, which would dominate 1945-1965, embodies the optimism of the victorious American superpower, unprecedented economic prosperity, and unwavering faith in progress.

Unlike Streamline, which stylizes objects to suggest speed, Mid-Century Modern privileges material authenticity and simplicity of form. Unlike Cranbrook Academy, which cultivates artisanal excellence, Mid-Century embraces industrial production and democratization. This aesthetic – clean lines, organic forms, vibrant colors, interior – exterior integration-radically transforms American housing and exports worldwide as a symbol of modern lifestyle.

What is Mid-Century Modern

The Mid-Century Modern designates the dominant style of American design from approximately 1945 to 1965, with roots as early as the late 1930s. It’s characterized by clean yet warm forms, natural materials (wood, leather) combined with modern materials (aluminum, fiberglass, plastic), and functionality that doesn’t exclude sculptural expression.

This movement distinguishes itself radically from contemporary European styles. Where Russian Constructivism privileged political austerity, Mid-Century celebrates consumerist prosperity. Where De Stijl imposed orthogonal geometry, Mid-Century cultivates organic curves. Where Art Deco reserved luxury for the elite, Mid-Century targets the rapidly expanding middle class.

The term “Mid-Century Modern” itself only appears in the 1980s, retrospectively invented to designate this 1950s-60s aesthetic. At the time, people simply spoke of “contemporary design” or “modern style.” This belated naming reflects the nostalgic rediscovery of a period perceived as the golden age of American design. The movement inscribes itself in the great history of design as a successful synthesis between European modernism and American pragmatism.

Historical & Cultural Context

America emerges from World War II as an uncontested superpower. With its territory intact and its economy booming, it experiences unprecedented prosperity. The GI Bill (1944) allows veterans to access higher education and homeownership. The middle class explodes demographically and economically. This generation, traumatized by the Depression and war, aspires to stability, domestic comfort, and family life in the new suburbs.

The technological context favors Mid-Century’s emergence. New materials developed during the war (molded plywood, fiberglass, plastic resins, aluminum) become available for civilian applications. Mass production techniques, perfected for the war effort, enable manufacturing quality furniture at affordable prices. This convergence of economic prosperity and technical innovation creates ideal conditions for democratic design.

California emerges as Mid-Century’s laboratory. Its mild climate enables architecture open to the exterior. Its distance from East Coast conventions favors experimentation. The film industry and aerospace attract talent and capital. Los Angeles, Phoenix, Palm Springs become epicenters of a new American aesthetic, more relaxed and hedonistic than austere European modernism.

The emigration of European designers fleeing Nazism considerably enriches American design. Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler (Austria), Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius (Bauhaus), Mies van der Rohe (Germany) bring European modernist rigor that they adapt to the American context. This encounter between European tradition and American pragmatism generates Mid-Century Modern.

The ideological context of the Cold War also influences the movement. Modern American design becomes a soft power weapon, proof of the capitalist lifestyle’s superiority. The USIA (United States Information Agency) organizes exhibitions and publications celebrating American design. Domestic comfort, household appliances, accessible furniture: everything demonstrates that American capitalism offers a better life than Soviet communism.

Aesthetic Characteristics

Mid-Century aesthetic is recognized by its balance between rigor and warmth. Forms are clean but not cold, functional but not utilitarian. This synthesis distinguishes Mid-Century from more austere European modernism and more superficial commercial Streamline.

Forms and Proportions

Organic forms dominate: soft curves inspired by nature, biomorphic volumes, fluid lines. Tapered legs become a stylistic signature: thin, angled, elegant. This visual lightness contrasts with the massive furniture of previous periods.

Horizontality structures architectural compositions. Houses stretch lengthwise, flat or slightly sloped roofs, low lines that integrate with the landscape. This horizontal emphasis evokes American vastness, suburban expansion, the conquest of space.

Modularity also characterizes Mid-Century. Reconfigurable shelving systems, combinable furniture, flexible spaces: everything reflects a modern and mobile lifestyle. George Nelson invents the storage wall, a modular storage wall that structures space without compartmentalizing it.

Materials and Colors

Mid-Century conjugates natural materials and modern materials with remarkable ease. Teak, a tropical wood with pronounced grain, becomes an emblematic material—warm, durable, elegant. American walnut, maple, birch bring their varied tonalities.

