The Napoleon III Style : Splendor and Innovation in the Second Empire

Do you know the Napoleon III style?

Do you know the Second Empire style, also known as Napoleon III? This French decorative style is historically positioned after the Louis-Philippe style and before the Art Nouveau style. It should not be confused with the Empire style, which dates to the very beginning of the 19th century and corresponds to the reign of Napoleon I (Napoleon Bonaparte).

The reign of Napoleon III marked a revolution in French art de vivre. After the enforced economies under Louis-Philippe, France rediscovered splendor and ostentatious consumption.

Second Empire: An Era of Transformation

This period, which we now envision as eighteen prosperous and brilliant years, ended dramatically with the double catastrophe of the Prussian invasion and the Paris Commune.

Essential chronology:

• 1852-1870: Second Empire political period (18 years)

• 1852-1890: Stylistic influence (nearly 40 years)

• International equivalent: English Victorian style

The Power of the Feminine

This era was remarkably dominated by feminine influence. Empress Eugénie reigned almost as much as her husband, while Paris saw the birth of new courtesans who became public figures.

La Païva (who would give her name to a famous private mansion), Cora Pearl, and many others influenced the fashion and tastes of their time.

A new bourgeois class emerged and appropriated the luxury once reserved for the aristocracy. For the first time, luxury – or at least its appearance – became accessible to a broader social stratum.

This democratization of refinement profoundly transformed French interiors and laid the foundations for our contemporary art de vivre.

Revolution of Mentalities

It was now women who chose the furniture, replacing men and architects in this traditional role.

This era also marked the “reign” of the upholsterer, an artisan who became indispensable to interior decoration.

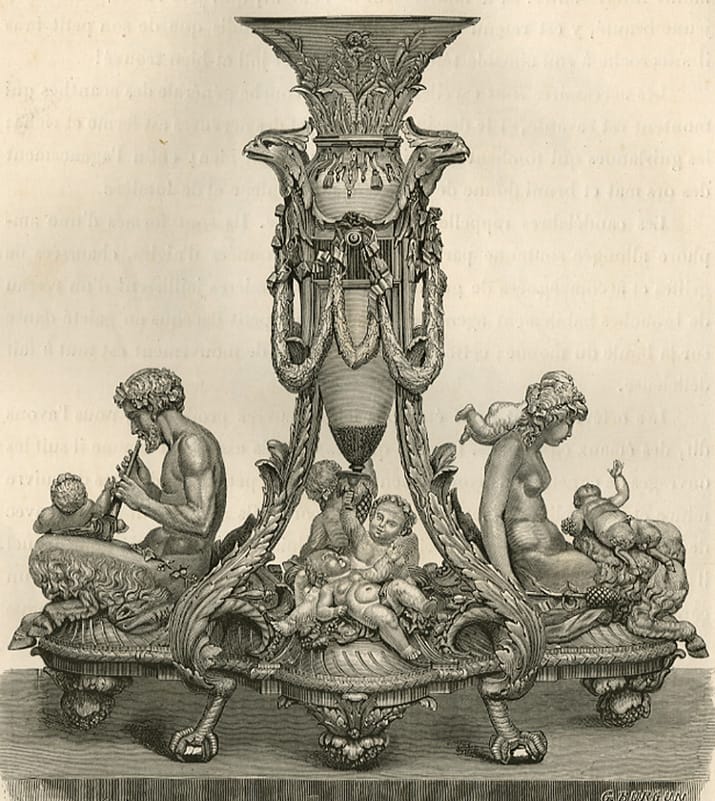

The aesthetic of the period celebrated the female form: sculpted nudes supported lamps and clocks, adorned salons, testifying to an assumed sensuality that characterized the decorative art of the Second Empire.

Arts: Between Tradition and Revolution

All-Powerful Academicism

The official art of the Second Empire favored imposing academicism. Alongside master Ingres, a constellation of official painters shaped the taste of the era.

Thomas Couture (Manet’s master), Franz Xaver Winterhalter (the court’s official portraitist), Jean-Léon Gérôme (specialist in orientalist scenes) dominated the official Salons.

Alexandre Cabanel (author of “The Birth of Venus”) and Ernest Meissonier (virtuoso of historical detail) completed this triumphant academic school.

Revolution in Progress

Parallel to this official art, a revolutionary avant-garde emerged in the shadow of institutions.

Gustave Courbet scandalized with his raw realism, Honoré Daumier sketched society with biting irony, Édouard Manet prepared the advent of impressionism.

The famous Salon des Refusés of 1863, created by Napoleon III himself, gave a platform to artists rejected by official art, thus opening the paths to modern painting.

In sculpture, the era particularly shone with Antoine-Louis Barye (master of animal sculpture), François-Joseph Duret, Auguste Clésinger, and Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (future master of Rodin).

