Bauhaus: The German School That Shaped Modern Design

1. What is Bauhaus?

Bauhaus Definition

Born in Germany in the aftermath of World War I, the Bauhaus marked a decisive turning point in the history of decorative arts and design. More than just an art school, this revolutionary movement redefined the relationship between artistic creation and industrial production, laying the foundations for an aesthetic that still transcends disciplinary boundaries today.

Founded in 1919 in Weimar by Walter Gropius, the movement then developed in Dessau and later in Berlin, until its closure in 1933 under pressure from the Nazi regime. During these fourteen years of existence, the school trained a generation of artists, architects, and designers who would revolutionize global creation. Its influence extends far beyond the German framework to irrigate the entirety of Western modernity.

Why this style matters today: The Bauhaus laid the foundations of modern design by advocating the synthesis between art, craft, and industry, and continues to influence contemporary architecture, furniture, and graphic design. Its motto “Form follows function” still resonates in our interiors, cities, and everyday objects, making the Bauhaus one of the most enduring and universal movements in design history.

The Bauhaus School

The Bauhaus school, founded in 1919 in Weimar by Walter Gropius, was an artistic and pedagogical revolution that unified applied arts, fine arts, architecture, and crafts in a utopian vision of total art. This holistic approach radically broke with traditional Fine Arts education, privileging experimentation, collaborative work, and the alliance between theory and practice. The school moved to Dessau in 1925 where Gropius designed the famous building – an icon of the international style, with glass facades, concrete and steel, open and functional, perfect embodiment of the ideals it professed.

The Beginnings of Bauhaus: Weimar (1919–1925)

In this city steeped in German cultural history, the nascent school had to contend with a conservative environment unfavorable to its experiments. Gropius nevertheless developed the theoretical foundations of the movement: abolition of the hierarchy between “major” and “minor” arts, training of versatile artisan-creators, and close collaboration with industry. The first workshops – metallurgy, weaving, carpentry, photography – took shape in makeshift premises, but the creative energy was palpable.

Dessau (1925-1932)

Designed by Walter Gropius in 1926, this emblematic building translates the movement’s principles into architecture. Its pure geometric volumes, entirely glazed curtain walls, and open-plan spaces announce international modern architecture. Here, the Bauhaus reached its creative maturity: workshops produced their masterpieces, the “masters” developed their most accomplished theories, and the school radiated across Europe. This Dessau period remains the golden age of the movement, when social utopia and aesthetic excellence converged harmoniously.

2. Historical & Cultural Context

Political, social, artistic framework: In a Germany wounded by war, confronted with the upheavals of the Weimar Republic and the social tensions of galloping industrialization, the Bauhaus sought to rebuild a new world by abolishing the boundaries between fine arts and applied arts. This era of profound mutation – political revolutions, nascent female emancipation, massive urbanization – called for an aesthetic refoundation capable of reconciling art with the daily life of the greatest number.

Innovations, influences: The movement drew inspiration from Russian constructivism with its social approach to art, the Arts & Crafts movement and its artisanal values, and nascent modernism with its faith in technical progress. It integrated industrial rationality and functionality as central values, while drawing from pictorial avant-gardes (expressionism, abstraction) to nourish its formal vocabulary. This unique synthesis between industrial pragmatism and radical plastic research forged the originality of the Bauhaus.

3. Aesthetic Characteristics

- Lines, forms, colors: Simple geometric forms (square, circle, triangle), straight lines, flat primary colors (red, blue, yellow) complemented by black and white. This restricted palette, inspired by the theories of Kandinsky and Klee, aims for universality and communicative clarity.

- Patterns & materials: Privileged use of chrome metal, industrial glass and raw concrete; systematic elimination of superfluous ornaments in favor of the intrinsic beauty of materials and the accuracy of proportions. New synthetic materials are explored with enthusiasm.

- Techniques: Standardization of elements, mass production adapted to economic imperatives, revolutionary fusion between conceptual design and industrial process. The Bauhaus object anticipates its reproducibility and democratizes access to beautiful design.

