Understanding Louis XIII Style: The Dawn of French Grandeur (1610-1643)

The Louis XIII style is a French decorative, furniture, and architectural style developed between 1610 and 1643. It marks the transition from late Renaissance forms to a more architectural, rational, and structurally driven aesthetic, laying the foundations of French classical furniture.

The Louis XIII style refers to the furniture, interiors, and architectural language produced in France during the reign of Louis XIII and the regency of Marie de Medici. It is defined by geometric construction, clear volumes, and a strict hierarchy between structure and ornament. For the first time, French furniture asserts a coherent and autonomous identity.

Neither fully Renaissance nor yet Baroque, Louis XIII occupies a pivotal moment of balance. Decoration remains controlled, comfort improves, and furniture becomes more permanent, domestic, and rational. This period constitutes the intellectual and technical groundwork of the Grand Siècle.

Historical and Cultural Context

Louis XIII ascended the throne in 1610 at the age of nine. His reign was shaped first by the regency of Marie de Medici, then by the authority of Cardinal Richelieu, whose centralizing reforms transformed France into a structured modern state.

The nobility gradually abandoned fortified medieval castles in favor of urban hôtels particuliers and country residences designed for comfort and representation. Paris became a laboratory of modern urban planning, while craftsmanship organized itself through powerful guilds.

Italian influence slowly receded in favor of a French decorative language based on order, proportion, and construction. Furniture adapted to new domestic uses: private cabinets, specialized bedrooms, and salons dedicated to reception and conversation.

Architecture of the Louis XIII Period

Louis XIII architecture expresses the same principles found in furniture: clarity of structure, symmetry, and architectural restraint. Brick-and-stone façades, steep slate roofs, and disciplined proportions define the period.

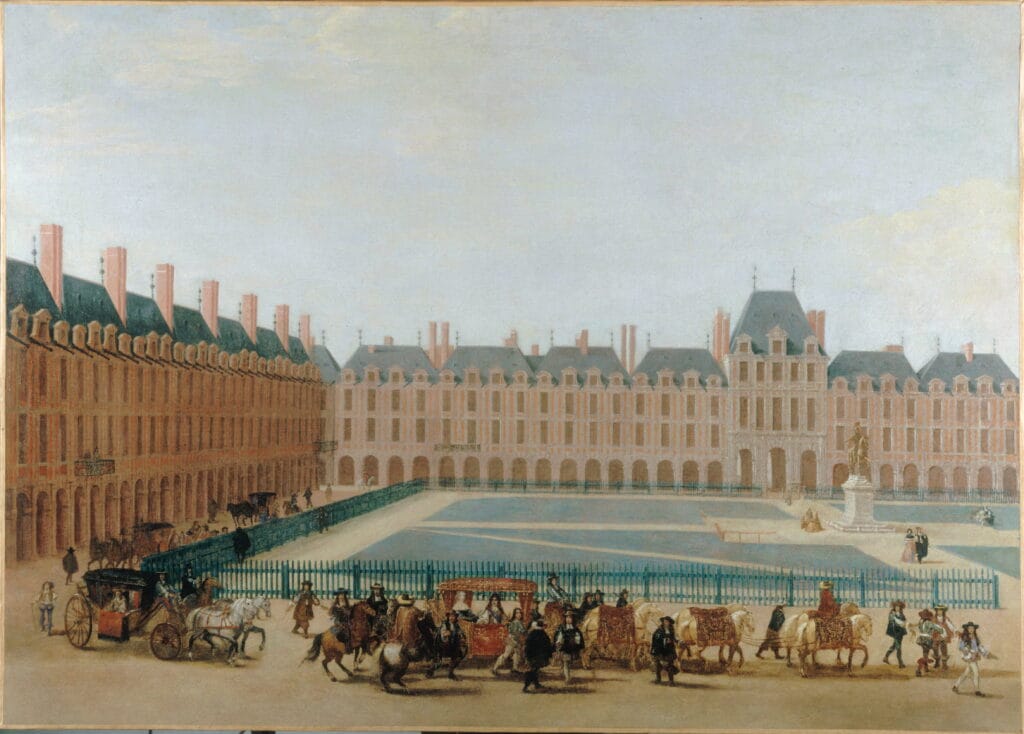

The Place Royale (now Place des Vosges) exemplifies this aesthetic: a unified urban composition based on rhythm, repetition, and architectural order. This model deeply influenced European urbanism.

