Good Design Movement: The quest for democratic design

New York, 1950. The Museum of Modern Art inaugurates its first “Good Design” exhibition, organized by Edgar Kaufmann Jr. In the MoMA galleries, Scandinavian furniture, Japanese objects, and American ceramics coexist according to a single criterion: the intrinsic quality of design, regardless of price or prestige. While Mid-Century Modern celebrates American prosperity and Europe rebuilds, an international movement emerges around a fundamental question: what is “good design” and how can it be made accessible to all?

This quest, which would animate the 1950s-60s, transcends national borders. In New York, Edgar Kaufmann Jr. at MoMA defines the criteria for Good Design. In Germany, Dieter Rams at Braun translates these principles into iconic objects. In Italy, the Castiglioni brothers demonstrate that formal intelligence and economic accessibility are not mutually exclusive. Unlike the Bauhaus which imposes a method or Cranbrook which cultivates elitist excellence, the Good Design Movement proposes an ethic: creating simple, functional, durable, and accessible objects.

What is the Good Design Movement

The Good Design Movement designates less a unified style than a shared philosophy of design emerging in the 1950s-60s. Its ambition: to establish objective criteria for quality in design and make “good design” accessible to the greatest number. This prescriptive approach—defining what constitutes “good” design—distinguishes the movement from previous avant-gardes that favored formal innovation or artistic expression.

This movement builds on several convictions. First, design has a social responsibility: improving the daily life of all, not just an elite. Second, design quality is judged by objective criteria—functionality, simplicity, honesty, durability—not by fashion or prestige. Finally, “good design” must be economically accessible, democratic in its production and distribution.

This philosophy distinguishes itself from contemporary movements. Where Mid-Century Modern celebrates sculptural expression and prosperity, Good Design favors restraint and accessibility. Where Streamline stylizes to seduce, Good Design refuses superfluous ornamentation. Where Art Deco reserves luxury for the elite, Good Design aims for democratization.

The term “Good Design” itself, deliberately normative, reflects this prescriptive ambition. It aims to define and promote quality standards, educate the public, and guide producers. This pedagogical and militant dimension places the movement in the great history of design as an attempt to reconcile aesthetic excellence and social justice.

Historical & cultural context

The Good Design Movement emerges in the context of post-war reconstruction. Europe, devastated, must rebuild with limited resources. This economic constraint paradoxically favors innovation: how to create more with less, produce better with little? This question, both technical and ethical, structures design thinking in the 1950s.

In the United States, prosperity allows a different but complementary approach. MoMA, under the direction of Edgar Kaufmann Jr., launches the “Good Design” program (1950-1955): annual exhibitions presenting domestic objects selected according to strict criteria. These exhibitions, very popular, educate the American public in modern “good taste,” distinguishing real quality from superficial styling.

In Germany, the reconstruction context generates the Ulm school (Hochschule für Gestaltung, 1953-1968). Founded by Max Bill, a Bauhaus alumnus, this school reconnects with functionalist rigor while adapting it to post-war technologies. Ulm notably trains Dieter Rams, who will apply its principles at Braun.

In Italy, a distinct approach develops. Italian design of the 1950s-60s—Castiglioni, Magistretti, Zanuso—combines technical intelligence and formal elegance. The Milan Triennale becomes an international showcase for quality design. Companies like Olivetti, Artemide, and Kartell demonstrate that industrial production and aesthetic excellence can coexist.

Japan also contributes to the movement. The tradition of economy of means, the wabi-sabi aesthetic (beauty of simplicity and imperfection), and refined craft culture: all resonate with Good Design principles. Sori Yanagi, Isamu Noguchi: these creators embody a Japanese modernity that profoundly influences the movement.

The ideological context of the Cold War also plays a role. Good Design becomes a soft power weapon: demonstrating that democratic capitalism produces quality objects accessible to all, unlike standardized and mediocre Soviet production. International exhibitions, exchange programs, and publications spread this vision.

Aesthetic characteristics and principles

Good Design is defined less by specific forms than by guiding principles. These principles, formulated differently according to contexts but converging toward common convictions, structure the movement.