4. Creators & Key Figures

Founder and Teachers

Walter Gropius

Founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius (1883-1969) advocated the fusion between art and industry, and initiated the school’s innovative pedagogical program. An architect by training, he developed a social vision of design where functional beauty should benefit the greatest number. His charismatic leadership and theoretical manifestos permanently structured the movement’s identity. Emigrated to the United States in 1937, he would propagate Bauhaus ideals in American architectural education.

Paul Klee

Swiss painter and pedagogue (1879-1940), he taught the theory of form and color at the Bauhaus from 1920 to 1931, profoundly influencing the school’s aesthetic vision. His methodical courses on chromatic interactions and compositional dynamics nourished both painting and object design. His poetic and scientific approach to art tempered the sometimes too industrial orientation of the movement with an indispensable lyrical sensitivity.

Wassily Kandinsky

Theorist of abstraction, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) developed a spiritual approach to forms and colors that considerably enriched the Bauhaus’s aesthetic reflection. His theoretical works, notably “Point and Line to Plane,” codified a universal plastic language that influenced all the school’s workshops. His mysticism tempered by Germanic rigor created an original synthesis between emotion and rationality.

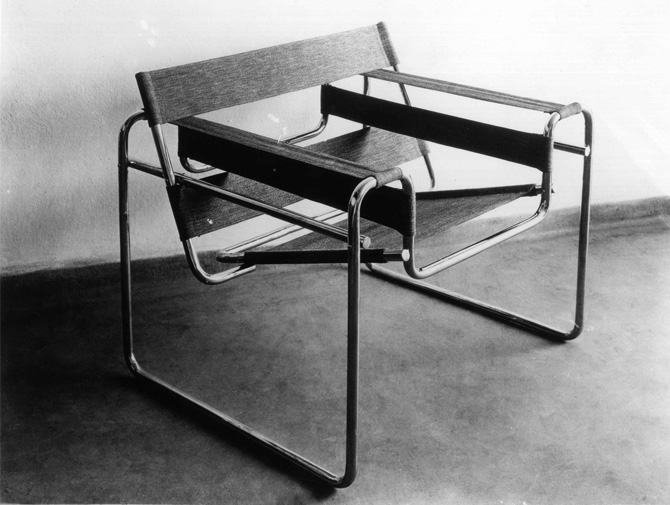

Marcel Breuer

Hungarian designer and architect (1902-1981), he created the famous Wassily chair and experimented with the revolutionary use of steel tubing in furniture. A former student who became a master, Breuer perfectly embodied the Bauhaus philosophy: combining technical innovation, economy of means, and formal elegance. His tubular furniture, inspired by bicycle handlebars, revolutionized the furniture industry and democratized modern design.