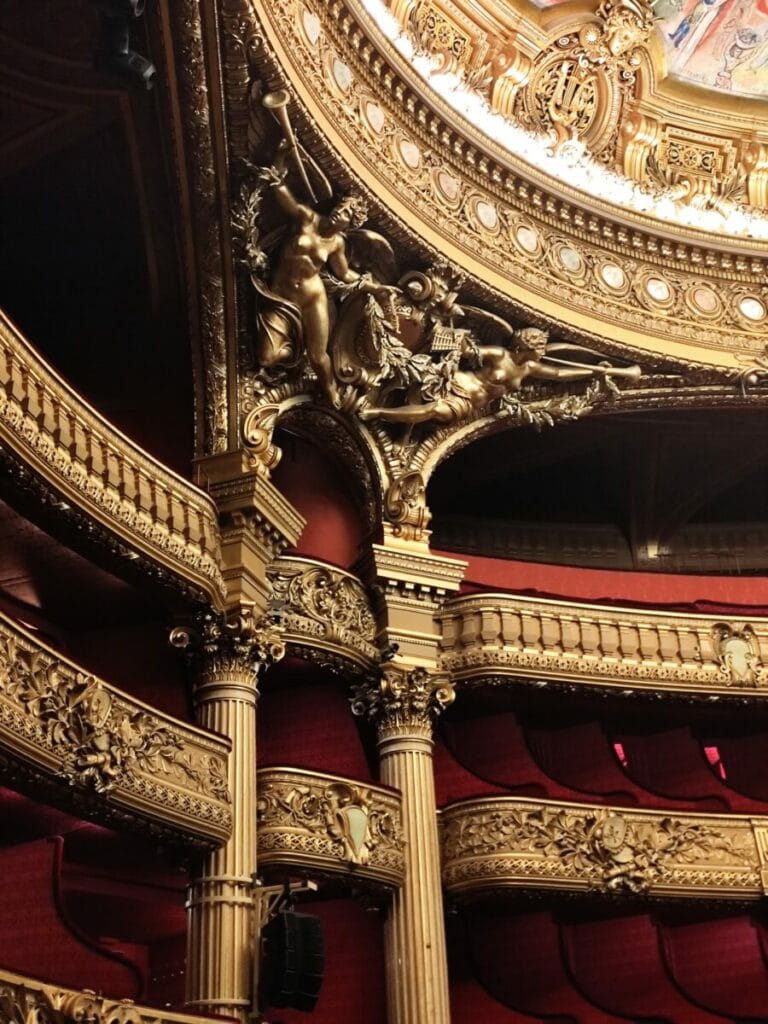

But it was Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux who truly dominated the sculpture of the era, notably with his revolutionary works for the Paris Opera.

Napoleon III Architecture:

The Haussmannian Metamorphosis

The Great Works (1852-1870): Under the impetus of Napoleon III and Prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Paris underwent the greatest urban transformation in its history.

The Haussmannian project revolutionized all aspects of Parisian urbanism: creation of grand boulevards (Boulevard Saint-Germain, Boulevard Saint-Michel), strict regulation of harmonized facades.

The development of green spaces (Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, Monceau and Buttes-Chaumont parks) transformed urban quality of life.

The modernization of street furniture, the revolution of sewers and water supply networks made Paris a modern capital.

Garnier and the Architectural Controversy

Architect Charles Garnier (creator of the Opera) and other artists denounced the “stifling monotony” of this monumental architecture.

Writer Émile Zola immortalized in “La Curée” the real estate speculation and corruption linked to these massive urban transformations.

This urban work, violently criticized by some contemporaries then forgotten in the 20th century, was finally rehabilitated after the discrediting of post-war urbanism.

It still conditions the daily use of Paris today and shapes the worldwide representation of the French capital.

A modern Paris of grand boulevards and open squares now overlays the old Paris of picturesque alleyways.

Artists and architects denounced the stifling monotony of this monumental architecture. Politicians and writers questioned the extent of speculation and corruption.

Many criticisms focused on fundamental motives and eventually brought down Prefect Haussmann in disgrace.

A New Habitat: Triumphant Eclecticism

In Paris renovated by Haussmann, the great architectural achievements were marked by eclecticism, an audacious mixture of reinterpreted historical styles.

Architects Hector Lefuel (completion of the Louvre), Gabriel Davioud (Châtelet theaters), and Charles Garnier (Opera) embodied this new creative trend.

Theoretical Revolution

The work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc on Gothic architecture and the first uses of iron in construction announced a radical renewal.

Jacques Ignace Hittorff (Gare du Nord), Victor Baltard (Les Halles de Paris), Henri Labrouste (Sainte-Geneviève Library), and Louis-Auguste Boileau were the pioneers of this constructive modernity.

