Less is a Bore”: How Postmodernism Set Design Free (1970–2000)

What is Postmodernism?

Postmodernism emerged as an intellectual and cultural movement during the 1960s and 1970s, positioning itself as a reaction against modernity and its certainties. Its influence spans philosophy, art, architecture, literature, and the social sciences.

Several defining features characterize postmodernism. First, a pronounced relativism: there isn’t one singular truth, but rather multiple truths shaped by cultural, social, and historical contexts. Second, systematic deconstruction of power structures and authority: who determines what’s true, beautiful, or legitimate? Finally, celebration of diversity, pluralism, and contradiction.

This movement also values hybridization—blending styles and references—alongside a certain irony or critical distance toward established conventions.

The Grand History of Postmodernism

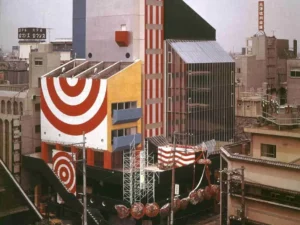

In 1972, American architect Robert Venturi, along with his wife Denise Scott Brown and collaborator Steven Izenour, published a book that would detonate like a bombshell in the insular world of design and architecture: Learning from Las Vegas. The book analyzed—seriously and without condescension—the casinos, motels, and commercial signage of the Las Vegas Strip, that empire of kitsch which the architectural establishment supremely despised. Even more provocatively, Venturi defended the notion that these “vulgar” architectures had something to teach us, that they communicated effectively with their audience, creating powerful emotional experiences. The scandal was absolute: how could a respected architect, Princeton-educated no less, betray modernist ideals so brazenly?

A few years earlier, in 1966, Venturi had already published Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, a foundational manifesto that dared to assert architecture could be “complex and contradictory” rather than “simple and pure,” that ornamentation wasn’t criminal, that history and cultural references had their place in contemporary creation. His pithy formula—“Less is a bore”—directly challenged Mies van der Rohe’s famous “Less is more,” central dogma of modernism. This dual theoretical and practical affront marks the beginning of a cultural revolution that would profoundly transform design, architecture, and visual arts for two decades: postmodernism.

Postmodernism: Key Dates

1950s-1960s: Early signs emerge in architecture and literature.

1970s-1980s: Significant development in philosophy (Lyotard publishes “The Postmodern Condition” in 1979) and the arts.

1980s-1990s: Movement reaches its apex in culture and intellectual debates.

Genesis of a Rupture: From Modernism to Postmodernism

The Crisis of Modernism: Disillusionment and Critique

Understanding postmodernism’s emergence requires first grasping the crisis of modernism that swept through the 1960s and 1970s. The modern movement, born in the early 20th century with the Bauhaus, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius, had carried a powerful utopia: creating a better world through design and architecture, rationalizing living spaces, industrially producing “good design” accessible to everyone. The precepts were clear: form follows function, ornament is crime, truth in materials, universalism, standardization. As demonstrated by the Good Design Movement, this project aimed at democratizing quality design.

Yet by the 1960s, this utopia revealed its limitations and perverse effects. Modernist housing projects, meant to solve the housing crisis, became dehumanized ghettos. Glass and steel towers in city centers, identical from Tokyo to São Paulo, created cold, interchangeable urban environments. The aesthetic uniformity imposed by the international style worldwide erased local specificities, building traditions, and cultural identities. Mass-produced modernist furniture seemed to ignore the diversity of bodies, uses, and social contexts.

Critical voices emerged, questioning modernism’s ideological foundations. British architect and theorist Reyner Banham questioned functionalism’s relevance in the consumer society era. American sociologist Jane Jacobs, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), dismantled modernist urban theories and defended the organic complexity of traditional neighborhoods. Historians like Vincent Scully rehabilitated vernacular and historical architectures that modernism had rejected as “retrograde.” This multifaceted questioning created the intellectual soil where postmodernism would germinate.

Theoretical Roots: From Venturi to Jencks

While Venturi laid postmodernism’s theoretical foundations in 1966, it was historian and critic Charles Jencks who baptized and systematized the movement. In The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (1977), Jencks identified a new architectural trend that rehabilitated ornament, color, historical reference, and symbolic communication. He theorized postmodern “double coding”: buildings could simultaneously address knowledgeable professionals (through sophisticated architectural references) and the general public (through familiar and accessible forms).