Modern materials integrate harmoniously: molded fiberglass for seat shells, aluminum for structures, formica for work surfaces, vinyl for coverings. These materials don’t seek to imitate traditional materials: they assert their modernity.

The chromatic palette privileges vibrant yet sophisticated colors: burnt orange, turquoise, mustard yellow, avocado green. These hues, combined with natural tones of wood and white surfaces, create warm and dynamic interiors. This chromatic boldness contrasts with the black-white-gray purism of European modernism.

Interior-Exterior Integration

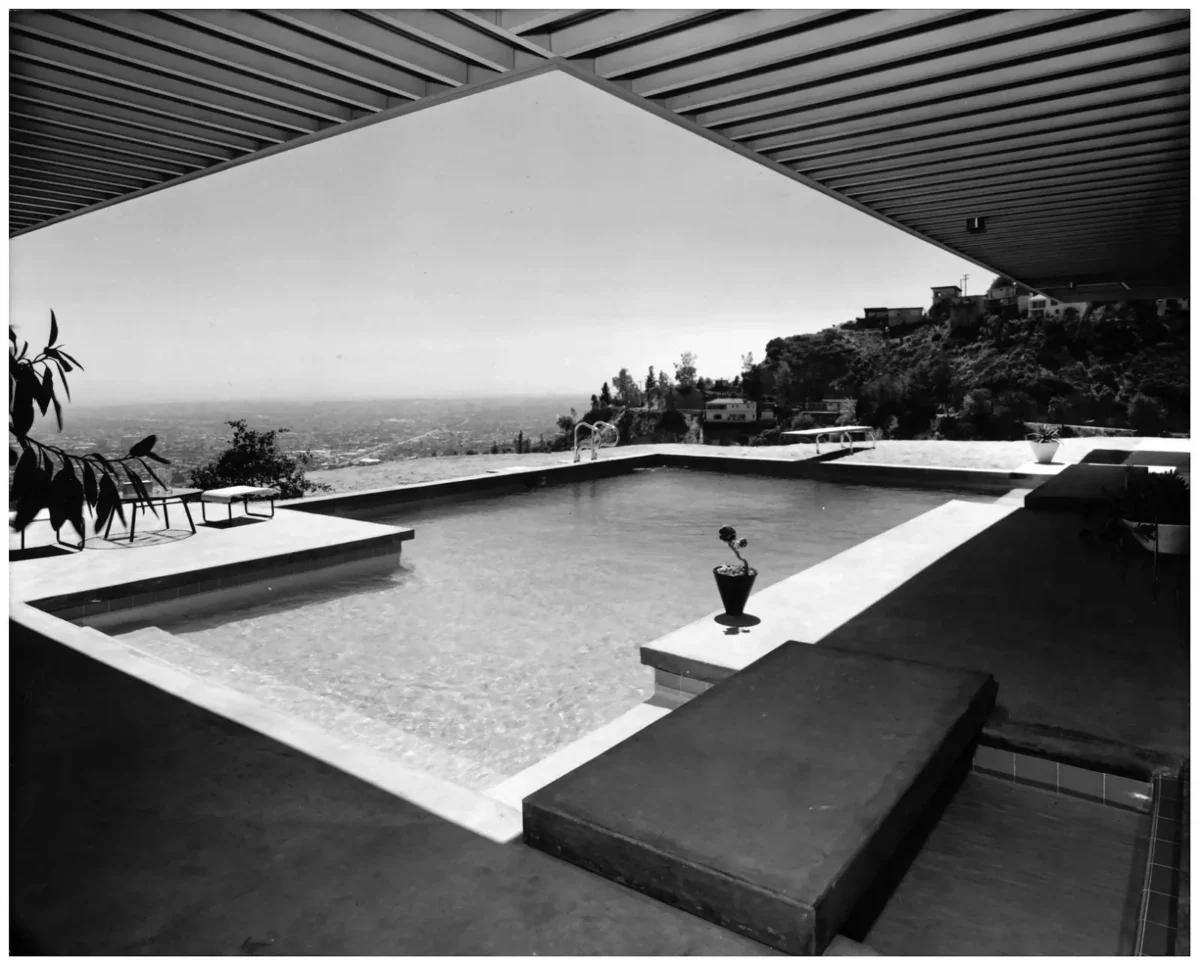

Mid-Century’s cardinal principle: abolish the boundary between interior and exterior. Curtain walls in glass, panoramic sliding doors, integrated patios create spatial continuity. This openness, unthinkable in European climates, becomes possible and desirable in California.