The rise of industry, transport and commerce imposed metallic architecture and enabled innovative creations of unparalleled audacity.

The Eiffel Tower (built for the 1889 Exhibition) would symbolize the culmination of this technical and aesthetic revolution.

The decorative arts experienced the beginnings of industrialization and adopted forms from the Renaissance and 18th century (Louis XV and Louis XVI).

The furniture of the Fourdinois or Alfred Beurdeley, the bronzes of Guillaume Denière or Barbedienne democratized decorative luxury.

The goldsmithery of Froment-Meurice, the Fannière family, Christofle, the jewelry of the Falize family interpreted these styles according to the dominant taste for luxury and comfort.

Sumptuous tapestries, refined trimmings, soft buttoning characterized this aesthetic of abundance.

Napoleon III’s apartments at the Louvre, decorated by Hector Lefuel, offer the perfect example of this sumptuous style where each salon rivaled in richness.

Furniture and Seating: Innovation and Nostalgia

Major technical innovation: In the mid-19th century, the disadvantages of wood’s hygroscopicity were remedied by developing the revolutionary process of veneering.

This technique allowed for a more durable and aesthetic finish, revolutionizing the furniture arts.

Artisans used a palette of noble woods: pear and beech stained black for structures, solid oak for robustness, mahogany, rosewood or ebony veneers for elegance.

The inlay of precious woods, mother-of-pearl and ivory reached summits of technical and artistic refinement.

Decorators innovated with enamel plates, porcelain, and painted decorations on dark wood creating unprecedented chromatic effects.

Industrial innovation: Papier-mâché pressed in a mold revolutionized furniture production and democratized access to decorative furniture.

This technique made it possible to create seats and pedestal tables at lower cost, making beauty accessible to the middle bourgeoisie.

The era drew tirelessly from the past: Gothic wardrobes, Renaissance beds, Louis XV tables and bonheurs-du-jour testified to this creative nostalgia.

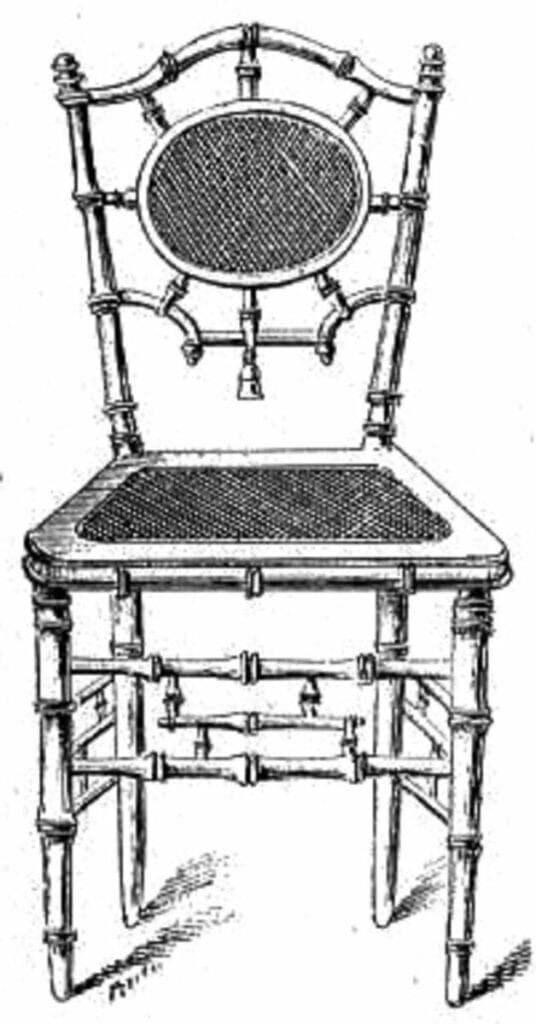

Exoticism also seduced with English Chippendale chairs, “Chinese” furniture, or those from the Arab world and notably inspired by the Ottoman empire, all reflections of the Napoleon III style’s taste for the elsewhere.

The ingenuity of manufacturers created an almost infinite range of seats, responding to the new needs of bourgeois sociability. Among the major characteristics: Second Empire interiors were distinguished by their deliberate “clutter.”

The multiplicity of seats and the proliferation of small tables created an aesthetic of abundance and unprecedented comfort.

Furniture Classification: Two Distinct Universes

Furniture Inspired by Ancient Styles

Although the general structure and decorative elements resembled originals, style copies were distinguished by revolutionary practical innovations.

The addition of casters for mobility, the omnipresence of buttoning for comfort, and the profusion of fringes for ornamentation transformed furniture usage.