Jencks symbolically dated the “death of modern architecture” to July 15, 1972 at 3:32 PM, the time of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex’s demolition in St. Louis, archetype of modernist urbanism turned uninhabitable. This spectacular dating—probably apocryphal but symbolically powerful—marks a narrative rupture: modernism is officially over, make way for postmodernism. This simplistic periodization would be contested, but it provided a mobilizing narrative for architects and designers seeking to legitimize their anti-modernist explorations.

In France, philosopher Jean-François Lyotard theorized in The Postmodern Condition (1979) the end of modernity’s unifying “grand narratives”—progress, reason, universal emancipation. Philosophical postmodernism defended pluralism, fragmentation, cultural relativism against modernity’s universalist pretensions. These analyses, though initially focused on epistemology and political philosophy, also irrigated design and architecture debates: if unifying grand narratives are obsolete, why should design obey a single universal style?

The Cultural Context of the 1980s: Consumerism and Mediatization

Postmodernism in design emerged within a specific socio-economic context: the 1980s, marked by triumphant neoliberalism (Reagan, Thatcher), the explosion of consumer society, economic financialization, and above all an unprecedented mediatization of visual culture. MTV (founded in 1981) revolutionized visual codes with its saturated, fragmented, ironic clips. Advertising became increasingly sophisticated, self-referential, playing with cultural codes.

This culture of image and spectacle—what philosopher Guy Debord had anticipated in The Society of the Spectacle (1967)—created favorable terrain for postmodernism. Postmodern architects and designers didn’t reject this mediatization but embraced it: their creations were designed to be photographable, media-friendly, spectacular. Buildings became images before inhabited spaces, objects became signs before tools. This primacy of visual and symbolic over functional constituted a radical break with modernist ethos.

Postmodernism also coincided with the rise of cultural globalization and, paradoxically, with new awareness of local and minority identities. Postcolonial, feminist, LGBTQ+ movements questioned Western modernity’s universalist pretensions, revealing their ethnocentric and patriarchal blind spots. Postmodernism, with its proclaimed pluralism and celebration of difference, resonated with these identity claims, though relations between postmodernism and identity politics remain complex and sometimes contradictory.

Postmodern Architecture: Built Manifestos

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown: Architecture as Communication

The Venturi-Scott Brown duo embodied postmodernism’s intellectual and theoretical approach. Their practice didn’t seek formal exuberance for its own sake but developed scholarly architecture that integrated the vernacular, sophistication that didn’t exclude the ordinary. The Vanna Venturi House (1964), a residence Robert Venturi designed for his mother, became a built manifesto: façade with a “broken” pediment, references to traditional American domestic architecture reinterpreted with subtle irony, interior spatial complexity contradicting the apparent exterior simplicity.

Their National Gallery extension in London (Sainsbury Wing, 1991) demonstrated how postmodernism could dialogue respectfully with history without falling into servile pastiche. The façade adopted the materials and proportions of the adjacent neoclassical building but interpreted them with contemporary freedom. Interior spaces, far from mimicking historical galleries, created fluid pathways adapted to modern museography. This ability to synthesize tradition and modernity without denying either perhaps constitutes Venturi-Scott Brown’s most enduring contribution.

Their influence extends far beyond their built works. As educators (both taught at Yale, Penn, Harvard), they trained an entire generation of architects in critical perspective on modernism and openness to popular culture. Their methodology—analyzing vernacular and commercial architecture without prejudice, identifying what actually works in communicating with users—profoundly influenced contemporary architectural practice, well beyond stylistic postmodernism alone.

Michael Graves: Polychrome Postmodernism

If Venturi-Scott Brown represented intellectual and measured postmodernism, Michael Graves (1934-2015) embodied its exuberant and colorful version. Architect of the Portland Building (1982), one of the first openly postmodern public buildings in the United States, Graves transformed a banal municipal office building into a polychrome manifesto: façades decorated with stylized columns, pastel palette (salmon, cream, blue), pediments and arcades evoking classical architecture but treated deliberately “flat” and graphic rather than sculptural.

The Portland Building immediately sparked controversy: modernists saw kitsch regression, postmodernists joyful liberation. Graves defended his approach by invoking the need to create buildings “legible” and “welcoming” for the general public, unlike interchangeable and impersonal modernist glass towers. This populist rhetoric—the architect presenting himself as defender of people against the modernist elite—would recur in postmodern discourses, not without ambiguities since postmodern buildings often remained designed for cultural and economic elites.

Graves extended his postmodern vocabulary to object design, notably his prolific collaboration with Alessi and Target. His famous whistling kettle for Alessi (1985), with its red bird-shaped spout, became a postmodern design icon: functional object transformed into playful sculpture, organic and figurative references, vivid color, narrative dimension (the bird “sings” when water boils). This relative democratization of postmodern design through mass-market products (Target) contrasted with the Memphis Group’s elitism, though both movements shared similar aesthetics.

