Radical Design: Italian Anti-Design (1960–1975)

Florence, 1966. A group of young Italian architects found Archizoom Associati and begin producing provocative projects that question every certainty of modern design. While Good Design champions rationality and the Ulm School systematizes methodology, an Italian avant-garde radically rejects functionalism. Radical Design emerges—oppositional, conceptual, provocative. This movement, which dominates Italy from 1966 to 1975, does not aim to create beautiful objects but to critique consumer society, question ways of living, and explore alternative utopias.

Unlike classical Italian Design that celebrates industrial elegance, Radical Design embraces provocative ugliness, embraced kitsch, and conceptual uselessness. Ettore Sottsass, Gaetano Pesce, the groups Archizoom, Superstudio, UFO, Gruppo Strum: these creators do not seek to improve design but to subvert it—turning objects into political manifestos and using architecture as social critique. This radicality sets the stage for the postmodern explosion of the 1980s and profoundly shapes contemporary critical design.

What Is Radical Design

Radical Design refers to an Italian avant-garde (circa 1966–1975) that rejects modernist functionalism to explore conceptual, critical, and experimental design. “Radical” does not mean extremist; it goes back to the Latin radix (root): returning to fundamentals, questioning assumptions, and rethinking the role of design in society.

This approach overturns the certainties of modern design. Where the Bauhaus asserts “form follows function,” Radical Design claims that form can challenge function. Where Mid-Century Modern celebrates consumer prosperity, Radical Design denounces that society of consumption. Where Ulm develops scientific methods, Radical Design values the irrational, the poetic, the absurd.

The movement emerges amid the widespread unrest of the 1960s—May ’68 in France, student movements in Germany and Italy, American counterculture. Everywhere, young people question the established order. Radical designers apply this critique to design itself: why create beautiful objects for a society they deem alienating? How can design contribute to social transformation?

This radicality enters the grand history of design as a moment of critical reflexivity. For the first time, designers systematically question their own practice, using design as an instrument of critique rather than production. This anticipates today’s critical design (Anthony Dunne, Fiona Raby).

Historical & Cultural Context

Italy in the 1960s undergoes spectacular transformations. The economic miracle rapidly enriches the country, creating a mass consumer society. But prosperity also generates alienation, conformism, and artificiality. Italian youth—especially students and young architects—reject this model.

The political climate radicalizes positions. The powerful Italian Communist Party (PCI) provides a Marxist framework for social critique. The 1968 student movements occupy universities and challenge authoritarianism. The Years of Lead (anni di piombo, 1969–1988) see far-left and far-right terrorism tear Italy apart. Radical Design emerges within this tense, feverish atmosphere.

Radical architecture precedes product design. Florentine groups—Archizoom, Superstudio, UFO, Gruppo 9999—begin by critiquing modern architecture as serving capitalism. Their utopian projects—continuous cities, continuous monuments, nomadic habitats—imagine alternative ways of living. This conceptual approach gradually extends to objects.

The magazine Casabella, directed by Alessandro Mendini from 1970, becomes a platform for the movement. Exhibitions—Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at MoMA (1972) gives Radical Design international recognition—spread the ideas. The Milan Triennials host provocative installations.

Pop culture matters too. Underground comics, psychedelic rock, hippie culture—all inspire the radicals. Unlike modernist purism, they embrace popular culture, kitsch, and blazing color. This openness foreshadows postmodernism.

Groups & Key Figures

Archizoom Associati (1966–1974)

Archizoom, founded in Florence by Andrea Branzi, Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi, produce some of the most provocative projects. Their No-Stop City (1969–1972) imagines an endless factory-city: a homogeneous grid without “architecture,” a pure air-conditioned infrastructure. This dystopian utopia critiques both modern urbanism and industrial capitalism.

Their furniture—Mies chair (1969), a kitsch parody of Mies van der Rohe in printed laminate, or Superonda (1966), an undulating sofa-sculpture—mixes pop irony and formal sophistication. Archizoom demonstrate that design can be both a theoretical critique and a seductive object.

Their approach deeply influences architectural thought: that architecture can critique society through unbuildable projects; that drawing and the manifesto are legitimate practices—all flow from Archizoom.