The decorative structure, less varied than in previous eras, now invaded parts of the seat formerly left bare, creating an aesthetic of total envelopment.

We then find Louis XV and Louis XVI style armchairs with revival of classic lines and systematic addition of buttoning.

The Gondola armchair inherited from the Directoire but adapted to bourgeois taste for comfort with softer upholstery.

The Crapaud armchair, a perfected Louis-Philippe creation, became the archetype of comfortable and intimate seating.

The Voltaire appeared previously with the Louis-Philippe style, taking up the 18th-century winged bergère but revisiting it for reading and new domestic leisure activities.

Henri II “Renaissance” chairs offered a romantic interpretation of the 16th century, mixing historical nostalgia with modern techniques.

Louis XV and Louis XVI chairs were modified versions with casters and buttons, adapted to new mobility uses.

Traditional sofas consisted of Louis XV, Louis XVI or crapaud armchairs with widened seats to accommodate women’s imposing crinolines.

Authentic Second Empire Creations

Emblematic innovation: The Second Empire invented rope-shaped legs, a unique stylistic signature of the era.

This decorative innovation, imitating marine rope braids and knots, reflected the maritime and colonial expansion of Napoleonic France.

Women’s imposing crinolines favored the multiplication of backless seats, creating new furniture typologies.

Poufs became widespread: round, low, buttoned seats, adorned with a flounce or fringe that elegantly concealed the legs.

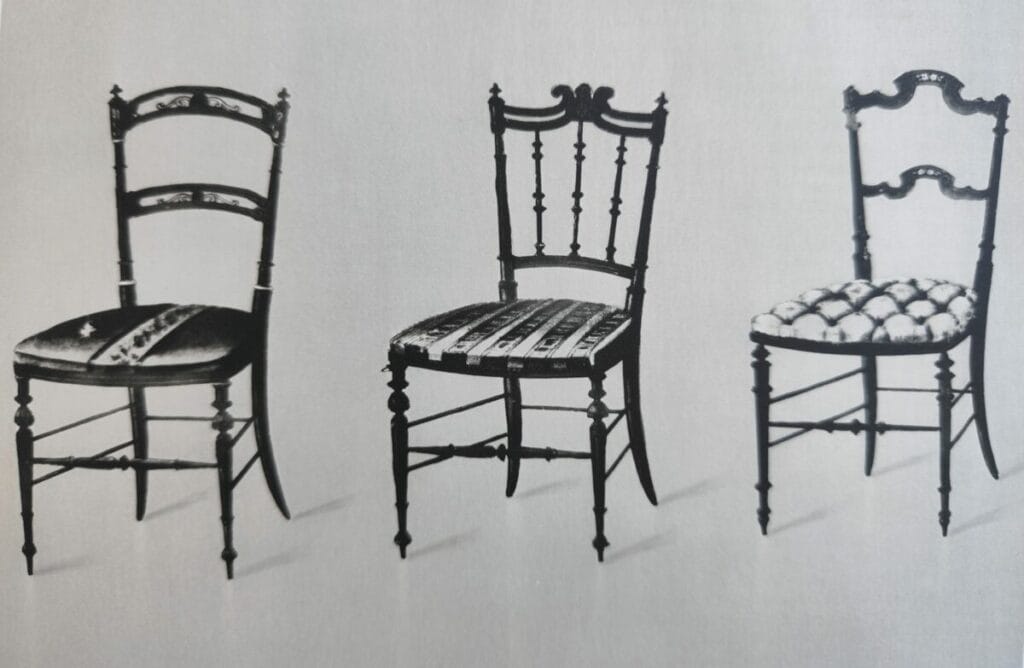

Flying Chairs

A flying chair designates a small lightweight chair, without armrests with an upholstered or caned seat, designed to be easily moved as needed. Present in bourgeois and aristocratic salons, it allowed for quick reorganization of space to accommodate guests, musicians or conversation groups. Of careful manufacture, often in turned or carved wood, it adopted the curved forms and refinement typical of the Napoleon III style, perfectly embodying the mobile and convivial elegance of the era.

Confident Armchairs

Social as much as aesthetic innovation, the confident consisted of two armchairs joined and inverted, united by an upper crosspiece of the S-shaped backrest.

In this revolutionary type of seat, no wood appeared. Entirely buttoned and “skirted,” it was adorned with light and shimmering colored fabrics.

It facilitated intimate conversations in bourgeois salons and embodied the new sociabilities of the era.

The Indiscreet: An audacious variant of the confident, the indiscreet united three armchairs joined by an upper crosspiece in the shape of a three-blade propeller.

Like the confident, it was a seat with entirely covered wood, symbol of new bourgeois sociabilities and their theatricality.

The Chauffeuse: Adaptation and Innovation

The two types used in the previous era were subtly modified to respond to new domestic and clothing uses.

