Ulm school: The methodological revolution of design (1953-1968)

Ulm, Germany, 1953. On a hill overlooking the city, Max Bill inaugurates the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG Ulm), a design school that aims to reconnect with the legacy of the Bauhaus closed by the Nazis in 1933. But Ulm will not be a simple resurrection: it will radicalize the rationalist approach, develop a scientific methodology of design, and anticipate contemporary design thinking. For fifteen years, until its premature closure in 1968, this school will train an elite that will profoundly transform German and international design.

Unlike American Mid-Century Modern which celebrates sculptural expression or Italian Design which values emotion, Ulm develops a systematic and scientific approach. Otl Aicher, Tomás Maldonado, Hans Gugelot: these theorists and practitioners integrate cybernetics, semiotics, and sociology into the design process. Their influence on Dieter Rams at Braun, on Lufthansa’s visual identity, on the design of systems rather than isolated objects still structures contemporary design.

What is the Ulm School

The Ulm School (HfG, 1953-1968) constitutes the most ambitious attempt to refound design on scientific bases after World War II. Founded by Inge Aicher-Scholl, Otl Aicher and Max Bill with financial support from the Geschwister Scholl Foundation (in memory of resistance fighters Hans and Sophie Scholl), the school aims to train designers capable of democratically shaping post-war society.

This ambition radically distinguishes Ulm from other schools. Where Cranbrook cultivates creative intuition and craft excellence, Ulm favors rational analysis and scientific method. Where Good Design defines aesthetic criteria, Ulm develops systematic processes. This methodological approach inscribes itself in the great history of design as an attempt to transform design into a scientific discipline.

Ulm structures its teaching around four departments: Product Design, Visual Communication, Information (added in 1958) and Construction (architecture). But above all, the school imposes an unprecedented theoretical curriculum: mathematics, physics, chemistry, psychology, sociology, semiotics, ergonomics. Students spend as much time in theoretical courses as in practical workshops.

This scientific rigor aims to go beyond craft empiricism and subjective intuition. The designer must understand industrial processes, master analytical tools, integrate human sciences. This ambition makes Ulm the precursor of contemporary design thinking, UX design, of all approaches that consider design as a methodological process rather than artistic talent.

Historical & cultural context

Post-war Germany must confront its Nazi past while rebuilding its future. The founding of Ulm is part of this context of moral refoundation and material reconstruction. Inge Aicher-Scholl, sister of Hans and Sophie Scholl (resistance fighters executed by the Nazis), wants to create an institution embodying the democratic values for which her brother and sister died.

Initial funding comes from the American Marshall Plan and the regional government of Baden-Württemberg. This transatlantic origin influences the school: numerous visiting American professors (notably Charles Eames), Anglo-Saxon theoretical references, international openness. Ulm thus escapes the provincialism that threatens isolated post-war Germany.

The context of industrial reconstruction also favors the school. German industry, destroyed by the war, must modernize radically. Companies like Braun (household appliances), Lufthansa (refounded airline), Olivetti (office machines) seek designers capable of creating modern identity. Ulm provides these skills.

The school also fits into the intellectual context of the post-war period. Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics (1948), Claude Shannon’s information theory (1948), rediscovered Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotics: all these emerging scientific disciplines offer new theoretical frameworks. Ulm systematically integrates them into design.

The ideological debate of the Cold War also plays a role. Facing Soviet socialist realism and American consumerism, Ulm proposes a third way: rational, democratic design that genuinely improves life without falling into commercial superficiality. This position, difficult to maintain, will contribute to the school’s premature closure.

Founding figures and evolution

Max Bill (1908-1994)

Max Bill, architect, designer, painter, theorist, former Bauhaus student, becomes Ulm’s first rector (1953-1956). His vision: reconnect with the Bauhaus legacy while modernizing it. He designs the school buildings—rigorous functionalist architecture—and structures the initial curriculum.

But Bill still favors the aesthetic dimension of design, the artistic approach. For him, the designer remains an individual creator endowed with talent. This vision quickly conflicts with the more scientific orientation defended by Otl Aicher and Tomás Maldonado. Bill resigns in 1956, giving way to methodological radicalization.

