Wave Architecture: Immersion in the Heart of Diango Hernández’s Aesthetic

It was completely by chance that I discovered the work of artist Diango Hernández: it was an artistic coup de foudre.

The image is so perfect that at first I feared it might be AI! Oh, what do I see, these are his paintings on canvas!

I briefly explore Diango’s entire body of work… It’s all about structure, colors, and forms,it’s the whole “vibe” and this aquatic Ariadne’s thread of the wave (and transformation). In short, everything resonates in the work of this artist with an irresistible aesthetic.

This deserves our full attention! So it was decided, this time I’m taking you on a journey to discover the hypnotic work of Diango Hernández with Hart Design Selection.

Between Cuban Memory and Radical Design: Portrait of an Artist Reinventing Domestic Space

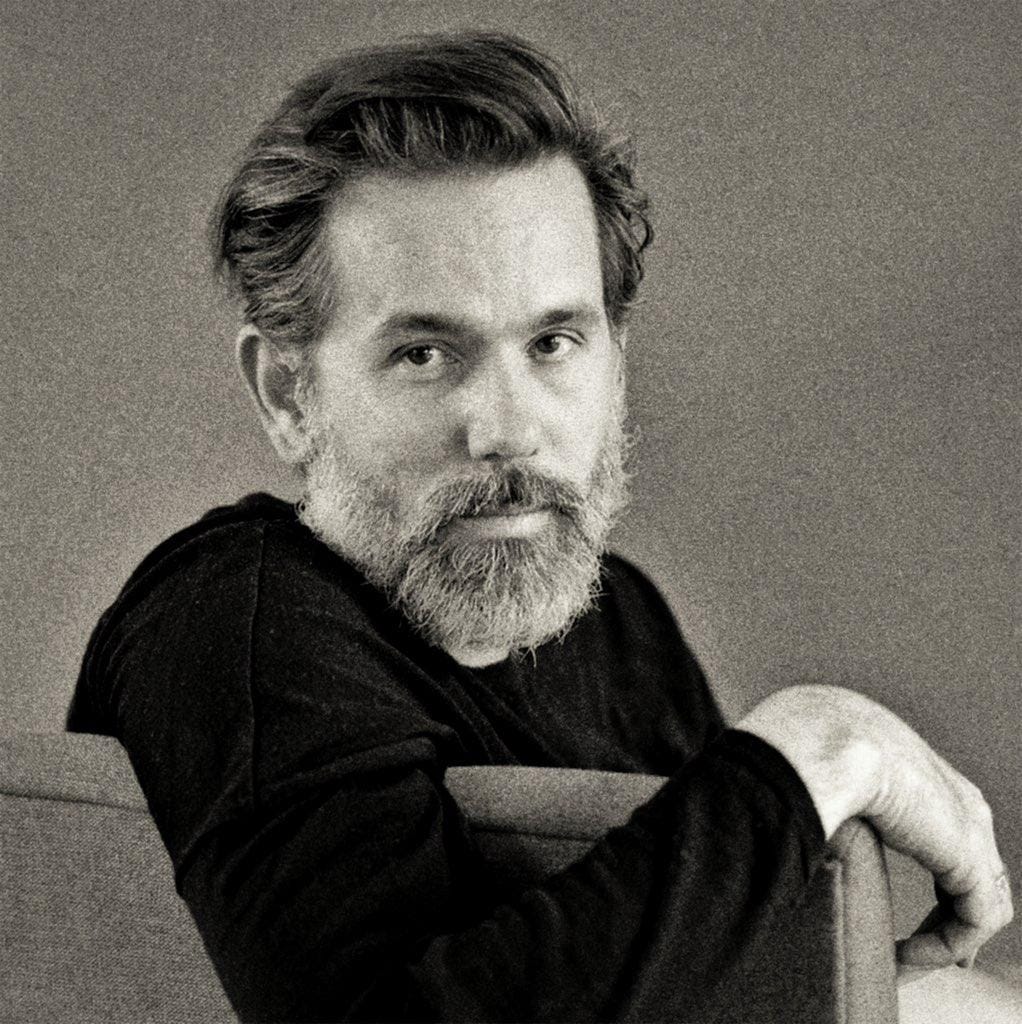

Who is Diango Hernández?

Diango Hernández was born in 1970 in Sancti Spíritus, Cuba. His journey began with studies in industrial design at the Havana Superior Institute of Design in the early 1990s, precisely when the island was experiencing its worst economic crisis following the collapse of the Soviet Union. This period, the Período Especial, profoundly shaped his practice: learning design in a country with neither materials nor resources forged a particular approach to creation.

In 1994, he co-founded Ordo Amoris Cabinet (The Order of Love) with Ernesto Oroza, Juan Bernal, Francis Acea, and Manuel Piña. This collective of artists and designers transformed scarcity into aesthetic language, creating sculptural installations from salvaged materials. They documented makeshift objects from everyday Cuban life, fans converted into sculptures, cans transformed into lamps. This aesthetic of necessity became the foundation of their work.

