What Is the Chippendale Style? British Furniture and Elegance (1750–1780)

The Chippendale style emerged in England around 1750, at a time when the rococo refinement of French Louis XV still dominated Europe, while the Anglo-Saxon world was already beginning its transition toward neoclassicism.

Introduction

Chippendale style embodies the golden age of eighteenth-century English furniture. Between 1750 and 1780, Thomas Chippendale and his cabinetmaking workshop created a decorative vocabulary that synthesized diverse influences into a distinctly British aesthetic: french rococo, Chinese exoticism, neo-Gothic .

This style is distinguished by its refined eclecticism and technical virtuosity. Unlike more homogeneous continental styles, Chippendale embraces a multiplicity of sources: rococo curves, Chinese fretwork, and Gothic arches coexist harmoniously. This creative freedom, combined with excellence in execution, produces furniture that is both elegant and comfortable.

Why does this style matter today? Because it represents the first international style disseminated through printed catalogue. Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) became a reference manual, copied throughout Europe and America. This style also embodies the perfect balance between functionality and beauty and between tradition and innovation, qualities that make it still relevant today.

Historical & Cultural Context

Mid-eighteenth-century England experienced prosperity and expansion. The Industrial Revolution was beginning, international trade was intensifying, and the British Empire was extending its reach. An enriched middle class emerged, eager to furnish their homes with elegance.

The reigns of George II (1727-1760) and then George III (1760-1820) witnessed the flourishing of a refined society. Aristocratic country houses multiplied. London town houses competed in elegance. This demanding clientele required quality furniture that was both comfortable and aesthetically sophisticated.

Cultural exchanges intensified. The Grand Tour—an educational journey to Italy—exposed the British aristocracy to antiquities and the Italian Renaissance. Trade with China introduced porcelains, lacquers, and oriental textiles that fascinated. English gardens adopted Chinese elements: pagodas, bridges, and pavilions.

The neo-Gothic emerged in parallel. Romantic interest in the Middle Ages inspired architects and decorators. Horace Walpole transformed his villa at Strawberry Hill (from 1749) into a whimsical Gothic castle, launching an enduring fashion.

Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779), a cabinetmaker established in London, synthesized these influences. His workshop on St Martin’s Lane employed skilled craftsmen capable of executing complex designs. His publication of the Director in 1754 revolutionized the dissemination of furniture patterns, enabling provincial and colonial cabinetmakers to reproduce his creations.

Aesthetic Characteristics

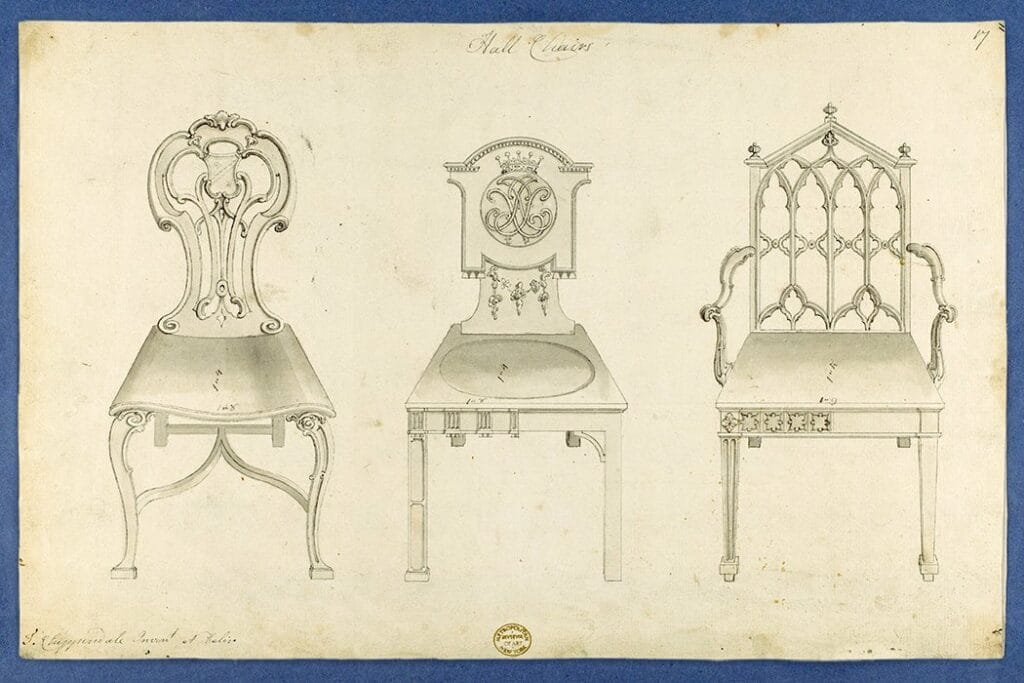

Chippendale style is recognizable by its mastered eclecticism. Three principal influences coexist: rococo (sinuous curves, controlled asymmetry), chinoiserie (oriental motifs, geometric fretwork), and Gothic (pointed arches, trefoils, arcading). This multiplicity, far from creating confusion, produces a unique decorative richness.