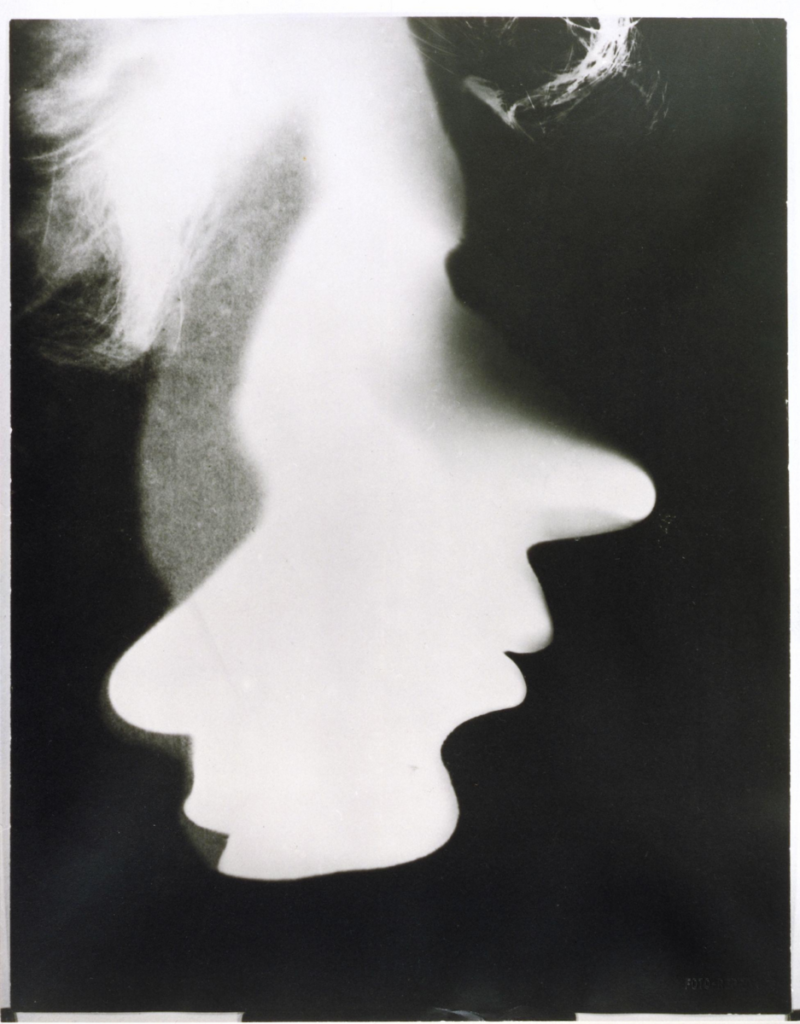

László Moholy-Nagy

Hungarian artist and photographer (1895-1946), he introduced photography, typography, and graphic design into the Bauhaus program, considerably expanding its field of action. Pioneer of the “New Vision” photography, he developed experimental techniques (photograms, overexposures, unexpected framings) that revolutionized modern visual communication. His multimedia approach anticipated contemporary creative practices.

Bauhaus Students

Beyond the famous masters, it was an entire generation of students who forged the soul of the Bauhaus. Coming from all over Europe, they experimented in the workshops according to a revolutionary pedagogy mixing theoretical courses and intensive practice. This cosmopolitan and passionate youth created exceptional creative emulation, where the boundaries between teachers and students blurred in a common quest. Many would in turn become major figures in international design.