Philip Johnson and the AT&T Building: Corporate Postmodernism

Philip Johnson (1906-2005), former apostle of the international style and curator of MoMA’s foundational 1932 exhibition, executed a spectacular conversion to postmodernism in the 1970s. This apparent betrayal—one of modernism’s popes abandoning doctrine—shocked but also conferred institutional legitimacy on the nascent movement. The AT&T Building (now Sony Tower) in New York (1984), co-designed with John Burgee, became the emblem of corporate postmodernism: a 197-meter skyscraper crowned with a giant Chippendale pediment, ironic reference to 18th-century furniture at monumental scale.

This building crystallized postmodernism’s ambiguities: is it ironic critique of corporate pretension to appropriate history, or complicit celebration of economic power adorned with cultural references? Johnson himself cultivated this ambiguity, declaring sometimes that architecture should entertain, sometimes that it should serve power. This political ambivalence—does postmodernism serve critique or celebration of late capitalism?—runs through the entire movement and fuels passionate theoretical debates.

The AT&T Building nonetheless durably influenced corporate architecture: it legitimized the idea that company headquarters could be iconic and identity-defining rather than uniformly modernist. This lesson would be retained well beyond postmodernism stricto sensu: contemporary corporate architectures—think Norman Foster’s Apple Stores or BIG’s Google headquarters—all cultivate a distinctive visual identity, indirect legacy of postmodernism.

Postmodern Object Design: From Irony to Poetry

Philippe Starck: Designer Stardom

Frenchman Philippe Starck (born 1949) perhaps best embodies the postmodern designer as media star. Trained at École Camondo, Starck exploded onto the international scene in the 1980s with creations mixing diverted historical references, humor, theatrical flair, and technical sophistication. His design of François Mitterrand’s private apartments at the Élysée (1983-1984) propelled him to the forefront: ironic neo-baroque furniture, blend of contemporary objects and classical references, theatrical sense of staging.

Starck developed a recognizable formal vocabulary: tapered furniture legs in metal tubes evoking insect limbs, stylized organic forms, unexpected materials (transparent plastic, brushed aluminum, horn), references to Louis XV or Art Deco furniture reinterpreted in contemporary key. His “Costes” armchair (1984), created for Café Costes in Paris, with its three back legs and dark tensioned leather back, became emblematic of Parisian “trendy” style in the 1980s. His “Juicy Salif” citrus squeezer for Alessi (1990), arachnoid sculpture in cast aluminum whose functionality is questionable at best, incarnates postmodern design as conversational sculpture-object rather than optimal tool.

Starck mastered the art of communication and personal branding: provocative interviews, bold declarations (“Design is dead,” “Objects must have a soul”), collaborations with mass-market brands (Target, Décathlon) he claimed to “democratize” while maintaining luxurious creations for elites. This dual strategy—elitist AND popular design, ironic AND sincere, consumerism critique AND prolific producer—characterizes embodied postmodern ambiguity. Starck extends his work to today, evolving toward ecological discourse and more streamlined forms that dialogue with contemporary concerns, demonstrating postmodernism’s capacity to adapt to changing contexts.

Alessi and the “Dream Factory”

Italian company Alessi, under Alberto Alessi’s direction from the 1970s onward, became the quintessential laboratory of postmodern object design. Traditional metal housewares manufacturer since 1921, Alessi transformed into a “dream factory” collaborating with the greatest international designers and architects to create domestic objects transcending mere functionality. The strategy was explicit: transform banal utensils into objects of desire, inhabitable sculptures, narrative supports.

Alessi’s 1980s-1990s collections constitute a postmodernism anthology: the “Tea & Coffee Piazza” series (1983) invited eleven prestigious architects (Graves, Venturi, Rossi, Meier, Hollein) to reinterpret the tea service, producing sculptural pieces where each teapot, coffee maker, sugar bowl became mini-architecture. The “100% Make Up” series (1992) explored design as play and formal experimentation. Collaborations with Alessandro Mendini, Ettore Sottsass, designers from Italian Radical Design and the Memphis Group created a catalog where domestic ordinary became extraordinary.

This strategy raised essential questions about object status: are Alessi creations design or art? Tools or sculptures? Intended for daily use or contemplation? Alessi embraced this undecidability: objects could be simultaneously functional and sculptural, utilitarian and precious, industrial and artisanal. This dissolution of boundaries between traditional categories—art/design, luxury/everyday, serious/playful—characterizes postmodern approach and durably influences contemporary design, paving the way for objects deliberately positioned at the intersection of multiple worlds.