Dieter Rams’ ten principles

Dieter Rams (born 1932), design director at Braun from 1961 to 1995, formulates the most influential manifesto of Good Design: his ten principles. Developed in the 1970s but crystallizing the thought of the 1950s-60s, they define good design:

- Good design is innovative

- Good design makes a product useful

- Good design is aesthetic

- Good design makes a product understandable

- Good design is unobtrusive

- Good design is honest

- Good design is long-lasting

- Good design is thorough down to the last detail

- Good design is environmentally friendly

- Good design is as little design as possible (Weniger, aber besser)

These principles, particularly the last—”less but better“—become the mantra of minimalist design. They profoundly influence contemporary design, notably Apple, whose Jonathan Ive explicitly acknowledges his debt to Rams.

Simplicity and honesty

Simplicity structures Good Design aesthetics. No superfluous decoration, no deceptive styling, no gratuitous complexity. Forms derive from function, materials express themselves honestly, construction reveals itself clearly. This simplicity is not poverty but essence: achieving maximum effect with minimum means.

Material honesty also characterizes the movement. A plastic object doesn’t pretend to be metal, a plywood furniture piece doesn’t imitate solid wood. This authenticity responds to an ethical requirement: not to deceive the user, to respect the public’s intelligence.

Functionality and ergonomics

Function takes priority over formal expression. An object must first work perfectly, respond precisely to its use. This functional priority inherits from Bauhaus but is enriched by advances in ergonomics: understanding how humans actually use objects, adapting forms to human physiology and psychology.

Braun products illustrate this approach. Their radios, razors, calculators: all prioritize clarity of use, intuitiveness, efficiency. Controls are logical, indications readable, forms adapted to grip. This functionality doesn’t exclude elegance but subordinates it to use.

Durability and timelessness

Good Design aims for timelessness: creating objects that transcend fashions, remain relevant for decades. This ambition responds to economic requirements (durable objects) and ethical ones (rejection of planned obsolescence). Good Design creations—Superleggera chair, SK4 radio, Arco lamp—retain their relevance 60 years after their creation.

Constructive quality guarantees this durability. Robust materials, careful assemblies, impeccable finishes: everything aims for longevity. This quality requirement opposes the throwaway consumerism emerging in the 1960s.

Creators and emblematic achievements

Edgar Kaufmann Jr. and MoMA

Edgar Kaufmann Jr. (1910-1989), son of the patron of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, directs MoMA’s design department from 1946 to 1955. He launches the “Good Design” program that structures the movement. His selection criteria—simplicity, functionality, honesty, economic accessibility—define the standards.

The annual “Good Design” exhibitions at MoMA (1950-1955) present carefully selected domestic objects: furniture, lighting, tableware, textiles. This institutional validation legitimizes modern design, educates the American public, influences producers. Kaufmann proves that a major cultural institution can advocate for the democratization of design.

Dieter Rams and Braun

Dieter Rams embodies German Good Design. At Braun from 1955 to 1995, he creates more than 500 products that define the aesthetic of rational design. His SK4 radio-phonograph (1956), nicknamed “Snow White’s Coffin,” revolutionizes electronic design: white and metal casing, transparent cover, minimal controls. This formal purity shocks then seduces.

His later creations—hi-fi systems, electric razors, calculators—systematically apply the same principles. The 606 shelving system (1960), modular and timeless, still equips millions of homes today. Rams’ influence on contemporary design, particularly Apple, is immense and explicitly recognized.

The Castiglioni brothers in Italy

Achille (1918-2002) and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni (1913-1968) embody Italian Good Design, more playful and experimental than German rigor. Their approach: reuse existing industrial objects, repurpose materials, create with intelligence and humor.

Their Arco lamp (1962) becomes a modern design icon: stainless steel arc, Carrara marble base, aluminum shade. This floor lamp that illuminates like a pendant illustrates their formal intelligence. Their Mezzadro stool (1957)—tractor seat mounted on metal spring—exemplifies their playful approach to the ready-made.

Their creations—Taccia lamp, Toio lamp, Sirio telephone—combine perfect functionality and sculptural elegance. They prove that Good Design can be joyful without being frivolous, intelligent without being austere.

Scandinavian and Japanese design

Scandinavian design of the 1950s-60s—Hans Wegner, Arne Jacobsen, Verner Panton—naturally embodies Good Design principles. Simple forms, honest materials (light wood, leather, wool), impeccable functionality, relative accessibility: everything corresponds to the movement’s criteria.