Otl Aicher (1922-1991)

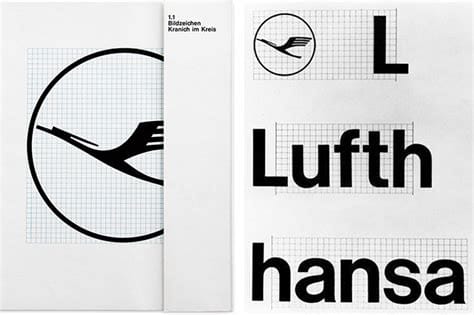

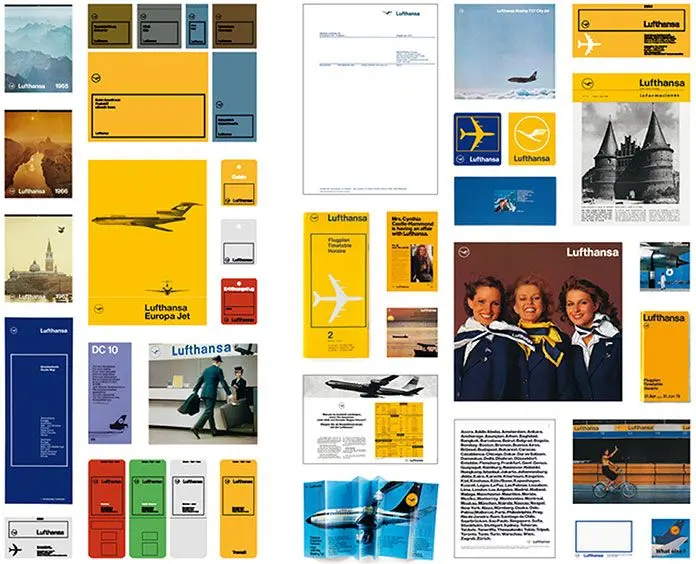

Otl Aicher, co-founder and central figure at Ulm until 1966, embodies the systematic approach. A graphic designer, he develops visual identity systems rather than isolated logos. His work for Lufthansa (1962) revolutionizes corporate design: strict modular grid, rational sans-serif typography (Univers), restricted color palette (blue/yellow).

His pictogram system for the 1972 Munich Olympics, developed after leaving Ulm, applies the same methodology: simple geometric forms, coherent system, maximum legibility. These pictograms, still used internationally, demonstrate the power of the systematic approach.

Aicher also theorizes extensively. His writings on visual semiotics, systems design, and the designer’s social responsibility structure Ulm’s thinking. His conviction: design is not art but a discipline serving clear communication and efficient use.

Tomás Maldonado (1922-2018)

Tomás Maldonado, Argentinian, joins Ulm in 1954 and becomes rector in 1964. He radicalizes the scientific approach, introduces cybernetics, information theory, and semiotics to the curriculum. For Maldonado, the designer must understand how technical and social systems work, not just create pleasing forms.

His approach, the most radical at Ulm, makes design an applied science. The design process must be rational, analyzable, reproducible. This extreme ambition pushes Bauhaus logic to its limits. It profoundly influences industrial design, particularly in technical fields (automotive, aeronautics, medical equipment).

Hans Gugelot (1920-1965)

Hans Gugelot, industrial designer, heads the Product Design department. Collaborating closely with Braun, he develops the minimalist aesthetic that will define the brand. His M125 shelving system (1956), modular and rational, illustrates the Ulm approach: not furniture but an adaptable system.

His collaboration with Dieter Rams at Braun structures post-war German design. Together, they create radio-phonographs, razors, calculators of radical formal purity. This aesthetic—flat surfaces, right angles, clearly expressed functions—becomes synonymous with German design.

Pedagogical and methodological principles

Scientific approach to design

Ulm imposes unprecedented scientific rigor. Students study mathematics (geometry, calculus), physics (materials, structures), chemistry (polymers, surface treatments), psychology (perception, ergonomics), sociology (uses, needs). This dense theoretical training aims to transform intuition into objective knowledge.

