Streamline Moderne: The Golden Age of American Industrial Design (1930-1950)

New York, 1933. The “Century of Progress” World’s Fair in Chicago celebrated American technological progress at the heart of the Great Depression. While Europe sank into political tensions and Russian Constructivism faded under Stalin, America invented a radically new visual language: Streamline Moderne. This style, which would transform everything – from toasters to locomotives, from cinemas to automobiles – embodied American optimism and unshakeable faith in technological progress.

Far from Constructivist austerity or the geometric purity of De Stijl, Streamline Moderne celebrated aerodynamic curves, smooth surfaces, and horizontal lines that evoked speed. Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, Henry Dreyfuss, and Walter Dorwin Teague – the pioneers of American industrial design – created a style that reconciled modern aesthetics with mass production, accessible luxury with functional efficiency. This movement, often neglected in design history in favor of European modernism, nevertheless constituted the first true democratization of modern design.

What is Streamline Moderne

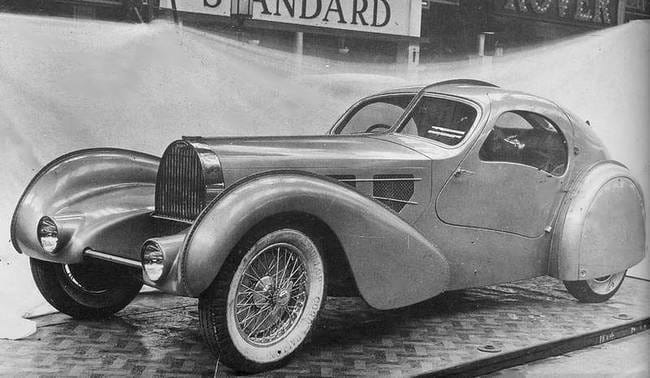

Streamline Moderne (or simply Streamline) is defined first by its formal vocabulary inspired by aerodynamics. Objects adopted streamlined forms, continuous curves, horizontal lines that suggested movement even when stationary. This aesthetic didn’t stem solely from technical considerations – few toasters need to be aerodynamic – but from a desire to symbolize modernity, speed, and progress.

This movement radically distinguished itself from its European contemporaries. Where the Bauhaus favored orthogonal geometry and functionalist rigor, Streamline cultivated the sensual curve and smooth surface. Where Parisian Art Deco celebrated geometric ornament and precious materials, American Streamline favored simplicity of forms and new industrial materials – aluminum, Bakelite, chrome steel.

Streamline was born in the 1930s, reached its peak in the 1940s, and began to decline in the 1950s with the emergence of international modernism. But unlike European avant-gardes, often elitist and theoretical, Streamline was profoundly popular and commercial. It transformed the American landscape – gas stations, diners, cinemas, train stations – and inscribed itself in the great history of design as the first manifestation of truly democratic design.

Historical & Cultural Context

1930s America experienced the worst economic crisis in its history. The Great Depression struck in 1929, unemployment exploded, industrial production collapsed. Paradoxically, it was in this crisis context that Streamline Moderne was born. Facing economic despair, America chose to believe in technological progress and consumption as engines of recovery.

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal (1933) mobilized the federal government to revive the economy. Major infrastructure projects – dams, roads, bridges – transformed the American landscape. The World’s Fairs in Chicago (1933-34) and New York (1939-40) celebrated “the world of tomorrow,” where technology would solve all problems. Norman Bel Geddes’s Futurama pavilion at the 1939 New York fair, which imagined America in 1960, attracted millions of fascinated visitors.

This period also saw the emergence of industrial design as a profession. Before the 1930s, design was the domain of engineers (for function) and decorative artists (for aesthetics). Streamline pioneers – Loewy, Bel Geddes, Dreyfuss, Teague – invented a new profession: creating manufactured objects that were simultaneously functional, beautiful, and sellable. They worked for America’s largest companies – General Electric, Coca-Cola, Pennsylvania Railroad, Studebaker – and transformed the appearance of American industrial production.

The technical context also favored Streamline’s emergence. New materials – aluminum, Bakelite, chrome, plexiglass – enabled the creation of smooth forms impossible with traditional materials. Progress in aerodynamics, first in aviation then in automobiles, captured popular imagination. Speed became a cultural obsession: aeronautical records, automobile races, express trains. Streamline visually translated this fascination.

Aesthetic Characteristics

Streamline aesthetics is immediately recognizable by its continuous horizontal lines, fluid curves, and smooth surfaces. Objects seemed sculpted by wind, profiled to cut through air. This aerodynamic pursuit applied even to stationary objects – refrigerators, radios, buildings – creating an aesthetic of immobile speed.