The proportions remain elegant without excessive lightness. Chippendale furniture possesses a reassuring solidity while avoiding heaviness. This elegant robustness responds to British sensibility that privileges durable functionality over fragile delicacy.

The dominant wood is mahogany, imported from the British West Indies. Its warm reddish-brown color, fine grain, and hardness make it an ideal material. Mahogany carves with precision, polishes beautifully, and resists wear. Its high cost signaled prestige. Walnut and rosewood occasionally appear in less prestigious pieces.

The carving achieves remarkable virtuosity. Chair backs are the most characteristic elements..It transform into wooden lace: volutes, scrolls, shells, and foliage interweave with millimetric precision. Furniture legs adopt varied forms: cabriole legs terminating in lion’s paw feet or ball feet, straight fluted legs for the later neoclassical style.

Chinese fretwork (geometric openwork cuttings) adorns table galleries, bed posts, and bookcases. These motifs, inspired by Chinese screens and lacquers, create sophisticated plays of light and shadow. Execution demands extreme skill: wood cut with fine saws, each element perfectly adjusted.

Openwork wood with geometric structure inspired by Chinese taste, characteristic of British fondness for exoticism in the mid-18th century.

Gothic motifs (ogival arches, trefoils, arcading) Gothic Style: The Art of Divine Light (1150-1500)appear especially in bookcases and cabinets. This Gothic vein, less frequent than rococo or chinoiserie, testifies to romantic interest in the Middle Ages. Proportions remain Georgian: Gothic becomes applied decoration rather than structure.

- Unabashed hybrid style: mixture of rococo, Gothic, Chinese, and sometimes classical influences.

- Still-curved structures: curved legs, supple lines, inherited from rococo taste.

- Frequent cabriole legs, often terminating in claws holding a ball (ball-and-claw).

- Pierced and carved backs: interlaced motifs, ribbons, hearts, refined intersections.

- Carved rather than veneered decoration: wood is worked in relief, with great virtuosity.

- Exotic motifs: Chinese lattice, pagodas, stylized bamboo, marked oriental inspiration.

- Visible Gothic influence: pointed arches, lancet motifs, decorative verticality.

- Dominant dark woods: primarily mahogany, sometimes walnut.

- Elegant but expressive furniture: decoration remains abundant, never strictly geometric.

- British spirit: formal freedom, eclecticism, fewer rules than in France.

Iconic Furniture

Chairs

Chippendale chairs represent the pinnacle of the style. The back—the true signature—appears in infinite variations. The ribbon back imitates bows and ribbons carved in solid wood with stunning virtuosity. The ladder back aligns carved horizontal splats. The splat back presents a central panel carved with volutes, shells, and foliage.

Cabriole legs, inherited from Queen Anne, terminate in ball and claw feet—an animal’s paw gripping a sphere. This form, derived from Chinese iconography (dragon holding a pearl), became emblematic of Georgian furniture.

The seat, often consisting of a drop-in frame (a type of removable upholstery), facilitates refurbishment. Upholstery—leather, velvet, damask, tapestry—harmonizes with the decoration (and with the seasons). Armrests, when present (armchairs), trace elegant curves terminating in volutes.

Tables

Dining tables adopt an ingenious extension system. Two round or oval half-tables separate, accommodating central rectangular sections. The mechanism allows adaptation to the number of guests. The legs—cabriole or fluted columns—solidly support the ensemble.

Tripod tables serve for tea or as side tables. Tilting tops allow storage against a wall. The carved central pedestal rests on three cabriole legs. The most refined present marquetry tops or are bordered with pie-crust edges (scalloped edges imitating pie crust).

Attributed to Thomas Chippendale.

Writing furniture combining architectural structure, restrained marquetry, and neoclassical elegance of late British taste.

Side tables (consoles) and card tables (gaming tables) combine elegance and functionality. Folding tops, secret compartments, felted surfaces for cards testify to British ingenuity.

Commodes & Chests

Chest of drawers (commodes) adopt solid rectangular forms. Facades in solid mahogany, handles in brass (often in the shape of drops or winged bats), feet in ogee or bracket give distinctive character. Serpentine fronts (undulating facades) add rococo sophistication.

Tallboys (high chests) superimpose two bodies of drawers. Crowning is often ornamented with a pediment—triangular, broken, or scrolled. These imposing pieces furnished aristocratic bedrooms.