Buttoned chauffeuse: Of the same manufacture as the crapaud armchair, but without arms to facilitate feminine use.

Tassels and fringes trailing to the floor concealed legs equipped with practical casters, responding to the mobility needs of women in crinolines.

High-back chauffeuse: The low and rectangular buttoned seat contrasted with a backrest of very variable forms.

Gilded and carved wood, black lacquered wood with mother-of-pearl inlays, or decorative papier-mâché testified to the creative eclecticism of the era.

Remarkable Stylistic Innovations

Chair and armchairs with medallion backrest: The seat was sometimes caned (traditional technique brought back to contemporary taste) and rested on four slightly curved legs.

Two posts supported a hollowed medallion, generally in dark wood inlaid with lacquer or painted, creating an elegant transparency effect.

“Bamboo” chair: The rectangular buttoned seat contrasted with a structure imitating exotic bamboo, testimony to orientalist fascination.

Legs, backrest uprights and crosspieces reproduced this aesthetic, either in dark wood or patinated bronze.

Chair and “Rope” Poufs: Naval and Colonial Symbol

Pure innovation of the Second Empire, this seat was distinguished by its luxurious damask silk covering contrasting with its sculpted structure.

The legs, backrest and belt in black wood imitated through their sculptures the braids and knots of rope. This creation evoked French maritime power and the colonial expeditions that marked Napoleon III’s reign.

“Chinese” Chair: Salon Exoticism

Adaptable to normal or low height, this creation with a rectilinear backrest imitated the “fantasy China” dear to the era.

Black and gold lacquered bars, mother-of-pearl or ivory inlays created a salon orientalism, reflection of tastes for the exotic without authenticity.

“Charivari” Chair: Daily Theatricality

Buttoned seat with backrest consisting of a series of turned and gilded bars, embodiment of Second Empire theatricality.

These chairs, still offered today by rental companies for receptions, testify to an era when even everyday furniture had to be spectacular.

The Stool: Buttoned Simplicity

Square or slightly rectangular, the stool was systematically buttoned according to the dominant aesthetic of the era.

Its characteristic legs included 4 short legs joined by an X-shaped crosspiece, creating perfect stability for feminine activities.

The Borne: Revolutionary Sociability

This audacious creation united three two-armed sofas backed against a triangular base, revolutionizing the codes of bourgeois sociability.

This base was sometimes topped with an imposing ornamental motif in bronze, ceramic or gilded wood, transforming the furniture into total artwork.

The decorative element could be a flowering planter, transforming the furniture into a true perfumed and colorful indoor garden.

Entirely covered in fabric, this piece of furniture embodied bourgeois art de vivre in its most theatrical and social dimension.

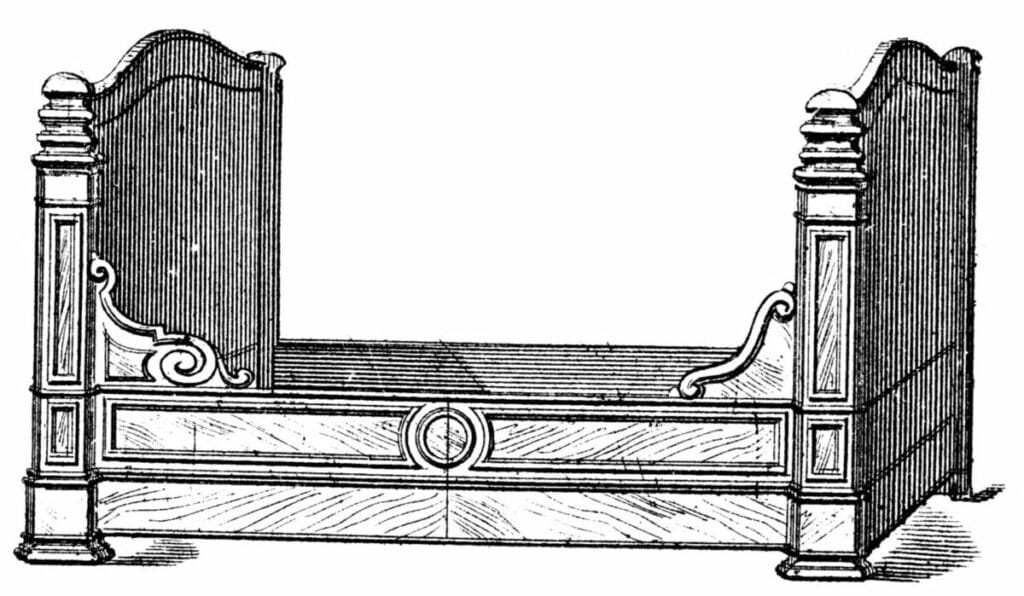

Beds: Renaissance Grandeur

Beds adopted the Renaissance type with heavy canopies resting on four twisted columns or sculpted caryatids.