Architects such as Salomon de Brosse (Luxembourg Palace) and François Mansart introduced monumentality without excess, favoring clarity, balance, and structural logic. Their work prefigures the rigorous classicism of Louis XIV.

Aesthetic and Technical Characteristics

Louis XIII furniture is conceived architecturally. Forms are rectilinear, volumes are heavy and grounded, and proportions are deliberately stable. Rectangles, cubes, vertical uprights, and framed panels dominate compositions.

Turned wood is central to the style. Legs and uprights frequently adopt chapelet turning, baluster forms, or spiral (Salomonic) columns. These elements are reinforced by a characteristic H-shaped stretcher, ensuring structural rigidity.

Walnut is the dominant wood, prized for its strength and warm tone. Oak remains common for internal structures. Indigenous woods are used for frames and seating, while exotic woods, primarily ebony, are reserved for decorative surfaces.

Diamond-point ornament (pointe de diamant) is carved in relief directly into solid wood panels. This is an architectural ornament inherited from the Renaissance, emphasizing volume and structure. It is not marquetry.

Marquetry, by contrast, develops as a planar decorative technique using veneers. It favors restrained geometric compositions (chevrons, lozenges, perspective cubes) applied flat to façades and tabletops. In the Louis XIII style, marquetry remains subordinate to construction.

Louis XIII Seating: Expert Typology

Seating furniture under Louis XIII undergoes a decisive transformation. While still formal and upright, it integrates comfort and upholstery more systematically than Renaissance seating.

Armchairs and Chairs with Arms

The armchair and chair with arms retain a low back inherited from the Renaissance: the back no longer rises above the sitter’s head. The uprights are slightly inclined, improving comfort while maintaining dignity.

Comfort increases through the introduction of rush (rottin) webbing and the emergence of horsehair pads (rarely exceeding 3 cm in thickness), covered with fabric, tapestry, or most often Cordovan leather. Decorative nails emphasize the geometry of the seat.

The base is generally in turned wood: chapelet, baluster, or spiral columns, reinforced by an H-shaped stretcher. The appearance of the console support and baluster enriches these bases. The so-called “os de mouton” leg refers to a specific articulated form carved in solid wood, characteristic of the style.

Chairs

Chairs follow the same structural logic as armchairs but without arms. Produced in sets, they reinforce symmetry and hierarchy in dining rooms and reception spaces.

Stools

Stools are essential auxiliary seating. Fully upholstered, square or rectangular, they rest on turned legs connected by stretchers. They function as occasional seating, footrests, or ceremonial supports.

Benches and Turned Benches

The bench remains a major piece of furniture, alongside stools and chests. It appears as a simple bench, turned bench (banc à tournis), arched bench, bench-chest, or chest-bench, often covered in black leather.

These forms reflect the persistence of medieval traditions while adapting to evolving domestic comfort.

Storage and New Furniture Types

The armoire emerges as a dominant storage form. Monumental and architectural, it features pronounced relief decoration, frequently with diamond-point panels.

The cabinet becomes a prestige object. Entire façades are composed of drawers, sometimes set on twisted column supports. The most precious examples are veneered in ebony and serve to store valuable objects and documents.

Writing tables and bureau tables develop, reflecting the rise of administration, correspondence, and intellectual life.

Materials, Techniques, and Craftsmanship

Structural frames rely on indigenous woods such as walnut and beech. Decorative surfaces employ exotic woods, primarily ebony.

The major technical innovation of the period is veneering (placage): the technique of covering non-precious structural wood with thick layers (10–12 mm) of exotic wood, allowing carved bas-reliefs. This marks the true emergence of cabinetmaking (ébénisterie) as a distinct discipline.

Guild organization, improved lathes, and refined tools allow unprecedented precision in turning, carving, and assembly, ensuring durability and structural intelligence.

Legacy and Influence

The Louis XIII style establishes the structural grammar of French furniture. Its discipline makes possible the decorative expansion of Louis XIV without sacrificing architectural coherence.

Revived in the 19th century through neo-Louis XIII and neo-Renaissance interpretations, it remains associated with solidity, authority, and permanence.

HART perspective: Louis XIII is not ornamental furniture. It is constructed furniture. Its relevance today lies in its intelligence, its respect for structure, and its refusal of superficial decoration.

Conclusion

The Louis XIII style represents a decisive turning point in European decorative history. It defines furniture as architecture, seating as structure, and ornament as discipline.

Four centuries later, its armchairs, benches, cabinets, and tables continue to speak a language of permanence. In a world of visual excess, Louis XIII reminds us that true elegance is built — not applied.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.