18th-century British furniture blending rococo heritage, geometric marquetry, and emerging neoclassical rigor.

Bachelor’s chests—smaller, with a folding top surface forming a writing surface—respond to practical needs with compact elegance.

Bookcases

Chippendale bookcases achieve architectural monumentality. Structures with two or three sections, crowned with carved pediments. Glazed doors protect precious books while displaying them. The uprights adopt varied decoration: fluted columns, pilasters, Chinese fretwork, Gothic arcading.

Secretary bookcases combine an upper bookcase with a lower bureau. A fall-front conceals compartments, drawers, and secret spaces. These pieces, combining function and prestige, equipped libraries in country houses.

Beds

Four-poster beds dominated bedchambers. Four carved columns—often fluted, with capitals—support a canopy (tester). Curtains and hangings in precious textiles (damask, chintz, velvet) ensure privacy and thermal insulation.

Chinese beds adopt oriental decoration: pagodas crowning the columns, fretwork ornamenting the canopy, imitated or authentic lacquers. These exotic beds testify to triumphant chinoiserie.

Mirrors

Chippendale mirrors are distinguished by their elaborate frames. Carved and gilded mahogany, asymmetric rococo compositions, Chinese phoenixes and pagodas, neoclassical eagles and garlands ornament these frames. Girandoles (mirrors with candle branches) combine lighting function with sumptuous decoration.

Thomas Chippendale wasn’t merely a talented cabinetmaker: he was the first to understand that furniture could become a coherent stylistic language, reproducible and disseminable on a large scale.

His true stroke of genius rests on dual mastery: drawing and workshop organization. Chippendale conceived precise models, intended to be executed by a complete team of joiners, carvers, and specialized craftsmen.

With The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754), he transformed the profession: furniture became a design product, no longer solely an object resulting from isolated craftsmanship. His plates served simultaneously as catalogue, manual, and stylistic reference.

Chippendale didn’t create a single style, but a system: he synthesized Gothic, Chinese, and rococo influences into a clear grammar, adaptable to the tastes, budgets, and interiors of British high society.

The Director: Editorial Revolution

The publication of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director in 1754 revolutionized design dissemination. The first comprehensive catalogue of furniture patterns, it presented 160 engraved plates showing chairs, tables, beds, bookcases, and mirrors in varied styles.

The work addressed a dual audience: gentlemen wishing to furnish their homes tastefully, and cabinet-makers (cabinetmakers) seeking models to reproduce. The plates, accompanied by technical explanations, enabled fabrication by competent craftsmen even far from London.

Success was immediate. Second edition in 1755, expanded third edition in 1762. The Director was exported: American colonies and continental Europe adopted the models. Chippendale style thus became the first international style disseminated through printed book.

This dissemination explains regional variations. American Chippendale adapted models to local woods (cherry, maple), simplified carving, and developed distinctive characteristics. Irish Chippendale adopted slightly different proportions. These variations testify to the style’s creative vitality.

Interior Decoration

Georgian interiors furnished in Chippendale privileged restrained elegance. Walls were often paneled with painted panels (off-white, pearl gray, olive green) or hung with textiles (damask, chintz). Moldings—cornices, plinths, frames—remained relatively discreet compared to continental baroque.

Ceilings in stucco presented neoclassical decoration: garlands, rosettes, and medallions. Robert Adam and other architects created harmonious compositions where architecture, decoration, and furniture dialogued.

Marble fireplaces dominated rooms. Carved mantels, overmantels adorned with mirrors or paintings created focal points. Andirons and fire screens in brass or polished steel completed the ensemble.

Textiles played a crucial role. Curtains in damask or chintz framed windows. Carpets—Aubusson, Savonnerie, or increasingly British—warmed floors. Tapestries or Chinese wallpapers sometimes adorned entire rooms, creating exotic ambiance.

Lighting combined candles with maximized natural light. Crystal chandeliers, wall sconces, candelabra on tables multiplied light sources. Mirrors—above fireplaces, between windows—amplified available light.

Louis XV style (France, circa 1730–1760) embodies the apex of rococo: sensuality of lines, embraced asymmetry, free and flowing decoration.

Chippendale style (England, circa 1750–1780) developed at the same moment, but according to a radically different logic: eclectic, structured, and more architectural.

Same era, opposing intentions.

Structure

Louis XV: curved forms, undulating lines, silhouettes in movement.

Structure fades behind decorative élan.

Chippendale: legible and asserted structure, often straight or powerful legs, composition conceived as a framework.

Furniture is built before being decorated.

Symmetry

Louis XV: frequent rocaille asymmetry, free decoration, sometimes deliberately unbalanced.