The design process itself becomes systematic: needs analysis, documentary research, ergonomic studies, tested prototypes, objective evaluation. No more spontaneous creation or artistic inspiration: design must result from rational analysis and justifiable decisions.

Semiotics and communication

The integration of semiotics (science of signs) revolutionizes graphic design. How do forms communicate meaning? How to optimize legibility? How to create coherent visual systems? These questions, treated scientifically via Peirce, Saussure, and Morris, structure visual communication teaching.

This approach generates systems design rather than isolated objects. A logo is not just a beautiful form but an element of a system including typography, colors, grid, applications. This systemic vision durably influences corporate identity, signage, and editorial design.

Cybernetics and systems

The introduction of cybernetics—the science of control and communication in systems—transforms product conception. A device is no longer an isolated object but a system interacting with the user. How to optimize these interactions? How to make interfaces intuitive? These questions anticipate contemporary UX design.

This systemic approach also applies to architecture and urbanism. Ulm develops rational planning methods, modular systems, and participatory approaches. These researches influence post-war German architecture.

Emblematic achievements

Lufthansa identity (Otl Aicher, 1962)

Lufthansa’s visual identity constitutes Ulm’s most influential achievement. Aicher doesn’t create a simple logo but a complete system: modular grid, Univers typography, blue/yellow colors, coherent application across all media (planes, uniforms, tickets, advertising).

This systematic approach revolutionizes corporate design. It demonstrates that corporate identity requires absolute coherence, that graphic design is not decoration but a communication system. All modern visual identities inherit this methodology.

Braun design (Hans Gugelot, Dieter Rams)

The Ulm-Braun collaboration produces iconic objects of German design. The SK4 radio-phonograph “Snow White’s Coffin” (1956), the hi-fi system (1960s), electric razors, calculators: all apply Ulm principles.

These products embody radical minimalist aesthetics: flat surfaces, right angles, neutral colors (white, black, gray), clearly expressed functions, no superfluous decoration. This approach, synthesized in Dieter Rams’ ten principles, massively influences contemporary design (notably Apple).

Modular systems

Ulm develops numerous modular systems: shelving, office furniture, exhibition systems. The approach: create combinable elements rather than fixed objects, allow adaptation to varied needs, facilitate evolution. This modularity anticipates contemporary concerns of flexibility and durability.

Pictograms and signage

Pictogram systems developed at Ulm (notably by Aicher for Munich 1972) establish international standards. Simple geometric forms, maximum legibility, systematic coherence: these principles still structure contemporary signage (airports, hospitals, public transport).

Closure and controversies

Ulm closes prematurely in 1968 after only fifteen years. Several factors converge. First, financial difficulties: the school, dependent on public subsidies, suffers budget cuts from the conservative Baden-Württemberg government which judges the institution too costly and politically suspect.

Second, ideological tensions. Ulm’s radical scientific approach displeases conservatives (too modernist) as well as the student left (too technocratic). The 1968 student movement, which contests technocracy and scientism, targets Ulm as a symbol of cold rationalism.

Finally, internal debates. The tension between aesthetic approach (Max Bill) and scientific approach (Maldonado) is never resolved. Some teachers and students contest hyper-rationalization, defend individual creativity. These conflicts weaken the institution.

The closure, traumatic, scatters teachers and students internationally. Paradoxically, this diaspora amplifies Ulm’s influence: alumni spread the methodology in schools and companies worldwide. The legacy endures well beyond the institution.

Influence and legacy

Contemporary design methodology

Ulm’s influence on design methodology is immense. The idea that design requires a systematic process—research, analysis, testing, evaluation—structures contemporary teaching and practice. Design thinking, popularized by IDEO and Stanford in the 2000s, directly inherits from the Ulm approach.

User research methods, ergonomic testing, objective evaluation: everything stems from Ulm’s conviction that design must be evidence-based, based on data and analysis rather than intuition.

Graphic design and visual identity

Modern graphic design—modular grids, rational typography, coherent identity systems—massively inherits from Ulm. The Swiss International Style, dominant in the 1960s-80s, directly extends Aicher’s approach. All contemporary corporate identities apply the systematic methodology developed at Ulm.