Made of solid oak or walnut, they could present two unequal headboards (head headboard higher than the foot one).

This practical and aesthetic innovation facilitated reading in bed and testified to the evolution of domestic customs.

Tables: Decorative Eclecticism

Dining tables testified to the ambient eclecticism with their copies – sometimes mediocre but always ambitious – of reinterpreted ancient styles.

Louis XVI style round tables: Neo-classical elegance adapted to the new uses of the bourgeoisie and Haussmannian spaces.

Renaissance style rectangular tables: Historical monumentality for grand bourgeois receptions and social status display.

The Masters of Napoleon III Style

The Second Empire marked the golden age of French decorative arts, a period when artisanal excellence met industrial innovation to create a distinctive style.

This exceptional era saw the birth of a generation of decorators, architects and artisans who durably defined the French art de vivre.

The Visionary Architects of the Second Empire

Charles Garnier (1825-1898) perfectly embodied the creative spirit of the era with the Paris Opera (1861-1875), a true architectural manifesto of the Second Empire.

His revolutionary conception integrated architecture, painting, sculpture and decoration in a global vision, creating what contemporaries already called the “Napoleon III style.”

Garnier personally supervised every decorative detail, from the seventeen different colors of the facade to the sumptuous gilded interiors, establishing a model of total art that would durably influence European architecture.

The Garnier Opera represented more than a monument: it was a decorative laboratory where the greatest artists of the era collaborated.

Paul Baudry devoted ten years to painting the ceilings of the grand foyer with his thirty mythological compositions, while Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux revolutionized decorative sculpture with “The Dance.”

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) brought an essential theoretical dimension to the movement with his creative restoration of Pierrefonds Castle for Napoleon III.

He demonstrated his ability to reinvent historical architecture with modern techniques, developing a rationalist vision of decoration where each ornamental element justified its function.

Artisanal Excellence: Cabinetmakers and Creators

Beyond the famous Fourdinois and Beurdeley, a constellation of exceptional artisans animated the Parisian workshops of the Second Empire.

The Jeanselme House, heir to the prestigious Jacob family since 1847, supplied the palaces of Louis-Philippe and Napoleon III.

Its creations, fruit of collaborations with sculptors Carrier-Belleuse and Clésinger, perfectly illustrated the total art of the Second Empire where cabinetmaking and sculpture harmoniously blended.

Paul Sormani (1817-1877), an Italian established in Paris, revolutionized furniture art through his masterful copies of 18th-century masters.

Employing one hundred and fifty workers in 1867, his manufactory produced for Empress Eugénie creations in fruit wood marquetry of exceptional finesse.

Jean-Pierre Tahan (1813-1892), nicknamed the “Prince of small cabinetmaking,” embodied technical innovation with his porcelain marquetry patent.

His creations for Napoleon III’s office at the Tuileries mixed French tradition and technical innovations, illustrating the adaptability of art craftsmanship.

The Christofle House transformed goldsmithery by acquiring galvanoplasty patents in 1842 for one hundred and fifty thousand francs.

This technical revolution made it possible to democratize silver-plating while preserving aesthetic quality. The aluminum centerpiece created for Napoleon III in 1858 demonstrated the creative audacity of the era.

The Creative Ecosystem of Faubourg Saint-Antoine

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine constituted the beating heart of French craftsmanship, heir to the privileges granted by Louis XIV in 1657.

This district concentrated cabinetmakers, sculptors, gilders and varnishers in exceptional creative emulation where secular know-how was transmitted and enriched.

The Langlois and Martin families for varnishes, the Grohe workshops for luxury cabinetmaking, created an artisanal ecosystem of incomparable richness.

The École Boulle, founded in 1886, institutionalized this transmission by training cabinetmakers, upholsterers and sculptors according to proven methods.

The renaissance of Boulle marquetry perfectly illustrated the spirit of the Second Empire with the superposition of precious materials: tortoiseshell, copper, mother-of-pearl, ivory.

National Manufactories: Excellence and Innovation

The Gobelins, Sèvres and Beauvais, under the unified direction of Pierre-Adolphe Badin, launched an ambitious decorative program for the imperial palaces.

The tapestries “The Five Senses” after cartoons by Diéterle, Baudry and Chabal-Dussurgey demonstrated the manufactories’ capacity to create original decorative art.

The 1867 Universal Exhibition internationally consecrated this French excellence and definitively established French supremacy in decorative arts.

The Legacy of Napoleon III Style

The lasting impact of the Second Empire:

Beyond its historical dimension, the Napoleon III style durably revolutionized French art de vivre by democratizing luxury and feminizing decoration.