Postmodern Furniture: Between Citation and Innovation

Postmodern furniture is characterized by complex interplay of historical citations and contemporary reinterpretations. Designers like Paolo Portoghesi, Charles Jencks himself (who designed furniture besides theorizing), Robert A.M. Stern created pieces dialoguing with furniture history—neoclassical, baroque, Art Deco—but translated them into modern materials (laminate, tubular steel, plexiglass) and vivid colors signaling their contemporary and ironic nature.

Robert Venturi’s “Queen Anne” chair for Knoll (1984) exemplified this approach: it adopted an 18th-century Queen Anne chair’s silhouette but flattened it, simplified it, treated it as a plywood cutout decorated with patterns. The result was simultaneously familiar and strange, comfortable and ironic. This strategy of “deformed citation” allowed creating objects that were both new (no one had done exactly this) and old (everyone recognized the reference), rich in historical meaning but freed from submission to the past.

Other postmodern designers explored more experimental and sculptural paths. Gaetano Pesce, though having emerged from 1960s Radical Design, pursued in the 1980s-1990s postmodern work through his rejection of fixed typologies, use of unexpected materials (colored resins, industrial felt), irregular organic forms. His “Up” armchairs or translucent colored resin tables created objects seemingly still transforming, refusing perfect modernist finish in favor of an aesthetic of process and controlled accident.

Visual Codes and Postmodern Formal Vocabulary

Rehabilitation of Ornament and Color

One of postmodernism’s most radical gestures consisted of rehabilitating ornament, banned by modernism since Adolf Loos and his essay Ornament and Crime (1908). Postmodern architects and designers asserted that ornament wasn’t superfluous but meaning-bearer, communication vector, source of aesthetic pleasure. Façades adorned themselves again with columns, pediments, moldings, rosettes—stylized, flattened, sometimes ironic, but nonetheless present.

This rehabilitation accompanied a chromatic explosion. Where modernism privileged white, black, gray with occasionally a touch of pure primary color, postmodernism deployed complex palettes: pinks, salmons, turquoises, lavenders, yellows, often in combinations defying traditional good taste. These colors weren’t randomly applied but codified architectural elements (as with Michael Graves) or created visual hierarchies. Color became a full-fledged compositional tool again, as it had been in classical and baroque architecture.

Patterns and textures also returned: stripes, checks, marbles (real or imitated), terrazzo, mosaics. This sensory richness contrasted frontally with modernist asceticism. Postmodern architects defended this approach by invoking the richness of pre-modern architectural traditions and the necessity of creating stimulating and differentiated environments rather than uniform and neutral ones.

Double Coding and Stratification of References

Charles Jencks theorized “double coding” as postmodernism’s central characteristic: works functioned simultaneously at multiple reading levels. They could be appreciated naively by the general public (pretty colors, familiar forms) and learnedly by initiates who decoded cultural references, ironic citations, intertextual games. This stratification theoretically allowed reconciling high and low culture, expertise and accessibility.

In practice, this double coding created works of great referential complexity. A postmodern building could simultaneously cite the Roman Pantheon, a 1950s motel, Art Deco advertising, a comic strip, creating vertiginous cultural collages. This density of references could enrich aesthetic experience but also risked producing cacophony where everything equals everything, where sign accumulation replaces meaning construction. Postmodernism critics often denounced this sophisticated superficiality: many references, little depth.

Postmodernism also developed a collage and montage aesthetic: juxtaposition of heterogeneous elements, assumed stylistic ruptures, refusal of organic unity. A building could combine a neoclassical façade, exposed high-tech structure, and vernacular elements, without seeking to meld these elements into homogeneous whole. This approach, inspired by modernist collage (Picasso, Schwitters) but pushed further, celebrated fragmentation and heterogeneity as contemporary conditions rather than problems to solve.

Irony, Pastiche, and Claimed Kitsch

Irony perhaps constitutes postmodernism’s most characteristic attitude. Postmodern creators no longer naively believed in the possibility of pure creation, original, freed from history’s weight. They assumed everything had already been done, that we always create from preexisting forms, that absolute originality is a modernist illusion. Hence an ironic, distanced attitude that cites without fully adhering, that reuses historical forms while signaling their citation status.