In 2003, Hernández left Cuba for Germany. He settled in Düsseldorf where he now lives between two worlds, two cultures. His first solo exhibition after this departure was titled Amateur (Frehrking Wiesehöfer, Cologne): more than 2,000 drawings created in Cuba, accompanied by fragile objects that resemble household appliances but don’t function. Drawing became a form of mental resistance, a way to capture a disappearing reality.

Since then, his work has been presented in major institutions: Venice Biennale (2005), São Paulo Biennial (2006), Kunsthalle Basel (2006), Hayward Gallery in London (2010), with a survey exhibition at MART in Rovereto (2011-2012). In 2009, he received the prestigious Rubens Award. Yet Hernández remains unclassifiable. As critic Timotheus Vermeulen wrote in Frieze Magazine, “his art defies easy categorization. He makes conceptual art yet carefully constructs pieces by hand like a craftsman. He is as much an inventor as he is an explorer.”

A Practice Between Art and Design

Today, Hernández works primarily in oil painting on canvas, but his training in industrial design remains omnipresent in his approach. His works oscillate between architectural plans and pure abstraction, between technical drawing and chromatic sensation. He produces for international galleries, notably Wizard Gallery in Milan, Marlborough Contemporary in London, and Alexander and Bonin in New York.

His works are held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, MART in Rovereto, and Inhotim Centro de Arte Contemporânea in Brazil. Diango is definitely a recognized figure in contemporary art, and his singular position at the crossroads of multiple disciplines is undoubtedly what makes his work both so rich and distinctive.

Methodologically, design remains central. In an interview with Francesco Dama, Hernández explains: “Through design, I learned how to study a problem and find solutions.” This methodical approach is evident in his series: each work seems to answer a precise formal question, exploring variations on a given theme.

Piscinas Olaistas: Impossible Pools

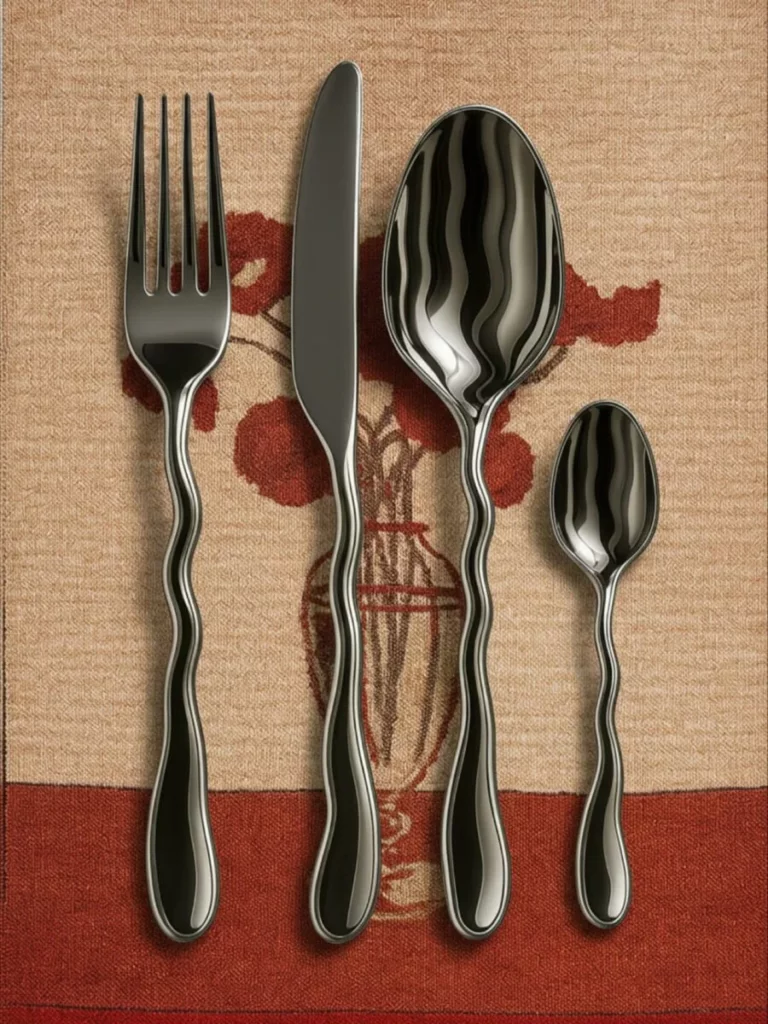

His current practice focuses on what he calls Olaismo, from ola, the Spanish word for wave. It’s not an artistic movement but a personal philosophy about what flows, changes, and transforms. “Waves are the language of the sea,” he says, “a language for creating images of a more fluid world, without rigidity.” This fluidity becomes the structuring principle of his recent work.

The Piscinas Olaistas constitute Hernández’s most emblematic series, developed between 2015 and 2025. These are paintings of imaginary pools, conceptual architectures that will never exist in three dimensions. Yet they are rendered with a precision that evokes architectural plans, aerial views, technical sections.

Visually, these pools are immediately striking: saturated color blocks—electric turquoise, fuchsia pink, solar yellow, bright orange meet in organic curves. The forms undulate, creating pools that you can’t tell if they’re viewed from above or from the side, flat or deep. The perspectives are deliberately impossible: multiple viewpoints coexist in the same image, as if the pool existed in a mental rather than physical space.