UX design and interface design

Ulm’s cybernetic and semiotic approach anticipates UX design (User Experience). How to optimize human-machine interaction? How to make interfaces intuitive? These questions, posed at Ulm in the 1960s for physical products, structure digital design today.

The principles of clarity, legibility, and systemic coherence developed at Ulm apply perfectly to digital interfaces. Ulm’s influence (via Dieter Rams) on Apple is explicit and recognized.

Criticism and limitations

The Ulm approach also faces legitimate criticisms. Hyper-rationalization can seem dehumanizing, excessive scientificity technocratic. The postmodern movement of the 1980s, particularly the Italian Memphis group, explicitly rejects Ulm’s cold rationalism, claiming emotion, decoration, and subjectivity.

The conviction that scientific approach can solve all design problems proves naive. Design also involves value judgments, cultural choices, and emotional dimensions irreducible to rational analysis. This limitation partially explains Ulm’s institutional failure.

Contemporary relevance

Despite criticisms, Ulm’s legacy remains extraordinarily relevant. Facing the growing complexity of systems (digital, urban, social), Ulm’s methodological, systemic, interdisciplinary approach offers valuable tools. Contemporary design, confronting ecological and social challenges, needs the analytical rigor that Ulm helped develop.

Designers among current great names like Dieter Rams (Ulm training), Richard Sapper, and Naoto Fukasawa extend the minimalist and systematic approach. Contemporary design schools—Stanford d.school, IDEO—directly inherit Ulm’s methodology.

Conclusion

The Ulm School (1953-1968) embodies the most radical attempt to transform design into a scientific discipline. By integrating cybernetics, semiotics, and sociology into the creative process, Ulm surpasses the Bauhaus legacy to develop a systematic methodology that still structures contemporary design.

This approach fundamentally distinguishes Ulm from contemporary movements. Where American Mid-Century Modern favors sculptural expression, Ulm imposes analytical rigor. Where Italian Design values emotion and poetry, Ulm defends rationality and clarity. Where Cranbrook cultivates creative intuition, Ulm develops objective methods.

The success of the Ulm approach—influence on Braun, Lufthansa, global graphic design, contemporary design methodology—proves its validity. Despite the institution’s premature closure, its legacy endures: every contemporary design school teaches methods inherited from Ulm, every professional designer applies systematic processes that Ulm codified.

Ulm’s legacy remains ambivalent. On one hand, the school demonstrated that design can be a rigorous discipline, that intuition can be complemented by rational analysis, that creativity benefits from methodology. On the other, hyper-rationalization can seem dehumanizing, excessive scientificity technocratic, systematic approach reductive.

Ulm’s contemporary relevance facing complexity challenges is striking. Designing digital systems, sustainable cities, efficient public services requires exactly the methodological rigor, interdisciplinary approach, and systemic thinking that Ulm developed. Design thinking, UX design, service design: all these disciplines directly inherit from the Ulm approach.

Creators like Dieter Rams, Richard Sapper, and Naoto Fukasawa extend Ulm’s requirement: radical simplicity, perfect functionality, methodological rigor. Their influence on contemporary design—particularly Apple—demonstrates the durability of Ulm principles. Jonathan Ive explicitly acknowledges his debt to Rams, thus indirectly to Ulm.

Half a century after its closure, the Ulm School fascinates through its intellectual ambition and methodological rigor. In a world saturated with superficial design and commercial styling, Ulm’s requirement—analyze rigorously, design systematically, evaluate objectively—offers a valuable antidote. Its message still resonates: design is neither just art nor just commerce, it’s a discipline that can and must rely on scientific knowledge and rational methods.

This conviction that design has intellectual responsibility—deeply understanding problems before proposing solutions, justifying choices through analysis rather than taste, evaluating results objectively—makes Ulm a perpetually current movement. Its legacy reminds us that creativity doesn’t exclude rigor, that innovation benefits from method, that intuition is enriched by knowledge. Even if Ulm’s pure rationalism showed its limits, the fundamental requirement—treating design as a serious discipline deserving the same rigor as sciences—remains an inspiration for all who refuse to reduce design to superficial styling or purely subjective expression.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.