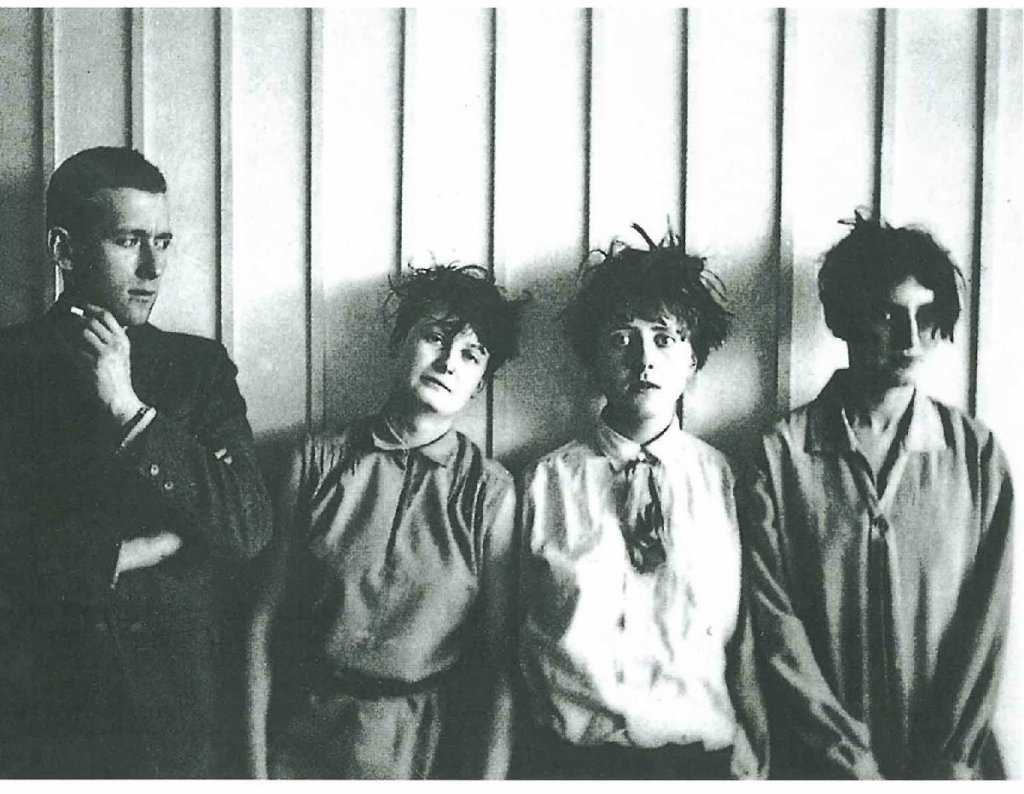

Women of the Bauhaus: A Long-Obscured Legacy

Behind the canonical images of Gropius, Breuer, or Mies van der Rohe, a generation of women left their mark on Bauhaus history. Relegated at the time to so-called “feminine” workshops (weaving, textile, embroidery), they were nevertheless the true pioneers of entire disciplines. Despite the prejudices of their time that limited their access to metal or architecture workshops, these creators managed to impose their vision and revolutionize applied arts. Their contribution, long minimized, is today the subject of a major historical reevaluation.

Anni Albers (1899–1994)

Major figure of modern textiles, she transformed weaving into autonomous art, far surpassing its traditional artisanal status. Her geometric patterns, both rigorous and sensitive, anticipated contemporary textile design and explored the expressive potential of industrial fibers. Her influence extended to the United States when she founded, with her husband Josef Albers, the experimental school of Black Mountain College, a laboratory of American artistic avant-garde. Her works, now preserved in the greatest museums, testify to a constant search between functionality and poetry.

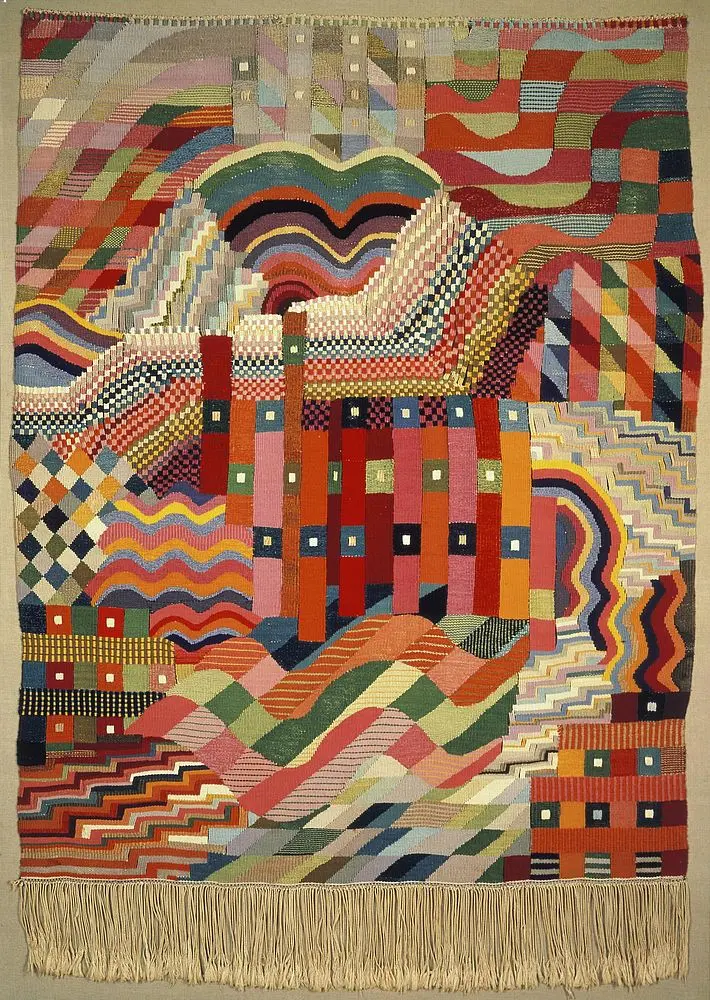

Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983)