The visual identity follows a precise design genealogy: one thinks of the Ulm School, Cuban ICAIC posters from the 60s-70s, Memphis Milano. This idea that geometric forms and bright colors can carry political meaning without being didactic. But Hernández adds this liquid dimension, this instability that prevents any fixation.

These pools are never innocent. They evoke the public pools of tropical modernism, those that Cuban socialism promised to all—democratic leisure, utopian architecture. But they also carry the awareness of failure: those abandoned pools after the fall of the USSR, those unfulfilled promises. Water in Hernández’s work is always a political metaphor: that of clandestine crossings to Florida, migrations, family separations.

The series functions as a monument to loss, but a colorful, vibrant monument that refuses pathos. The Piscinas Olaistas are objects of impossible desire, we want them while knowing they cannot exist. It’s precisely this tension that makes them so powerful: they embody what modernist utopia promised and never delivered.

Bathrooms: Tiles and Domesticity

Less known than the pools but equally important, Hernández’s works on bathrooms explore domestic architecture with the same approach. He works extensively with tile patterns, those geometric surfaces that structure the intimate space of the Cuban home.

In these paintings, tiles become graphic elements, almost abstract. The colors are sometimes softer than in the pools, pale pinks, water greens, off-whites, but the approach remains the same: deconstruct domestic space to make it a mental architecture. Hernández’s bathrooms have that “total” design that reminds me of Verner Panton’s psychedelic installations from the 60s.

This is consistent with his history: in Cuba, the bathroom is a space charged with meaning. It’s where failing infrastructures, water supply problems, and the necessity to improvise manifest most clearly. Hernández transforms these material constraints into visual language. His tiles are not mere decorative patterns: they carry the memory of Cuban homes, the Soviet heritage in domestic design, the promises of a modernity that never quite arrived.

What’s interesting about these works is that they’re completely rooted in design culture. One could imagine these patterns actually applied, produced by a bold tile manufacturer, installed in a concept hotel. There’s a porosity between artwork and design object that makes Hernández’s work particularly relevant for thinking about contemporary space.

Windows: Filters and Transparencies

The Windows series, developed notably in 2024-2025, constitutes the third major chapter of this architectural exploration. Hernández paints windows seen frontally, but through a filter that blurs everything: a semi-transparent veil, a wavy texture that evokes frosted glass or water in motion.

These windows are troubled thresholds. We glimpse forms behind, sometimes human figures, sometimes landscapes, sometimes nothing precise. Everything is blurred, imprecise, yet strangely rich in visual textures. It’s Olaismo applied to the window: the idea that between us and reality there’s always an element that transforms, deforms, liquefies what we see.

The formats are often large (170 x 130 cm for some canvases) creating a strong physical presence. Facing these painted windows, we find ourselves in the position of the viewer looking through, trying to pierce the veil. But the transparency promised by the window is systematically compromised, troubled.

There’s something profoundly Cuban in these opaque windows. In Havana, windows open onto private interiors, domestic lives that unfold half-publicly. But they’re also borders: between inside and outside, between the island and the rest of the world, between what’s shown and what’s hidden. Hernández doesn’t paint windows that open, he paints windows that filter, mediate, transform the gaze.

Towards an Affective Architecture

What connects these three series – pools, bathrooms, windows -is the same ambition: to transform domestic architecture into affective space. Hernández doesn’t draw plans to build; he creates images to inhabit mentally. His architectures are physically impossible but psychologically necessary.

There’s real generosity in this approach. Rather than just noting the failure of modernist utopias, those abandoned pools, failing infrastructures, unfulfilled promises, Hernández makes something beautiful, vibrant, usable from them. Nostalgia becomes creative energy rather than paralysis.

And then there’s this question that remains open: why hasn’t anyone seized this universe for a real architectural project? The Piscinas Olaistas, the tile patterns, the window aesthetic… this entire visual universe would be perfect for a concept hotel, a collaboration with a bold architect. Imagine a place where we could truly inhabit this liquid utopia, if only for one night?

It would be a real statement: transforming these paintings into an immersive experience, giving body to these impossible architectures. From pool to bathrooms, from common areas to rooms, the entire Olaista universe rendered in three dimensions. A project that would raise questions about what we expect from architecture, about how we inhabit political memory through design.

Meanwhile, Hernández continues to paint. The pool series grows with new variations (the most recent dates from 2025), windows multiply, tiles unfold. His work reminds us that architecture is never neutral, that a pool is never just a pool, that a window always carries more than light.

In Olaismo according to Hernández, the wave doesn’t need the sea to exist. It only needs our capacity to imagine other forms of life, other ways of inhabiting our memories and desires. Pools to dive into mentally, windows where the gaze becomes troubled, tiles where history is read in patterns.

Diango Hernández lives and works between Düsseldorf and Havana. His works are held in the collections of MoMA (New York), PAMM (Miami), MART (Rovereto), and Inhotim (Brazil). Represented by Wizard Gallery (Milan), Marlborough Contemporary (London), and Alexander and Bonin (New York).

Official website: olaismo.com

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.