Formal Vocabulary

Teardrop curves structured compositions. The rear of objects tapered like a drop, suggesting forward movement. Horizontal chrome lines traversed surfaces, accentuating the impression of speed. Rounded corners replaced right angles, softening volumes.

Circular portholes – borrowed from ships and airplanes – punctuated facades and objects. These round windows, often associated with metallic surfaces, evoked the world of navigation and aviation. Horizontal colored bands created dynamic rhythm, often in red, cream, and chrome.

Minimal verticality also characterized the style. Unlike Art Deco skyscrapers that soared skyward, Streamline architecture favored horizontality, evoking ocean liners or fast trains rather than towers. This horizontal emphasis visually translated the conquest of American space, westward expansion, Route 66.

Materials and Colors

New industrial materials dominated the Streamline palette. Stainless or chrome steel brought brilliance and modernity. Aluminum allowed the creation of light curved forms. Bakelite, the first synthetic plastic, opened unprecedented possibilities for molding and color. Reinforced glass and vitrified tile clad commercial facades.

The chromatic palette favored bright and optimistic colors: cherry red, turquoise blue, cream, mint green. These hues, often combined with shiny chrome, created a joyful and modern effect. The contrast between reflective metallic surfaces and flat bright colors became the style’s signature.

Neon, perfected technology in the 1930s, transformed the nocturnal urban landscape. Luminous signs with cursive letters, often integrated into Streamline facades, became iconic of 1940s-50s America.

Creators & Key Figures

Raymond Loewy

Raymond Loewy (1893-1986), French emigrant to the United States in 1919, became America’s most famous industrial designer. His credo – “ugliness doesn’t sell” – summarized his philosophy: design isn’t a luxury but a commercial necessity. Loewy transformed the appearance of American industrial production.

His S-1 locomotive for Pennsylvania Railroad (1937), streamlined with continuous metallic cladding, became the icon of railway Streamline. His Studebaker Avanti (1962) pushed the limits of automotive aerodynamics. But Loewy also excelled in everyday objects: the Lucky Strike cigarette pack (1940), the Shell logo, the Coldspot refrigerator for Sears (1935). His design office employed hundreds and worked for America’s largest companies.

Norman Bel Geddes

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958) embodied Streamline’s most visionary dimension. A theater set designer turned industrial designer, he conceived utopian projects that fascinated the public. His Airliner Number 4 (1929), a giant plane for 600 passengers, his aquatic amphitheater, or his car of the future fed the American imagination.

But Bel Geddes especially excelled at staging progress. His Futurama pavilion at the 1939 New York Exhibition, sponsored by General Motors, showed America in 1960: multi-level highways, rational cities, aerodynamic transport. Seven million visitors discovered this optimistic vision of the future. Bel Geddes didn’t just design objects: he imagined systems – transportation, cities, lifestyles.

Henry Dreyfuss

Henry Dreyfuss (1904-1972) represented the most humanistic approach to industrial design. Obsessed with ergonomics before the term’s invention, he created objects adapted to users. His famous Joe and Josephine silhouettes, representing average man and woman with their measurements, guided all his projects.

His 20th Century Limited locomotive for New York Central Railroad (1938) rivaled Loewy’s S-1 in aerodynamic elegance. His Bell telephones (model 302 from 1937, model 500 from 1949) equipped millions of American homes. His John Deere tractor, Honeywell thermostat, Hoover vacuum demonstrated that utilitarian objects could be beautiful. Dreyfuss also published theoretical works like *Designing for People* (1955), helping found human-centered design.

Walter Dorwin Teague

Walter Dorwin Teague (1883-1960) brought a more refined and architectural dimension to Streamline. Trained as an illustrator, he converted to industrial design in the 1920s. His work for Eastman Kodak – notably the Baby Brownie cameras (1934) in colored Bakelite – democratized photography.

Teague also designed standardized Streamline Texaco gas stations, showcases for Corning Glass, exhibition stands. His Ford pavilion at the 1939 New York Exhibition complemented Bel Geddes’s, celebrating the automobile as a vector of American freedom. Later, he worked on the Boeing 707, applying Streamline principles to aeronautical design.

Russel Wright

Russel Wright (1904-1976) applied Streamline aesthetics to tableware and interior decoration. His American Modern dinnerware (1937), in ceramic with organic and curved forms, became the best-selling dinnerware in American history. His pastel colors – granite gray, sage green, coral – created a modern domestic palette.

Wright embodied Streamline’s most domestic and accessible aspect. His objects, sold in department stores at affordable prices, brought modern design into middle-class American homes. He also published *Guide to Easier Living* (1950), a domestic modernization manual that influenced millions of readers.