It laid the foundations of the modern furniture industry and our contemporary conceptions of domestic comfort.

This pivotal period saw the birth of mass consumption of beauty, a major sociological phenomenon that transformed French society.

For the first time in French history, a large bourgeoisie accessed aesthetic pleasures once reserved for the court aristocracy.

This social revolution translated into a decorative profusion that still characterizes our representation of “French taste” in the world today.

Feminine Revolution:

The Second Empire consecrated feminine influence in decorative art, an aesthetic emancipation that announced the social transformations of the 20th century. This feminization partly explains the new attention paid to comfort and intimacy in modern interior design.

Nostalgia, Exoticism and Innovation

The genius of the Napoleon III style resided in its capacity to reconcile nostalgia and innovation, tradition and nascent industrial modernity.

While the era drew abundantly from the historical repertoire (Renaissance, Louis XV, Louis XVI), it simultaneously invented revolutionary new forms.

Rope legs, confident, borne and new techniques (systematic buttoning, industrial papier-mâché) testified to this exceptional creativity.

French style under Napoleon III radiated throughout Europe and durably influenced world decorative arts through its technical excellence.

The 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris consecrated this French aesthetic hegemony and spread Second Empire innovations worldwide.

Today still, the Napoleon III style fascinates collectors and decorators through its successful synthesis between tradition and modernity. Its creations, long disdained in favor of modernist aesthetics, are experiencing a spectacular renewal of interest on the international art market.

Auction sales reach peaks for authentic pieces, while contemporary reproductions draw largely from its formal innovations.

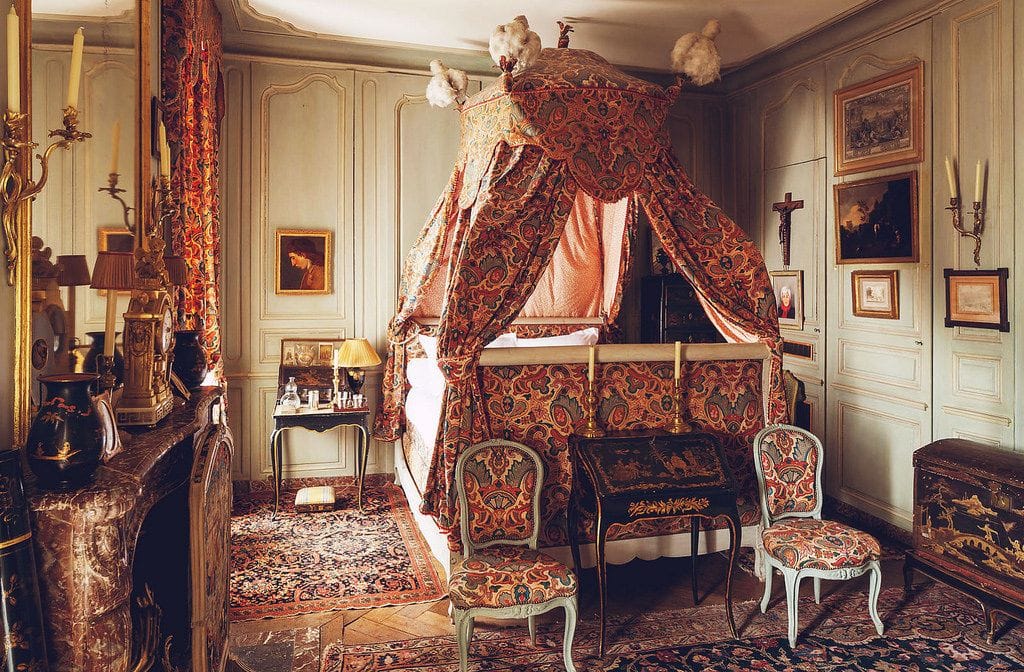

Jacques Garcia: The Contemporary Heir to Napoleon III Genius

Jacques Garcia (born 1947) embodies the contemporary renaissance of Napoleon III style with exceptional talent for reinterpreting this heritage.

Trained at École Penninghen, this son of a Spanish heating technician developed an early passion for decorative art by browsing flea markets.

His creative philosophy extends “from zen minimalism to neo-gothic overload, from the exoticism of the return from Egypt to Napoleon III folly.”

Hotel Costes (1996) marked his international consecration and revolutionized Parisian hospitality through its decorative audacity. Garcia deployed an assumed neo-Second Empire: Napoleon III red and purple velvet thrones, theatrical alcoves, neo-gothic chandeliers, antique bas-reliefs.

This “sexy and grand style” creation inspired an entire generation of decorators and durably transformed French hospitality art.