Japanese design brings a complementary sensibility. Sori Yanagi (1915-2011), son of the mingei (folk craft) pioneer, creates objects of refined simplicity: his Butterfly Stool (1954) in molded plywood illustrates Japanese economy of means. This Eastern influence enriches Good Design with a contemplative and poetic dimension.

Olivetti and Italian corporate design

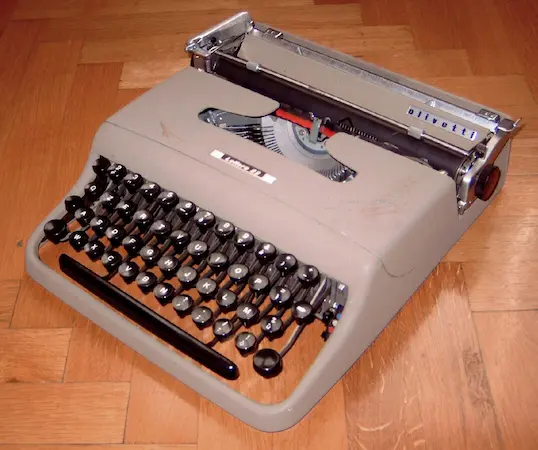

Olivetti, an Italian office machine company, becomes a model of Good Design applied on an industrial scale. Under the direction of Adriano Olivetti, a humanist visionary, the company employs the best designers: Ettore Sottsass, Mario Bellini, Marcello Nizzoli.

Their typewriters—Lettera 22 (1950), Valentine (1969)—combine technical excellence and formal elegance. Olivetti design demonstrates that complex industrial objects can be beautiful, that aesthetic quality improves the user experience, that companies have cultural responsibility.

Influence and legacy

Impact on contemporary design

The Good Design Movement profoundly influences design in the second half of the 20th century. The idea that design must meet objective criteria of quality, serve the common good, favor simplicity over ostentation: these convictions structure contemporary design.

The minimalist movement of the 1980s-90s directly inherits Good Design principles. “Less is more,” “form follows function”: these mantras, formulated earlier but popularized by Good Design, become dominant. Contemporary Scandinavian design, Japanese design, German design: all extend this tradition.

Apple and the renaissance of Good Design

Apple, particularly under the design direction of Jonathan Ive (1996-2019), explicitly reactivates the Good Design legacy. The iMac G3 (1998), iPod (2001), iPhone (2007): all apply Rams’ principles. Simplicity, functionality, honesty, attention to detail: everything evokes Braun of the 1960s.

This filiation, openly claimed by Ive, consecrates the enduring relevance of Good Design principles. It also demonstrates that “good design” is not obsolete in the digital age, that it can adapt to new technologies while retaining its fundamental values.

Criticism and limitations

The Good Design Movement also faces legitimate criticisms. Its prescriptive approach—defining what constitutes “good” design—can seem elitist and paternalistic. Who decides quality criteria? Can professional expertise judge popular taste?

The postmodern movement of the 1970s-80s explicitly rejects Good Design functionalism. Ettore Sottsass, Memphis Group: they assert that design can be playful, decorative, expressive, not just functional and sober. This salutary criticism enriches reflection on design.

The question of economic accessibility also poses problems. While Braun objects or Scandinavian furniture embody Good Design, their real price often reserves them for an educated middle class, not working classes. Democratic ambition meets economic constraints of quality.

Contemporary relevance

Good Design principles retain remarkable relevance facing contemporary challenges. Environmental sustainability requires robust, repairable, timeless objects—exactly what Good Design advocates. Digital minimalism reprises principles of simplicity and clarity. The circular economy values quality and longevity over planned obsolescence.

Contemporary creators among current great names like Jasper Morrison, Naoto Fukasawa, Konstantin Grcic, or Industrial Facility explicitly extend the Good Design legacy. Their approach—Super Normal, Thoughtless Design—updates 1950s principles for the 21st century.

Market and collections

Value of Good Design objects

The Good Design objects market has seen consistent appreciation since the 1990s. Dieter Rams’ Braun creations—SK4 radio, hi-fi system, calculators—reach several thousand euros for pieces in excellent condition. This appreciation reflects their recognition as modern design icons.