First and only female master at the Bauhaus, director of the weaving workshop from 1926 to 1931. She imposed a resolutely modern approach to textiles, integrating synthetic fibers and abstract patterns in production that was both artistic and industrial. Her technical innovations – unprecedented material blends, new textures, dyeing processes – revolutionized the European textile industry. Victim of anti-Semitic persecution, she emigrated to Switzerland where she continued her career, permanently influencing Swiss textile design.

Marianne Brandt (1893–1983)

Goldsmith and industrial designer, she revolutionized metal arts by establishing herself in a traditionally masculine domain. Her teapots, lamps, and everyday objects combined formal radicality and functional elegance, creating an aesthetic vocabulary still relevant today. Her prototypes, designed for mass production, anticipated contemporary industrial design. After the Bauhaus, she worked for various German manufacturers, contributing to spreading modern aesthetics in European industry.

Lucia Moholy (1894–1989)

Photographer and chronicler of the Bauhaus, she immortalized the school and its protagonists in shots that became iconic. Her portraits, architectural views, and still lifes of objects constitute today the visual memory of the movement. Perfectly mastering laboratory techniques, she developed a refined photographic style, in perfect harmony with Bauhaus aesthetics. Her images, widely distributed in period publications, contributed to forging the school’s international reputation.

These women, long overshadowed by their male colleagues, are today celebrated in museums and auction houses. Their textile, photographic, and metal works are highly sought after, embodying the functional and sensitive modernity of the Bauhaus. This belated but well-deserved recognition reveals the essential contribution of feminine genius to one of the most influential movements of the 20th century.

5. Furniture & Representative Objects

Bauhaus Seating – Chronology of Creations

F51 Armchair by Walter Gropius (1920)

Designed in 1920 by the Bauhaus founder himself, the F51 armchair embodies the transition between traditional craftsmanship and nascent modern aesthetics. Gropius developed a refined geometry in solid wood, precursor to the formal research that would define the movement. This rare piece, witness to the master’s first experiments, reveals his progressive approach toward industrial standardization while preserving the nobility of artisanal work. Its angular structure and mathematical proportions already announce the formal vocabulary that would revolutionize 20th-century design.

Current edition: Not officially reissued – Collector’s piece only available in antiques and auction sales.

Wassily Chair by Marcel Breuer (1925-1926)

Absolute icon of modern furniture, the Wassily chair (1925-1926) combines tubular chrome steel structure and leather straps in a revolutionary synthesis between technical innovation and formal elegance. Inspired by Breuer’s bicycle handlebars, this creation bears the name of painter Kandinsky and perfectly embodies the Bauhaus philosophy: beauty, functionality, and industrial reproducibility. Its immediate commercial success confirmed the relevance of the Bauhaus approach to democratizing quality design.

Current edition: Knoll International (official license) – Price: €2,800 to €4,200 depending on finishes (natural, black or cognac leather). Also available from Gavina/Tecta in Germany.

Cantilever Chair by Mart Stam (1926)

First chair without rear legs in design history, this technical and formal prowess revolutionized the approach to furniture. Mart Stam invented the principle of cantilever in tubular steel, exploiting the natural elasticity of the material to create a seat of striking visual lightness while offering optimal comfort thanks to the spring effect. This fundamental innovation immediately inspired his colleagues Breuer and Mies van der Rohe.

Current edition: Thonet (model S33) – Price: €1,800 to €2,400 depending on finishes. Also at Tecta (model D4) around €2,200.