Superstudio (1966–1978)

Superstudio, also founded in Florence by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, develop a more ascetic approach. Their Architecture Histograms (1969–1972)—photomontages of infinite grids covering landscapes—imagine a world without architecture, reduced to minimal structure.

Their Continuous Monument (1969)—a gridded structure spanning deserts, oceans, cities—proposes a total architecture that paradoxically abolishes architecture. This radical critique of modern rationalism through hyper-rationalization shapes conceptual architecture.

Their Quaderna furniture (1970, Zanotta)—tables covered with laminate printed with a black grid—materializes their obsession with the grid. Beautiful despite its critical intent, it illustrates Radical Design’s ambiguity: can one critique consumption while producing desirable objects?

Ettore Sottsass

Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007), already an established designer at Olivetti, radicalizes his approach in the 1960s. His series of erotic ceramics (1963)—brightly colored phallic and organic forms—shocks the design scene. His Mobili Grigi (1970)—massive gray-laminate cabinets—critique functional furniture by exaggeration.

Sottsass also writes extensively. His texts in Casabella and his own publications develop a philosophy of design as language, a system of signs rather than mere problem-solving. This semiotic approach influences the entire movement.

His trip to India (1961) leaves a deep mark: vernacular architecture, saturated colors, Eastern spirituality—all nourish his critique of Western rationality and enrich Radical Design.