Representative Architecture and Design

Diners and Gas Stations

Diners – prefabricated restaurants in stainless steel – became temples of popular Streamline. Factory-built then transported to sites, these building-objects adopted the streamlined forms of train cars. Shiny metal facades, colored neons, circular portholes, vinyl banquettes: the diner embodied modern and mobile America.

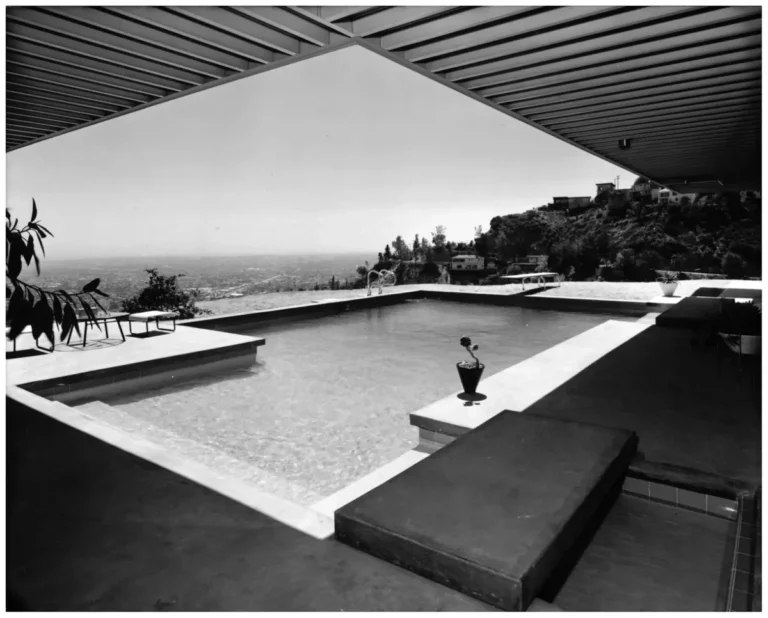

Streamline gas stations transformed the American roadside landscape. Texaco stations, standardized by Teague, with their cantilevered roofs and white tiled surfaces, became instantly recognizable. These commercial architectures, designed to be seen at automotive speed, favored simple forms, bright colors, and clear signage.

Cinemas and Theaters

Cinematographic architecture massively adopted Streamline. Thousands of Art Deco theaters were renovated in Streamline style in the 1930s-40s, others built from scratch. Curved facades, neons, streamlined marquees created an architecture of spectacle and escape.

The Colony Theater in New York (renovation), Avon Cinema in Providence, Castro Theater in San Francisco illustrated this entertainment architecture. Interiors shaped like ocean liners, indirect lighting, upholstered seats: Streamline cinema offered a total experience, an immobile voyage toward modernity.

Trains and Locomotives

Railway design constituted Streamline’s most spectacular application. Streamlined locomotives – Loewy’s S-1, Milwaukee Road’s Hiawatha, Burlington’s Zephyr – transformed the train into a symbol of speed and progress. These continuous metallic casings, often in stainless steel, masked mechanics under smooth, shiny surfaces.

Train interiors also adopted Streamline aesthetics: curved woodwork, chromes, indirect lighting, ergonomic seats. Dreyfuss’s 20th Century Limited offered modern, democratic luxury that contrasted with traditional European luxury. The train became mobile salon, rolling restaurant, traveling bedroom.

Domestic Objects

Streamline radically transformed everyday objects. Loewy’s Coldspot refrigerator (1935), with its soft curves and horizontal chrome handles, established the model of the modern “fridge.” Radios, often in colored Bakelite with circular dials, became domestic sculptures.

Toasters, mixers, vacuum cleaners adopted streamlined forms. This aerodynamicization of stationary objects might seem absurd – an iron doesn’t need to be streamlined – but it responded to symbolic logic: showing that these objects belonged to the modern era, the age of speed and progress.

Influence and Legacy

International Diffusion

Streamline remained essentially American but radiated internationally. Latin America, particularly Brazil and Argentina, massively adopted the style in the 1940s-50s. Pre-Castro Cuba was covered with Streamline buildings – cinemas, hotels, stores – that survive today in a paradoxically excellent state of preservation.

Europe observed Streamline with a mixture of fascination and mistrust. European modernists, more austere, criticized its commercial and populist aspect. But Streamline elements infiltrated: European automobile bodies rounded in the 1940s-50s, certain commercial buildings adopted curved facades and neons.

Decline and Nostalgia

Streamline began to decline in the 1950s with the emergence of international modernism – International Style, Scandinavian design. Streamline aesthetics, judged too commercial and superficial, gave way to a more rigorous and functionalist approach. Curves were replaced by straight lines, chrome by matte surfaces, bright colors by neutral tones.