Cesca Chair by Marcel Breuer (1928)

Perfect synthesis between structural modernity and artisanal tradition, the Cesca chair (1928) combines Breuer’s revolutionary chrome steel tubing with traditional caning, creating a fruitful dialogue between innovation and heritage. This unexpected alliance demonstrates the Bauhaus’s ability to reinterpret ancestral know-how in contemporary language, paving the way for a tempered modernism that still influences current design. Its name pays homage to Francesca, Breuer’s adopted daughter.

Current edition: Knoll International (Cesca model) – Price: €1,200 to €1,800 depending on finishes. Thonet also offers its version (S32/S64) between €1,400 and €2,000.

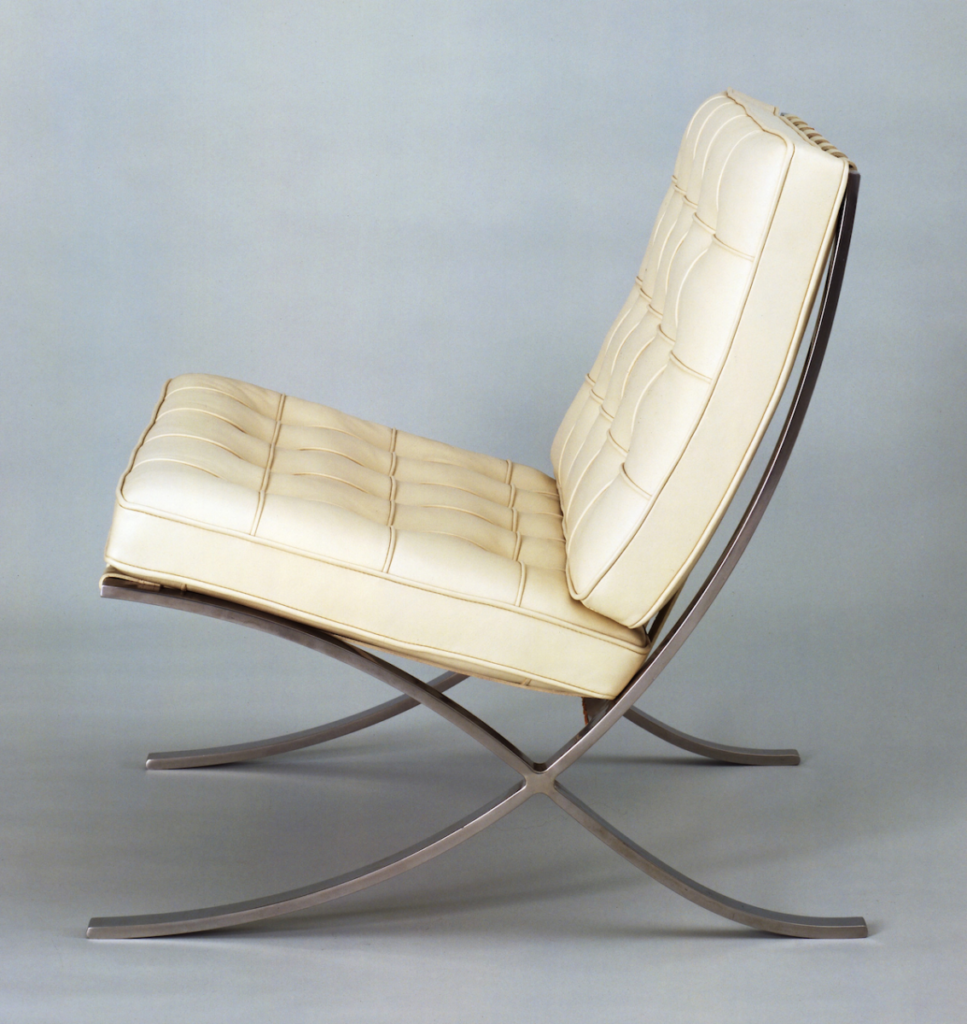

Barcelona Chair by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1929)

Created for the German pavilion at the Barcelona Universal Exhibition, this armchair crystallizes the excellence of Bauhaus design in its most refined phase. Mies van der Rohe deployed his maxim “Less is more” in geometry of absolute purity, where polished steel and quilted leather achieve perfect harmony. More than a seat, it is an aesthetic manifesto that still influences the elite of international furniture design today. Its artisanal manufacturing requires more than 100 manual operations.