This irony theoretically distinguished postmodern pastiche from simple historicist imitation. Postmodern pastiche was self-aware, it played with codes without claiming to authentically restore them. A giant Chippendale pediment atop a New York skyscraper (AT&T Building) didn’t pretend to be real Chippendale: it ironically cited this style to create meaning and recognition, while asserting its contemporary and artificial nature through absurd scale and incongruous context.

Kitsch, until then a pejorative term designating petty-bourgeois bad taste, found itself rehabilitated—at least partially. Theorists like Susan Sontag (in Notes on Camp, 1964) had prepared the ground by analyzing how certain forms of bad taste could be aesthetically appreciated. Postmodernism went further by actively celebrating certain kitsch forms: Las Vegas casinos, roadside motels, neon signs, theme park décors. This celebration nonetheless remained ambiguous: was it sincere affection or ironic condescension? Postmodern creators themselves often gave contradictory answers.

International Figures and National Variations

Frank Gehry: From Postmodernism to Deconstruction

American-Canadian Frank Gehry (born 1929) occupied a singular position: trained in modernist tradition, he evolved toward forms dialoguing with postmodernism while surpassing them toward what would be called architectural deconstruction. His own house in Santa Monica (1978), where he wrapped a banal suburban house in corrugated metal and wire mesh structure, manifested interest in raw industrial materials and destructured forms announcing his later works.

Gehry shared with postmodernism the rejection of modernist orthodoxy, interest in “impure” and “vulgar” materials (corrugated metal, raw plywood, mesh), valorization of visual complexity over reductive simplicity. But unlike classical postmodernists who cited architectural history, Gehry developed an original formal vocabulary: fractured volumes, undulating surfaces, apparently random assemblages that nonetheless created functional and poetic spaces.

His Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (1997), though built slightly after the classical postmodern period, prolonged certain postmodern intuitions: building as monumental sculpture, architecture as media spectacle, priority given to visual and emotional experience over functional rationality. Gehry demonstrated that modernism rejection could lead in multiple directions, not just toward historicist pastiche but also toward novel forms computer-generated. This diversity of post-modernist paths testifies to the initial rupture’s fecundity.

Bernard Tschumi and Rem Koolhaas: Critical Postmodernism

Franco-Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi (born 1944) and Dutchman Rem Koolhaas (born 1944) embodied an intellectual and critical version of postmodernism, influenced by Jacques Derrida’s deconstructivist philosophy and situationism. Their approach rejected both modernist orthodoxy AND superficial commercial postmodernism like Michael Graves’.

Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette in Paris (1982-1998) applied radical theoretical concepts: it refused the traditional park idea as organized nature and proposed a grid of “folies”—abstract red structures regularly dispersed—creating landmark and activity points without imposing a single pathway. This approach of indeterminate programming and spaces open to multiple uses profoundly influenced contemporary urbanism, anticipating current concepts of spatial flexibility and adaptability.

Rem Koolhaas and his firm OMA developed a practice coldly analyzing contemporary capitalism’s logics—consumption, mediatization, globalization—to extract architectural strategies. His book Delirious New York (1978) reinterpreted Manhattan’s history as retroactive manifesto of congestion and excess architecture, celebrating density and programmatic overload against modernist purity. This analytical and amoral posture—neither for nor against capitalism, but seeking to understand its mechanisms to better exploit them architecturally—characterized a certain postmodern avant-garde refusing both modernist utopianism and decorative cynicism.

Japanese Postmodernism: Arata Isozaki and Tadao Ando

Japan developed its own postmodernism interpretation, filtering Western concepts through local aesthetic traditions. Arata Isozaki (born 1931), trained under Kenzo Tange, figure of Japanese modernism, evolved toward sophisticated postmodernism mixing references to Western classical architecture (he participated in Memphis Group and designed for Alessi) and Japanese sensibility for ambiguous spatiality and impermanence.

His Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA, 1986) assembled primary geometric volumes (cylinders, pyramids, cubes) covered with red panels, creating a composition simultaneously evoking Buddhist temples, industrial warehouses, and Western formalist theories. This capacity to synthesize East and West without facile exoticism nor servile Westernization made Isozaki an essential cultural mediator, demonstrating postmodernism could be a tool for intercultural dialogue rather than mere exported Western fashion.

Tadao Ando (born 1941), self-taught turned international star, developed architecture of raw concrete and streamlined geometries seeming modernist at first glance. Yet his work dialogued profoundly with postmodernism through attention to space’s symbolic and spiritual dimension, sophisticated manipulation of natural light, references to Japanese traditions (Zen gardens, temples) reinterpreted in contemporary language. His Church of Light (1989) or Azuma House (1976) created intense spatial experiences transcending functionality to reach quasi-mystical dimension, demonstrating one could be postmodern without ornament or color, through sheer intensity of proposed spatial experience.