The Modern Reinterpretation of Historical Codes

Garcia’s philosophy rests on intimate knowledge of classical rules that he freely reinterprets with modern creativity.

“The beauty rules defined by the ancient world are a solid foundation on which I rely without ever getting bored,” he explains.

This approach explains his capacity to modernize the Napoleon III heritage without betraying it, creating an authentic contemporary decorative language.

At Château du Champ-de-Bataille, restored over twenty years, Garcia developed his most accomplished decorative laboratory. This “thought of eternity” mixed collections of furniture of royal provenance, objects dispersed under the Revolution and contemporary creations.

The forty-five hectares of gardens, Europe’s largest private garden, completed this vision of total art inherited from the Second Empire. His modernization techniques combined heritage respect and contemporary adaptation with perfect mastery of proportions.

The subdued lighting created by engraved Cordoba leathers, noble materials (malachite, onyx, porphyry) associated with modern technologies illustrated his know-how.

The International Influence of French Style

More than seventy hotels today bear Garcia’s signature: Wynn Las Vegas, Victor Hotel Miami, La Mamounia Marrakech.

This international expansion propagates French art de vivre heir to the Second Empire, demonstrating the contemporary relevance of this heritage.

His Baker Furniture collection (2004), “inspired by Napoleonic extravagance,” industrially translated his decorative vocabulary.

Garcia collaborates closely with the last French master artisans – cabinetmakers, upholsterers, gilders – perpetuating the methods developed under the Second Empire.

This living transmission ensures the continuity of exceptional know-how threatened by massive industrialization.

Total Art: Yesterday and Today

The Second Empire heritage resonates powerfully in Garcia’s contemporary creation and that of his emulators.

Like Garnier supervised every detail of the Opera, Garcia conceives global environments where furniture, lighting, materials and colors contribute to a unique atmosphere.

This holistic approach, developed by 19th-century masters, finds natural echo in today’s projects.

The permanence of certain techniques – Boulle marquetry, gilding, art tapestry – testifies to the relevance of Second Empire innovations.

Noble materials, audacious polychromy, mastered eclecticism continue to inspire contemporary creators and collectors.

An Eternal Art de Vivre

The Napoleon III style transcends its historical dimension to embody a French art de vivre that endures and still inspires our contemporary creators.

Its essential lesson – reconciling tradition and modernity, elegance and comfort, refinement and accessibility – remains strikingly relevant in our era of mutations.

Contemporary lessons: At a time when design questions notions of sustainability and authenticity, the Second Empire offers the historical example of a creative era.

An era that knew how to innovate without denying its roots, create beauty without sacrificing utility, democratize luxury without debasing it.

This period teaches us that true elegance is born from the synthesis between heritage and creativity, between artisanal know-how and technical innovation.

Jacques Garcia brilliantly perpetuates this heritage by demonstrating the modernity of Napoleon III style and its capacity for adaptation to contemporary challenges.

His ability to extract the essence of this aesthetic – theatricality, mastered opulence, learned eclecticism – to reinvent it in a contemporary language testifies to the exceptional vitality of this tradition.

Hotel Costes, Château du Champ-de-Bataille and his numerous international creations establish Garcia as the worthy heir to Second Empire masters.

Second Empire Style Still in Vogue

The Napoleon III style remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration for all those who, today, work to reinvent French art de vivre in its universal dimension.

This creative continuity proves that French excellence in decorative arts remains an essential worldwide reference, perpetuated by visionary creators who know how to honor the past while inventing the future.

New Second Empire Style Furniture

For high-end new furniture in Napoleon III style, three French houses stand as absolute references: Henryot & Cie (Vosges), founded in 1867, master of buttoning and luxury upholstery for palaces, embassies and châteaux; Ateliers Allot (Brittany), active since 1812, renowned for its faithful re-editions in hand-carved solid wood, leaf gilding and personalized finishes; and Taillardat (Orléans), created in 1987, specialized in seats and furniture inspired by the 18th and 19th centuries with contemporary comfort and impeccable finishes. All three perpetuate exceptional know-how, combining historical fidelity, noble materials and entirely artisanal work.

Restoring Antique Second Empire Furniture

It is possible to restore Second Empire furniture in order to preserve its authenticity while restoring its brilliance and original function. This approach not only preserves a precious witness to the 19th century, but also extends its lifespan for daily or decorative use. Depending on the condition and nature of the furniture, the intervention may involve cabinetmaking — consolidation of the structure, re-gluing of assemblies, replacement of veneers, restoration of marquetries or inlays — or upholstery for seating, with restoration of garnishing and installation of fabrics faithful to the spirit of the era. Traditional finishes, such as gilding, tampon varnish or antique patina, perfect the ensemble, restoring the decorative richness and comfort characteristic of the Napoleon III style.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.