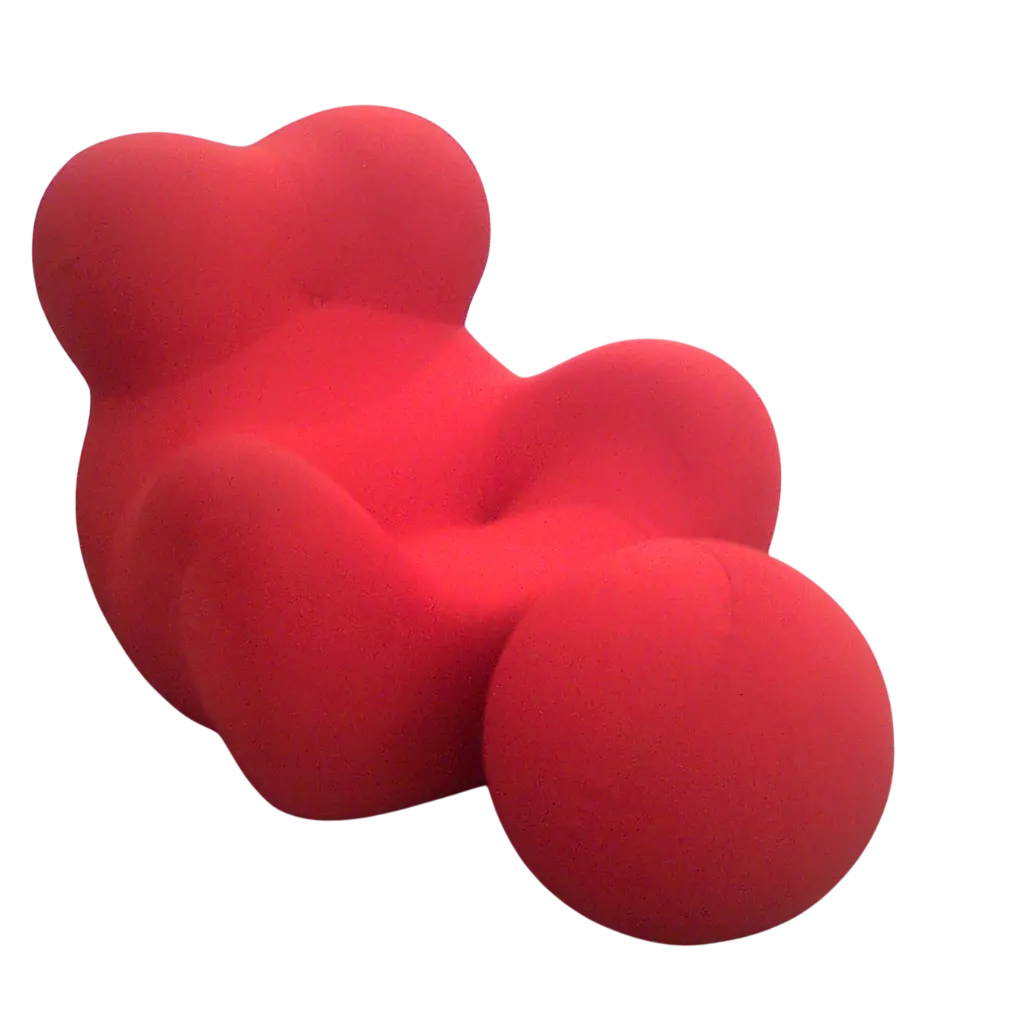

Gaetano Pesce

Gaetano Pesce (born 1939) embodies Radical Design’s experimental dimension. His UP5-UP6 “Donna” armchair (1969, B&B Italia)—a compressed, vacuum-packed female form that expands when opened—critiques the oppression of women while remaining an industrial design object.

(Photo: Pava — CC BY-SA 3.0 IT)

His experiments with polyester resin—a material enabling unpredictable organic forms—generate unique objects despite industrial production. This tension between artisanal uniqueness and industrial reproduction questions the status of the design object.

Pesce also works in architecture, notably his Organic Building apartments in Osaka (1993)—each unit different—materializing his conviction that modern standardization alienates.

Secondary Groups

UFO (1967–1978) explore the performative dimension. Their Urboeffimeri—temporary inflatable structures—imagine an ephemeral, playful, participatory architecture. Gruppo Strum develops participatory architecture projects involving residents in the design process. Gruppo 9999 organize happenings and performances questioning the architect’s role.

Signature Works & Concepts

The Sacco Armchair (1968)

The Sacco by Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini, and Franco Teodoro (Zanotta, 1968) becomes an icon of Radical Design. A vinyl sack filled with polystyrene beads, with no fixed structure, molding to the body: it rejects the entire history of furniture. No legs, no armrests, no defined shape.

This negation of conventions seduces immediately. Sacco embodies the counterculture: informal, relaxed, anti-authoritarian. Its commercial success (millions sold) illustrates the radical paradox: a protest object becomes a mass-market product.

Inflatable Furniture

Inflatable furniture—armchairs and sofas in transparent plastic—fascinates the radicals. Lightweight, portable, ephemeral, colorful: it embodies a nomadic, playful, anti-conventional lifestyle. Its transparency also critiques the opacity of traditional furniture.

But fragility and relative discomfort limit real-world use. It works better as a manifesto than as everyday furniture—exactly what the radicals seek: turning design into an act of communication rather than the production of utilities.

Utopian Architectures

Unbuildable architectural projects are a major contribution. No-Stop City, Continuous Monument, nomadic cities—all imagine radically different ways of living. These projects aim not at realization but at critique: pushing modern urbanism to its limits to reveal its absurdities.

This approach—using the project as a theoretical tool rather than a construction plan—profoundly influences conceptual architecture. Groups like OMA/Rem Koolhaas and MVRDV inherit this method.

“Anti-Functional” Design

Some radical creations are deliberately useless or uncomfortable. Wobbly chairs, blinding lamps, absurd objects: all critique the functionalist obsession. If design serves only function, what happens when function is denied?

This provocative stance opens fertile questions. Do objects have roles beyond utility? Can they communicate, critique, question? Radical Design answers yes—shaping contemporary critical design.

Influence & Legacy

Memphis & Postmodernism

The Memphis movement (1981–1988), founded by Sottsass, extends and commercializes Radical Design. Colorful geometric forms, kitschy printed laminates, pop ornament: Memphis adopts the radical vocabulary but applies it to producible, sellable objects. This paradoxical commercialization confirms the movement’s influence.

Postmodern architecture and design in the 1980s inherit massively from Radical Design. The rejection of functionalism, the valorization of décor, irony, eclecticism—all stem from the Italian radicals. Michael Graves, Robert Venturi, Charles Jencks acknowledge this debt.

Contemporary Critical Design

Contemporary critical/speculative design—Anthony Dunne & Fiona Raby, Noam Toran, Superflux—directly inherits the radical approach: making objects that question rather than serve; using design as a tool for critical reflection on technology and society.