Postmodernism in Other Creative Disciplines

Graphic Design and Typography: Explosion of Codes

Postmodern graphic design broke spectacularly with Helvetica clarity and the rational grid of international style. Designers like April Greiman, David Carson, Neville Brody exploded established codes: superimposed illegible texts, broken grids, hybrid typographies mixing serif and sans-serif, chaotic digital collages. Ray Gun magazine, directed by Carson in the 1990s, pushed this approach to the extreme with layouts where conventional legibility was deliberately sacrificed for visual impact and formal experimentation.

This graphic revolution coincided with the personal computer’s arrival and first design software (PageMaker, QuarkXPress, then Adobe Suite). These tools democratized graphic production but also allowed unprecedented formal manipulations: distortions, superimpositions, effects impossible in traditional techniques. Graphic postmodernism fully exploited these possibilities, creating a digital-native aesthetic announcing 1990s-2000s web design.

Type foundries like Émigré, founded by Rudy VanderLans and Zuzana Licko, created postmodern typefaces rejecting modernist neutrality: crude bitmap fonts, strange hybrids, diverted historical references. These typographies became expressive tools rather than transparent information vehicles, rehabilitating the idea that text form fully participates in its meaning. This approach durably influenced contemporary design, up to digital interfaces multiplying expressive typographic choices.

Fashion and Textiles: From Vivienne Westwood to Moschino

Postmodern fashion in the 1980s-1990s shared with architecture and design a playful, citational, iconoclastic approach. Vivienne Westwood, already active in the 1970s punk scene, evolved toward sophisticated postmodernism mixing references to costume history (crinolines, corsets, 18th-century jabots), traditional Scottish tweed, and punk subversion. Her collections created temporal collages where Marie-Antoinette met contemporary urban rebellion, demonstrating clothing could be simultaneously historical and revolutionary.

Franco Moschino, with his eponymous brand, pushed postmodern irony to paroxysm: his creations parodied haute couture codes, integrated provocative slogans (“Stop the Fashion System!”, “Expensive Jacket”), diverted luxury brand logos. This internal critique of fashion system—made from within the luxury industry itself—perfectly incarnated postmodern ambiguity: subversion or complicity? Both simultaneously, in a posture fascinating and disturbing.

Jean-Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Gianni Versace developed maximalist aesthetics where baroque patterns, saturated colors, multiple references created sartorial spectacle aligned with MTV culture and 1980s hedonism. Their shows became theatrical performances rather than simple clothing presentations, transforming fashion into mass media and entertainment, strategy prefiguring spectacle and experience’s current importance in fashion industry.

Music and Pop Culture: From Sampling to Appropriation

Though postmodern music is a debated concept, certain 1980s-1990s musical practices manifested postmodern sensibility: sampling in hip-hop and electronic music created sound collages recycling and reinterpreting musical heritage, exactly as postmodern architects cited and diverted architectural history. Producers like DJ Shadow, The Avalanches or Fatboy Slim constructed entire tracks by assembling disparate fragments, creating new meaning through juxtaposition and montage.

The music video, dominant cultural form of the 1980s-1990s, massively adopted postmodern codes: cinematic citations, heterogeneous image collages, irony and second degree, narrative ruptures, contradictory aesthetics in a single piece. Directors like Jean-Baptiste Mondino, David Fincher (in his beginnings), Michel Gondry created visual universes dialoguing closely with postmodern design and architecture: same fragmentation, same irony, same refusal of organic coherence favoring heterogeneous montage.

Contemporary remix culture—mashups, internet memes, fanfiction—prolongs and democratizes these postmodern practices of appropriation and reinterpretation. Postmodernism, by legitimizing the idea one could create by recycling and reassembling rather than inventing ex nihilo, prepared the ground for these participatory cultural practices characterizing the digital era.

Critiques and Controversies: Postmodernism’s Blind Spots

Relativism and Loss of Criteria

The most fundamental critique addressed to postmodernism concerns its apparent relativism. If all styles are equal, if all references are legitimate, if irony justifies everything, how to establish quality criteria? How to distinguish good from bad design? Postmodernism, by rejecting modernist standards, risked sinking into “anything goes” preventing all critical judgment.