But paradoxically, by the 1970s, Streamline experienced a nostalgic resurgence. Diners, threatened with destruction, were classified as historic monuments. Collectors fought over Bakelite radios and Streamline furniture. This nostalgia reflected the loss of 1930s-50s technological optimism, regret for an era when America believed in progress.

Influence on Contemporary Design

Streamline heritage irrigates contemporary design underground. Current automotive aerodynamics, today motivated by energy efficiency, formally takes up Streamline vocabulary. Apple products, particularly the first colored iMacs (1998), explicitly cited the aesthetics of 1940s Bakelite radios.

Designers among the great current names like Marc Newson or Karim Rashid claim Streamline’s influence in their organic forms and bright colors. Contemporary transport design – TGV, airplanes, concept cars – prolongs the aerodynamic research initiated by Streamline.

Retro-futurism, an aesthetic current that imagines the future as the 1930s-50s conceived it, draws directly from Streamline. Films like *Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow* (2004), video games like the *Fallout* series, retro graphic design: Streamline imagery continues to nourish contemporary visual culture.

Current Market and Collections

Valuation and Market

The Streamline market has experienced constant valorization since the 1990s. Miniature locomotives and scale models of Streamline trains reach high prices. Period furniture – tables, chairs, desks in chrome tube and Bakelite – trades between a few hundred and several thousand euros depending on creators.

Domestic objects – radios, clocks, fans – constitute an active market. An Emerson Bakelite radio, a Westinghouse chrome fan, a Waring mixer can reach several hundred euros in good condition. Original neon signs from diners or gas stations are particularly sought after.

Drawings and renderings by great designers – Loewy, Bel Geddes, Dreyfuss – sell at substantial prices in specialized auctions. These documents, often airbrushed with photo-realistic rendering, testify to the creative process and the importance of presentation in industrial design.

Preservation and Institutions

The Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art hold important Streamline collections. The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn (Michigan) presents locomotives, automobiles, and domestic objects in complete historical context.

Preserving Streamline architecture poses specific challenges. Numerous diners, cinemas, and gas stations were demolished in the 1960s-80s. Survivors, often classified, require costly restorations. Organizations like the Society for Commercial Archeology advocate for their preservation, recognizing their importance in American heritage.

Conclusion

Streamline Moderne embodied American optimism facing the 1930s crisis, faith in technological progress, and the democratization of modern design. By applying aerodynamic principles to all objects of daily life, this movement transformed the American visual landscape and invented industrial design as a profession.

This approach radically distinguished Streamline from contemporary European movements. Where Russian Constructivism put design in service of proletarian revolution, Streamline put it in service of capitalist consumption. Where De Stijl sought universal harmony in pure abstraction, Streamline aimed for commercial efficiency in the seduction of forms. The Bauhaus attempted to reconcile art and industry in a humanistic perspective, Streamline frankly assumed its commercial dimension.

Yet beneath its superficial and commercial appearance, Streamline carried genuine innovation: the democratization of modern design. Loewy, Dreyfuss and their peers didn’t create for a cultivated elite but for the mass market. Their refrigerators, radios, trains touched millions of Americans. Modern design entered ordinary homes, transformed daily gestures, modified urban and roadside landscapes.

Streamline’s legacy remains ambivalent. On one hand, it proved that design could be popular without being vulgar, commercial without being cynical, optimistic without being naive. On the other, it perhaps too closely linked design and consumption, aesthetics and marketing, beauty and profit. This tension still irrigates contemporary design.

Current creators like Marc Newson, Ross Lovegrove, or Karim Rashid prolong the search for organic and aerodynamic forms initiated by Streamline. Automotive design, today motivated by energy efficiency rather than symbolism, paradoxically rediscovers 1930s streamline forms. Product design retains this streamline lesson: objects must not only function but communicate their modernity.

A century after its birth, Streamline fascinates through its assumed optimism and faith in progress. In a contemporary world marked by climate and technological anxiety, this aesthetic of joyful speed and radiant future seems both naive and touching. Yet its message resonates: design can make the ordinary extraordinary, transform banality into modernity, and democratize industrial beauty.

This capacity to combine popular accessibility and aesthetic ambition, commercial efficiency and formal innovation makes Streamline a perpetually relevant movement. Its legacy reminds us that design need not choose between aesthetic elitism and commercial populism, that it can simultaneously serve art, industry, and the public. Even if the technological optimism that saw it born belongs to another era, the streamline requirement – creating beautiful, functional, and accessible objects – remains an inspiration for those who believe in design’s democratic power.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.