Good Design furniture—Scandinavian chairs, Italian lighting, shelving systems—also trades at high prices. An original Arco lamp by the Castiglionis approaches €3,000, a Butterfly Stool by Yanagi €800. These prices testify to the enduring recognition of their quality.

Reissues and continuous production

Unlike other movements, many Good Design objects remain in continuous production since their creation. Rams’ 606 system, Arco lamp, Scandinavian tableware: their timelessness allows uninterrupted commercialization for decades.

Official reissues by Vitsœ (for Rams), Flos (for Castiglioni), Vitra (for design classics) maintain excellent quality. These objects, accessible at current market prices, allow access to authentic designs, partially realizing the movement’s democratic ambition.

Institutional collections

MoMA in New York, the Vitra Design Museum in Germany, the Triennale Design Museum in Milan preserve the most important collections of Good Design objects. These institutions recognize the movement’s historical importance in the emergence of modern design.

Regular exhibitions reevaluate the Good Design legacy. “Less and More: The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams” (2009-2011), touring worldwide, consecrates the movement’s enduring influence. These events keep alive reflection on quality criteria in design.

Finally

The Good Design Movement embodies both an aesthetic and ethical ambition: defining and promoting quality standards in design, making “good design” accessible to all. This dual requirement—excellence and democratization—distinguishes the movement from elitist avant-gardes and mediocre commercial productions.

This approach radically distinguishes itself from previous movements. Where Bauhaus favors pedagogical method, Good Design proposes an ethic. Where Cranbrook cultivates craft excellence, Good Design aims for quality industrial production. Where Mid-Century Modern celebrates sculptural expression, Good Design advocates formal restraint.

The movement’s success—enduring influence on contemporary design, objects still produced 60 years after their creation, principles constantly reaffirmed—proves the validity of its approach. Dieter Rams, the Castiglionis, Scandinavian design: these creators demonstrate that simplicity, functionality, and elegance can coexist, that quality and accessibility are not necessarily opposed.

The Good Design legacy remains ambivalent. On one hand, the movement established quality standards, educated the public, positively influenced industrial production. On the other, its prescriptive approach can seem paternalistic, its economic accessibility remains limited, its formal sobriety can appear austere or elitist.

The contemporary relevance of Good Design principles facing ecological challenges is striking. Durability, quality, timelessness, rejection of planned obsolescence: everything resonates with current environmental imperatives. Good Design, conceived in the 1950s for economic and ethical reasons, proves prophetic facing the climate crisis.

Contemporary creators like Jasper Morrison, Naoto Fukasawa, Sam Hecht (Industrial Facility) explicitly extend the Good Design legacy by adapting it to 21st-century challenges. Their approach—which they call Super Normal or Thoughtless Design—updates principles of simplicity, honesty, and functionality for the digital and ecological era.

Half a century after its peak, the Good Design Movement fascinates through its moral requirement and enduring relevance. In a world saturated with mediocre objects, designed for rapid obsolescence, produced without ecological or social consideration, Good Design principles offer a valuable alternative. Its message still resonates: design has a responsibility—creating objects that genuinely improve life, that last, that respect users and environment.

This conviction that design must serve the common good, favor quality over quantity, aim for accessible excellence rather than elitist luxury or mass mediocrity, makes Good Design a perpetually current movement. Its legacy reminds us that aesthetics is never separated from ethics, that formal choices have social and environmental consequences, that “good design” is also a question of values. Even if the context has changed since the 1950s, the fundamental requirement of Good Design—creating beautiful, functional, durable, and honest objects—remains an inspiration for all who believe in the civilizing power of design.

Resources

Design Fundamentals

The Big Design History

From baroque salons to the radical lines of the 20th century, this timeline highlights the aesthetic revolutions that have shaped our everyday environment.

Read the page “The Big Design History”Hart Dictionary of Great Design Names

This dictionary lists the great names of design and decoration in alphabetical order. Discover the creators who have shaped contemporary art de vivre.

Read the page “Hart Dictionary of Great Design Names”History of Classic French & European Decorative Styles

Empire, Regency, Louis XV, Art Deco… This guide summarizes the decorative codes of each major European style.

Read the page “History of Classic French & European Decorative Styles”Hart Design Glossary A–Z

Sabre leg, patina, trimmings, caning… This glossary explains the technical and stylistic terms commonly used in the world of design and decoration.

Read the page “Hart Design Glossary A–Z”

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.