Critics like Kenneth Frampton denounced postmodern “populism” which, under democratization pretext, abandoned all civilizing ambition and merely reflected market tastes. Others, like Hal Foster, distinguished “postmodernism of resistance” (effectively critiquing modernism and capitalism) from “postmodernism of reaction” (merely decorating economic power complacently). In short, postmodernism wasn’t excluded from unresolved political and ethical tensions.

Philosopher Jürgen Habermas saw in postmodernism premature abandonment of modernity’s “unfinished project”—reason, emancipation, progress. For Habermas, yielding to postmodern irony meant renouncing critical tools necessary to effectively transform society. Interestingly, this “left” critique of postmodernism—as opposed to conservative critiques deploring bad taste—remained influential in contemporary debates on design and architecture’s social role.

Postmodernism and Neoliberalism: Complicity or Critique?

An influential Marxist critique, formulated notably by Fredric Jameson in Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), analyzed postmodernism as cultural logic of late capitalism. According to Jameson, postmodernism—with its fragmentation, eclecticism, superficiality, reduction of history to a repertoire of consumable styles—didn’t critique capitalism but constituted its perfect cultural expression.

The 1980s, quintessentially postmodern decade, were also those of neoliberal triumph (Reagan, Thatcher, financial deregulation, exacerbated consumerism). Architectural postmodernism primarily served corporations (spectacular headquarters), real estate developers (luxury condominiums), entertainment industry (theme parks, casinos, shopping centers). This social functionality of postmodernism—beautifying and culturally legitimizing triumphant capitalism—contradicted its subversive and democratic pretensions.

Postmodernism defenders retorted this critique confused postmodernism and postmodernity (contemporary socio-economic condition), that certain postmodernists (Tschumi, Koolhaas) effectively developed capitalism critiques, and that modernism also served the powerful (Mies built for corporations, Le Corbusier for dictators). Debate remains open, revealing movement’s constitutive political ambiguities, similar to those found in contemporary architecture having to negotiate between innovation and economic imperatives.

Environmental Questions and Sustainability

Postmodernism, by celebrating decorative excess, formal complexity, varied materials and multiple references, entered tension with emerging environmental concerns. A typical postmodern building—complex forms, multiple materials, abundant decorative details—consumed more resources in construction and presented more thermal bridges than a streamlined modernist cube. This energy inefficiency became problematic as ecological consciousness developed in the 1990s-2000s.

Moreover, postmodern irony and celebration of ephemeral (notably with Memphis) encouraged consumerist logic of rapid obsolescence: postmodern objects and buildings, deliberately “fashionable,” risked appearing dated quickly, favoring their replacement. This approach contrasted with modernist ambition to create timeless forms crossing decades. Paradoxically, certain 1920s-1930s modernist buildings remain current, while 1980s postmodern creations already seem aged.

Contemporary architects nonetheless seek to reconcile postmodern expressivity and sustainability, demonstrating one could create rich and varied forms while optimizing environmental performance. Biophilic architecture, for example, shared with postmodernism rejection of modernist austerity but oriented it toward nature reconnection rather than historical citation.

Legacy and Mutations: From Postmodernism to Contemporary

Postmodernism’s End: Return to Modernism or Transcendence?

Classical postmodernism ran out of steam in the 1990s. Several factors explained this decline: visual saturation (too many postmodern buildings created new uniformity), growing critical reaction, emergence of new concerns (environment, digital, globalization) demanding other responses. From the late 1990s onward, a partial return to modernism was observed, or rather to streamlined “neo-modernism”: simple forms, honest materials, dominant white, ornament rejection.

This neo-modernism—embodied by architects like John Pawson, Claudio Silvestrin, Alberto Campo Baeza—sometimes presented itself as reaction to postmodern chaos. But paradoxically, this return to simplicity was only possible because postmodernism had liberated possibilities: contemporary neo-modernism is a choice among others, not uncontested orthodoxy. One could today be modernist, postmodern, organic, high-tech, according to projects and contexts, without any style claiming universality. This assumed plurality perhaps constitutes postmodernism’s most enduring legacy.

Other paths emerged that were neither modernist nor postmodern in classical sense: Zaha Hadid’s parametric architecture, Patrik Schumacher, digitally generated organic forms, computational design. These approaches used digital tools to create novel forms, neither rational-modernist nor citational-postmodern, but issued from algorithms and generative processes. They nonetheless prolonged certain postmodern intuitions: complexity, visual richness, rejection of reductive simplicity, but in entirely new formal vocabulary.