Current edition: Knoll International (exclusive worldwide license) – Price: €7,500 to €12,000 depending on leather type (standard, premium or vintage). Each piece is numbered and certified.

Bauhaus Table Lamps (Wilhelm Wagenfeld)

Minimalist and functional objects par excellence, Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s luminaires combine industrial frosted glass and chrome metal in an exemplary economy of means. These creations, which have become timeless classics of lighting design, illustrate the Bauhaus’s ability to transform utilitarian objects into accessible works of art. Their mass production democratized access to quality lighting, materializing the movement’s social utopia.

Textiles by Gunta Stölzl

Director of the weaving workshop, Gunta Stölzl developed geometric patterns in vibrant colors, perfectly adapted to industrial production. Her creations revolutionized the approach to textiles by integrating natural and synthetic fibers in compositions of striking modernity.

These textile works, true chromatic and textural laboratories, anticipated contemporary developments in surface design and avant-garde fashion.

Important note: As Bauhaus creations are in the public domain, many manufacturers offer unauthorized “reissues” at lower prices. Only the publishers mentioned above hold official licenses and guarantee fidelity to original plans as well as the quality of materials and finishes.

6. Heritage & Reinterpretations

Influence on Subsequent Styles

The Bauhaus directly inspired the International Style in architecture, American modernism of the 1940s-1960s, and the minimalist aesthetic that runs throughout the 20th century. Its principles irrigated the Ulm School in post-war Germany, Scandinavian design with its functionalist values, and even the postmodern movement which, while opposing it, defined itself in relation to its heritage. From Frank Lloyd Wright to Tadao Ando, from Dieter Rams to Jonathan Ive, the Bauhaus lineage crosses creative generations.

Contemporary Reappropriations

Its principles of sobriety and functionality still nourish Scandinavian design with its values of simplicity and authenticity, Japanese minimalism and its refined aesthetic, and current sustainable architecture that advocates economy of means and environmental justice. In digital, interface design draws directly from Bauhaus theories on communicative clarity and functional efficiency. Even contemporary art draws from this formal heritage to question the relationships between art and society.

7. Market Value & Current Market

New Purchase

Contemporary reissues, produced under license by prestigious manufacturers like Knoll International, Tecnolumen or Thonet, maintain Bauhaus technical excellence while adapting it to current standards. A Wassily chair costs between €2,500 and €4,000, a Wagenfeld lamp around €400 to €800, while a Barcelona armchair reaches €6,000 to €8,000. These prices reflect the impeccable quality of materials and the complexity of manufacturing processes, justifying the investment in these timeless icons.

Second Hand

The market for original Bauhaus pieces is experiencing real speculative euphoria, reflecting the growing museum recognition of the movement. A period Breuer chair can exceed €20,000, an original Barcelona armchair easily reaches €50,000, while Stölzl textiles are traded at auctions for several tens of thousands of euros. Wagenfeld luminaires, more accessible, start around €3,000. This price surge testifies to the growing rarity and collectors’ appetite for these witnesses of a revolutionary era.

In Summary

The Bauhaus embodies the revolutionary fusion between art, design, and industry, with a geometric, functional, and universal aesthetic that transcends eras and borders. In just fourteen years of existence, this movement redefined the codes of modern creation and laid the foundations for a visual culture still vibrant today.

Why the Bauhaus remains essential: Because it laid the foundations of modern design and continues to inspire contemporary creation in all its aspects – from furniture to architecture, from graphic design to digital – the Bauhaus remains an unsurpassable pillar of global visual culture. Its utopia of democratic and functional art resonates with particular acuity in the era of contemporary environmental and social challenges, confirming the visionary accuracy of its founding intuitions.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.