This integration also reflects a philosophy: living in harmony with nature, enjoying sun and fresh air, cultivating a direct relationship with the landscape. California architects like Richard Neutra or Pierre Koenig perfect this aesthetic of transparency and spatial fluidity.

Mid-Century Architecture

The Case Study Houses

The Case Study Houses program (1945-1966), sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine under John Entenza’s direction, constitutes Mid-Century’s architectural manifesto. The objective: design modern houses, industrially reproducible, affordable for the postwar middle class.

Case Study House #8 by Charles and Ray Eames (1949) becomes the program’s icon. Prefabricated metal structure, colored industrial panels, integration of found objects: the house functions as a three-dimensional collage. Its lightness, transparency, openness to nature perfectly embody Mid-Century aesthetic.

Case Study House #22 by Pierre Koenig (1960), photographed at night with Los Angeles glittering below, becomes the most famous image of Mid-Century architecture. This cantilevered house on a hill, entirely glazed, symbolizes American optimism and faith in technology.

Richard Neutra and Organic Architecture

Richard Neutra (1892-1970), Austrian architect emigrated to California, develops an architecture that fuses European modernism and California sensibility. His Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs (1946) illustrates his approach: pure geometric volumes, large glass bays, integration with the surrounding desert.

Neutra theorizes biorealism, the conviction that architecture must respond to human biological and psychological needs. His houses privilege natural light, ventilation, views of nature—principles that durably influence California residential architecture.

Joseph Eichler and Democratization

Joseph Eichler (1900-1974), visionary real estate developer, industrializes Mid-Century architecture for the middle class. From 1949 to 1974, he builds over 11,000 houses in the San Francisco area, applying Mid-Century principles to mass production.

Eichler homes—flat roofs, curtain walls, interior atriums, carports—bring modern design to ordinary families. This democratization fundamentally distinguishes American Mid-Century from European modernism, often reserved for a cultivated elite.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, photo Fastily, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Furniture and Industrial Design

Charles and Ray Eames

Charles (1907-1978) and Ray Eames (1912-1988), trained at Cranbrook, become the tutelary figures of Mid-Century furniture. Their approach—joyful experimentation, technical rigor, accessibility—defines the movement’s spirit.

Their emblematic creations transform modern furniture. The Lounge Chair and Ottoman (1956)—black leather, rosewood plywood shells, aluminum base—becomes the most iconic chair of the 20th century. Comfortable, elegant, technically sophisticated, it embodies Mid-Century’s success: accessible luxury, warm modernity.

But the Eameses also excel in economical mass-market furniture. Their molded fiberglass chairs (1950), molded plywood chairs (1946), wire mesh chairs (1951) democratize modern design. Produced by the hundreds of thousands, they equip schools, offices, homes. This duality—luxurious masterpiece and mass object—characterizes their approach.

George Nelson and Herman Miller

George Nelson (1908-1986), design director at Herman Miller from 1945 to 1972, structures the Mid-Century furniture industry. He recruits the Eameses, Isamu Noguchi, Alexander Girard, creating an unparalleled constellation of talents.

Nelson’s creations—Marshmallow Sofa (1956), Ball Clock (1949), Coconut Chair (1955)—conjugate formal sophistication and playful spirit. His Comprehensive Storage System (CSS, 1959) invents modern modular, flexible, evolving office furniture.

Eero Saarinen and Knoll

Eero Saarinen (1910-1961), also trained at Cranbrook, creates for Knoll Associates pieces that become Mid-Century icons. His Tulip Chair (1956) realizes his ambition: “to clear up the slum of legs” by creating a single-pedestal seat. This sculptural, futuristic form embodies the spatial optimism of the atomic age.

His Womb Chair (1948) offers a comfortable cocoon, a domestic refuge after the war years. The Tulip Table, the Pedestal Table: all his creations privilege formal purity and sculptural elegance.