Persistent Influence on Contemporary Visual Culture

Even if postmodernism as coherent movement belongs to the past, its influence profoundly irrigates contemporary visual culture. The 2010s-2020s aesthetic—particularly on social media, in young graphic design, “cool” brand identities—massively borrows from postmodern vocabulary: saturated colors, simplified geometries, heterogeneous collages, ironic references, style mixing. The 2010s “Memphis revival,” notably carried by Instagram, testified to this resurgence.

Contemporary interface design and UX design are also postmodernism heirs, particularly in their approach to storytelling and user experience. The idea that objects and spaces should “tell stories,” create emotional experiences, address different audiences simultaneously, comes straight from postmodern theories. Contemporary mobile applications, websites, digital services are often conceived as interactive narratives rather than simple functional tools.

Internet culture—memes, GIFs, remixes, fanart—functioned according to profoundly postmodern logics: appropriation, diversion, irony, citation, collage. Digital content creators never started from scratch but assembled, modified, commented on preexisting cultural materials. This creativity of reappropriation, which postmodernism had legitimized in “noble” arts, became mass cultural practice in the digital era. Postmodernism anticipated and theorized what became our dominant mode of cultural creation.

Lessons for Contemporary Design: Pluralism and Contextualism

Beyond specific forms that may seem dated, postmodernism bequeathed to contemporary design several enduring teachings. First, legitimacy of stylistic pluralism: there doesn’t exist one single universal “good design” but a multiplicity of valid approaches according to contexts, cultures, intentions. This lesson freed designers from anxiety of having to find THE perfect solution and allowed them to explore diverse paths adapted to specific situations.

Next, importance of context and meaning over form alone. Postmodernism recalled that objects and buildings aren’t merely assemblages of materials and functions but meaning-bearers, atmosphere-creators, communication vectors. This attention to design’s semiotic and experiential dimension profoundly influenced contemporary practices, from user-centered design thinking to brand experience strategies.

Finally, postmodernism demonstrated the possibility and value of creation dialoguing with history without servilely copying it. One could draw inspiration from the past, cite historical forms, while creating the new. This approach freed from modernist obsession with permanent “rupture” and “blank slate,” allowing cumulative creativity that enriched rather than erased. The best contemporary designs often know how to weave together tradition and innovation, local and global, familiar and surprising—synthesis that postmodernism, despite its excesses, helped make thinkable and desirable.

Conclusion: The Fertile Ambivalence of the Postmodern Project

Postmodernism remains, forty years after its apex, an object of fascination and controversy. Liberation movement or symptom of decadence? Design democratization or commercial cynicism disguised as subversion? Pluralist openness or paralyzing relativism? These questions continue dividing critics and practitioners, testifying to the irreducible complexity of the postmodern phenomenon.

What appears clearly with hindsight is that postmodernism definitively cracked modernist hegemony. After postmodernism, it’s no longer possible to naively believe in a single universal style, in a royal path of formal progress, in aesthetic choices’ ideological neutrality. This loss of innocence can be experienced as traumatic (how to create without certainties?) or liberating (finally free to experiment!). Contemporary designers navigate this ambivalence, oscillating between nostalgia for lost certainties and enjoyment of gained freedom.

Postmodern excesses—facile pastiche, gratuitous irony, superficial decoration—shouldn’t obscure its enduring contributions: ornament and color rehabilitation, stylistic diversity legitimization, attention to design’s symbolic and narrative dimensions, recognition that creation always happens in dialogue with history rather than ex nihilo. These achievements still nourish contemporary design’s most innovative practices, from smart homes orchestrating complex sensory experiences to digital interfaces telling stories by assembling cultural fragments.

Perhaps postmodernism was less a destination than a necessary transition: we needed to pass through this phase of irony, excess, unbridled experimentation to exit the modernist impasse and open new possibilities. Whether we build today in streamlined neo-modernist, organic biophilic, digital high-tech or eclectic hybrid style matters less than the fact we consciously choose among a plurality of legitimate options, rather than obeying a single dogma. This freedom of informed choice, this capacity to adapt our formal vocabulary to contexts and intentions, constitutes postmodern adventure’s most precious and least dated legacy.

In a contemporary world confronting immense challenges—climate crisis, growing inequalities, cultural fractures, digital transformation—design and architecture must find new paths. Neither austere modernist functionalism nor disengaged postmodern irony suffices. But the conceptual tools postmodernism forged—contextualism, pluralism, attention to meaning and experience, dialogue with history and diverse cultures—remain precious for inventing the forms and spaces we need. Postmodernism taught us we could be serious without being dogmatic, creative without rejecting history, contemporary without global uniformity. These lessons remain fertile for anyone seeking to design a world simultaneously beautiful, functional, diversified, and humane.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.