Projects like Critical Design (Dunne & Raby), Speculative Everything, and design fictions apply the radical methodology to contemporary issues—biotech, surveillance, artificial intelligence. Radical Design proved this approach both legitimate and fruitful.

Influence on Design Thinking

Beyond form, Radical Design transforms the very conception of design. The idea that a designer can be a social critic, theorist, provocateur—not only a problem-solver or maker of beautiful things—now structures the discipline.

Design schools teach critical design, ask students to challenge assumptions, and encourage conceptual projects. This reflexive dimension—absent from modernism—flows directly from Radical Design.

Limits & Critiques

Radical Design also faces legitimate critiques. Its intellectual elitism—projects legible only to insiders—limits its impact. Its rapid commercial co-optation questions critical effectiveness. Its sexism (few women in radical circles, often sexist objects) is problematic in retrospect.

The question of political effectiveness remains open. Did radical projects transform society, or merely create an aesthetic niche for a cultivated avant-garde? The tension between revolutionary ambition and market absorption runs through every critical movement.

Market & Collecting

The market for Radical Design has surged since the 2000s. Memphis pieces—sideboards, lamps, shelving—reach tens of thousands of euros. Rarer Archizoom or Superstudio works exceed €50,000 for significant sets.

The Sacco, still produced by Zanotta, remains accessible (around €300), proof of its lasting commercial success. UP pieces by Gaetano Pesce, reissued by B&B Italia, sell between €2,000 and €5,000.

Graphic archives—drawings and photomontages by Archizoom and Superstudio—attract collectors and museums. The Centre Pompidou, MoMA, and the Vitra Design Museum hold major collections, recognizing the movement’s historical significance.

Conclusion

Radical Design (1966–1975) marks the moment when Italian design radically questions its own foundations. By rejecting functionalism, critiquing consumer society, and using design as an instrument of social critique, the movement permanently reshapes how design is conceived.

This subversive stance sets the movement apart from its contemporaries. Where Good Design defines criteria of quality, Radical Design contests the very idea of “good design.” Where the Ulm School systematizes method, Radical Design values intuition and the irrational. Where classic Italian Design celebrates elegance, Radical Design embraces provocation.

The legacy of Radical Design remains extraordinarily alive. The movement showed that design can be critical, conceptual, political—not merely problem-solving or object-making. This legitimization of critical design profoundly shapes contemporary practice.

Among today’s leading names, creators like Anthony Dunne, Fiona Raby, Noam Toran, and Superflux explicitly extend the radical approach to 21st-century issues. Their speculative projects on biotechnology, surveillance, and climate change use exactly the method developed by the Italian radicals.

Half a century after its emergence, Radical Design fascinates for its intellectual audacity and enduring critical relevance. In a world where design is often reduced to a commercial style or to technical problem-solving, the radical legacy reminds us that design can and should question, provoke, and imagine alternatives. Its message resonates powerfully amid today’s climatic, social, and technological crises that demand precisely this capacity to think radically differently.

This conviction—that design carries a critical responsibility not only to serve the existing system but to question it, imagine alternative futures, and provoke reflection—keeps Radical Design perpetually current. Its legacy reminds us that design is never neutral, that making objects is always a political act, and that creative imagination can be a tool for social transformation. Even if the radicals’ revolutionary utopia proved naïve, their fundamental demand—that design serve human emancipation rather than commercial profit—remains a precious inspiration for anyone who refuses to reduce design to its mercantile dimension.

Resources

Design Fundamentals

The Big Design History

From baroque salons to the radical lines of the 20th century, this timeline highlights the aesthetic revolutions that have shaped our everyday environment.

Read the page “The Big Design History”Hart Dictionary of Great Design Names

This dictionary lists the great names of design and decoration in alphabetical order. Discover the creators who have shaped contemporary art de vivre.

Read the page “Hart Dictionary of Great Design Names”History of Classic French & European Decorative Styles

Empire, Regency, Louis XV, Art Deco… This guide summarizes the decorative codes of each major European style.

Read the page “History of Classic French & European Decorative Styles”Hart Design Glossary A–Z

Sabre leg, patina, trimmings, caning… This glossary explains the technical and stylistic terms commonly used in the world of design and decoration.

Read the page “Hart Design Glossary A–Z”

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.