Scandinavian Designers in America

American Mid-Century also integrates Scandinavian influence. Hans Wegner, Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl: their teak creations, with organic lines and refined craftsmanship, meet immense American success. This Nordic influence reinforces Mid-Century’s warm and natural dimension, distinguishing it from colder industrial modernism.

Graphic Design and Industrial Design

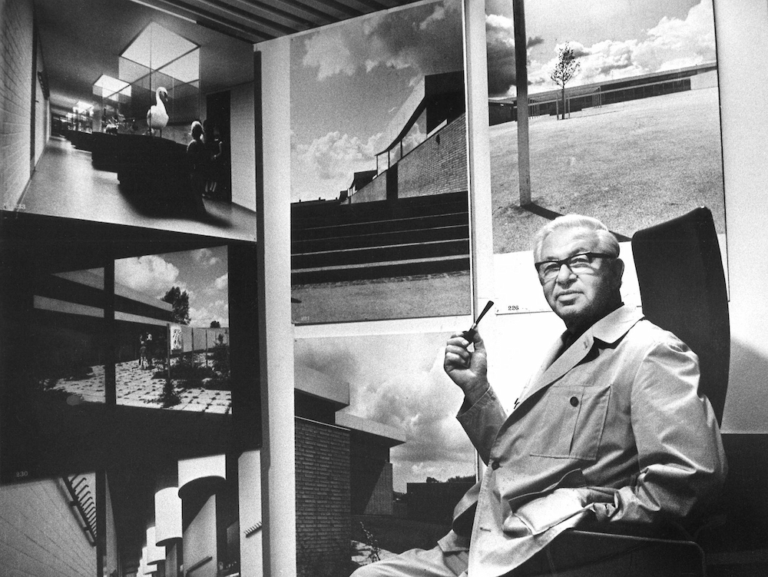

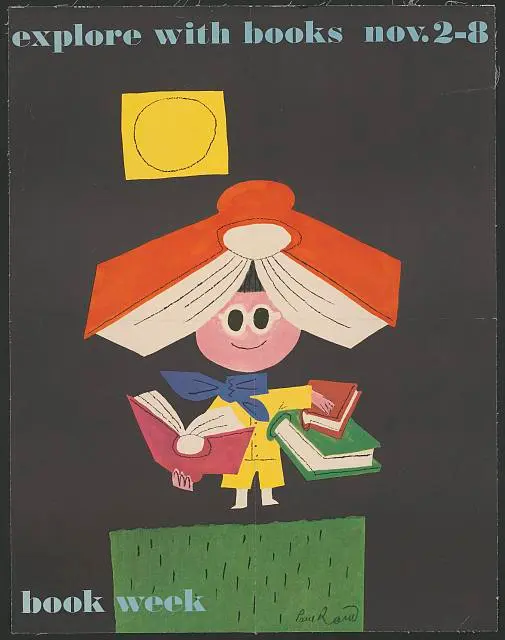

Paul Rand and Corporate Graphic Design

Paul Rand (1914-1996) revolutionizes corporate graphic design. His logos for IBM (1956), ABC (1962), UPS (1961) establish standards for modern corporate identity. Simple, memorable, timeless: his approach durably influences visual communication.

Mid-Century graphic design -asymmetric compositions, sans serif typography, dynamic photography, vibrant colors -breaks with academic heaviness. Saul Bass‘s posters for Hitchcock or Preminger films, Alexander Girard‘s packaging, Alvin Lustig‘s advertisements: everything testifies to a modern, optimistic, accessible aesthetic.

Product Design and Home Appliances

Mid-Century transforms everyday objects. Industrial designers likeRaymond Loewy, Henry Dreyfuss, Walter Dorwin Teaguecontinue their work initiated in Streamline, but with a more sober aesthetic. Home appliances shed their streamlining for purer, more honest forms.

Colorful plastic portable radios, televisions integrated into teak furniture, mixers with aerodynamic but functional forms: all these objects embody American domestic prosperity. Their careful design demonstrates that even utilitarian objects deserve aesthetic attention.

Influence and Legacy

American Cultural Dominance

Mid-Century Modern becomes the international style of prosperity in the 1950s-60s. Exported through Hollywood cinema, design magazines, official exhibitions, it symbolizes the American lifestyle that the entire world aspires to imitate.

This cultural dominance is particularly exercised in Western Europe (American ally) and Japan (occupied then allied). Film interiors, TV series, advertising: all adopt Mid-Century aesthetic. This planetary diffusion consecrates American cultural superpower.