Charm arises from irregularity.

Chippendale: compositions predominantly symmetrical, even when decoration is abundant.

British influence of classicism and rule.

Decoration

Louis XV: rocailles, shells, nervous foliage, arabesques.

Fluid decoration, almost pictorial.

Chippendale: eclectic vocabulary mixing Gothic, Chinese (chinoiseries), and classical references.

A synthesizing style, nourished by engravings and books.

Legs

Louis XV: cabriole legs, supple curve, continuous movement.

The leg participates in the furniture’s dance.

Chippendale: often straight legs, or ball-and-claw, sometimes carved, more massive and expressive.

Anglo-Saxon influence and taste for sculpture.

General Spirit Louis XV: French aristocratic art of living, sensuality, worldly refinement.

Chippendale: more intellectual and pragmatic aesthetic, conceived for the cultivated English bourgeoisie.

Less seduction, more construction.

Essential key to understanding: Louis XV privileges line and movement, Chippendale privileges structure and decorative vocabulary.

Two different responses to the same European era.

Heritage & Influence

Chippendale style durably influenced English-speaking furniture. In the United States, it became the dominant style in the colonies and then the young republic. Philadelphia, Newport, and Boston developed distinct regional schools. American Chippendale—often more restrained, adapted to local woods—furnished the homes of the Founding Fathers.

In the 19th century, the style experienced successive revivals. The Victorian era produced reproductions and adaptations. The Chippendale Revival of the 1870s-1900s equipped British and American bourgeois homes. These productions, often in quality solid mahogany, preserved the spirit if not the finesse of the originals.

The 20th century maintained the reference. Quality reproductions continued, destined for the high-end market. Contemporary designers revisited Chippendale motifs: stylized ribbon backs, modernized cabriole legs. The style proves its timelessness through this capacity to inspire successive generations.

In current interior design, Chippendale represents classic British elegance. Its furniture integrates harmoniously into traditional interiors or contrasts effectively with contemporary elements. This versatility explains the style’s enduring relevance.

Value & Current Market

Authentic Pieces

Period Chippendale furniture (1750-1780) reaches high prices. A pair of ribbon back chairs: £15,000 to £80,000 depending on carving quality and provenance. A set of eight chairs can exceed £200,000. Armchairs reach £8,000 to £40,000 per piece.

Tripod tables with carved tops: £5,000 to £30,000. Dining tables with extensions: £10,000 to £60,000. Monumental bookcases: £20,000 to £150,000 depending on dimensions and decoration.

Serpentine commodes: £8,000 to £50,000. Tallboys: £6,000 to £35,000. Mirrors with elaborate frames: £3,000 to £25,000.

Expertise is essential: distinguishing authentic Chippendale from Victorian productions requires meticulous examination. Specialized auction houses—Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonhams—organize regular sales. London antique dealers—Mallett, Apter-Fredericks—guarantee authenticity.

Reproductions & Revival

Victorian reproductions (1870-1900) offer acceptable quality: chairs: £800 to £3,000 per pair, tables: £1,500 to £8,000. Edwardian reproductions (1900-1920), often excellent, trade for £1,000 to £6,000 depending on pieces.

Quality contemporary reproductions by traditional cabinetmakers: chairs: £2,000 to £8,000 per pair, dining table: £6,000 to £25,000. These pieces, using solid mahogany and traditional techniques, offer durability and authenticity.

The market also offers affordable industrial reproductions: chairs: £300 to £1,200 per pair, tables: £800 to £3,500. Quality varies—examine construction (glued vs. pegged joints) and materials (solid mahogany vs. veneer on common wood).

Conclusion

Chippendale style represents the apex of Georgian furniture and one of the greatest achievements of British design. During three decades, Thomas Chippendale and his contemporaries created a decorative vocabulary that synthesized multiple influences into a coherent and distinctive aesthetic.

This synthesis produced furniture of exceptional quality. Superbly carved mahogany, elegant proportions, functional ingenuity, and mastered eclecticism make Chippendale a style that is both refined and practical, sumptuous and comfortable.

After Chippendale, the neoclassicism of Adam and Hepplewhite would introduce more streamlined lines. But Chippendale would remain the reference for classic British elegance. Its influence crossed the Atlantic, adapted to American colonial sensibilities, and inspired generations of cabinetmakers.

Because Chippendale style still speaks today. It reminds us that eclecticism can produce coherence when guided by sure taste. That functionality and beauty need not oppose each other. That tradition can welcome innovation without losing its soul. These pieces, after two and a half centuries, continue to furnish homes and institutions with distinction, testifying to that unique moment when British furniture reached unequaled perfection.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.