Decline and Nostalgia

Mid-Century begins to decline in the 1960s. The emergence of postmodernism, critique of consumerism, oil shocks, suburban decline: everything contributes to the style’s rejection. The 1970s-80s privilege other aesthetics: brutalism, high-tech, postmodern.

But from the 1990s, a powerful nostalgia resurrects Mid-Century. The TV series Mad Men (2007-2015) popularizes the aesthetic with a new generation. Original Mid-Century furniture becomes collectible. Reissues multiply. This renaissance reflects regret for an era of optimism and prosperity.

Contemporary Influence

Mid-Century massively irrigates contemporary design. Current minimalist aesthetic inherits its sobriety. The concept of interior-exterior integration structures contemporary residential architecture. The idea that design must be accessible and democratic remains central.

Creators among today’s great names like Jasper Morrison, Naoto Fukasawa or Konstantin Grcic extend the Mid-Century approach: clean yet warm forms, honest materials, elegant functionality. The commercial success of brands like West Elm, CB2 or Article testifies to contemporary appetite for Mid-Century aesthetic.

Current Market

Original Furniture Value

The original Mid-Century furniture market has experienced spectacular appreciation since the 2000s. A first-edition Eames Lounge Chair can reach 15,000 euros. An original Womb Chair approaches 8,000 euros. Rare pieces by George Nakashima or Isamu Noguchi regularly exceed 50,000 euros.

This appreciation reflects several phenomena: growing rarity of well-preserved originals, museum recognition of Mid-Century, generational nostalgia, objective quality of pieces. Mid-Century furniture becomes patrimonial investment, testimony to a golden age of American design.

Reissues and Reproductions

Official reissues by Herman Miller, Knoll, Vitra remain accessible while maintaining exceptional quality. A reissued Eames Lounge Chair costs approximately 6,000 euros, a Womb Chair 3,500 euros, a DSW chair 400 euros. These prices, high but justified by quality, allow access to authentic designs.

The market for unauthorized reproductions also explodes. Of variable quality, often produced in Asia, they democratize (or vulgarize, depending on perspective) Mid-Century aesthetic. This massification testifies to popular appetite for the style but raises questions of intellectual property and quality.

Mid-Century Architecture

Mid-Century residential architecture experiences similar revaluation. Eichler houses, Case Study Houses, Neutra’s realizations: all see their value explode. Palm Springs becomes Mid-Century’s Mecca, with its annual Modernism Week attracting tens of thousands of visitors.

This architectural revaluation also raises preservation issues. Many Mid-Century houses are demolished or disfigured by insensitive renovations. Organizations like Docomomo (Documentation and Conservation of buildings, sites and neighborhoods of the Modern Movement) advocate for their protection.

Conclusion

Mid-Century Modern embodies the apex of postwar American cultural and economic power. By synthesizing European modernist rigor and American optimistic pragmatism, this movement creates an aesthetic that is both sophisticated and accessible, modern and warm, functional and expressive.

This synthesis radically distinguishes Mid-Century from its predecessors. Where Bauhaus imposes sometimes austere rigor, Mid-Century cultivates domestic warmth. Where Streamline stylizes superficially, Mid-Century privileges material honesty. Where Cranbrook maintains an elitist dimension, Mid-Century explicitly aims for democratization.

The movement’s spectacular success – millions of furniture pieces sold, thousands of houses built, planetary cultural influence- proves the validity of this approach. Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, George Nelson, Richard Neutra: these creators define what will be called “good design” for decades. Their furniture still equips offices, schools, homes worldwide today.

Mid-Century’s legacy remains ambivalent. On one hand, the movement demonstrated that quality design and mass production were not incompatible, that modernity could be human and warm, that aesthetic excellence was not reserved for an elite. On the other, its close association with American consumerism, suburbs, automobile lifestyle raises ecological and social questions.

Mid-Century’s contemporary renaissance reflects a complex nostalgia. It’s not just the aestheticb- organic forms, vibrant colors, natural materials- that seduces, but the optimism it embodies. In a contemporary world marked by climate anxiety, economic instability, geopolitical tensions, Mid-Century evokes an era when people believed in progress, when the future seemed bright, when design could improve daily life.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.