The Louis XIII style (1610-1643)

The Louis XIII style (1610–1643) marks a pivotal moment when France moves beyond the decorative legacy of the Renaissance to lay the foundations of 17th-century classicism. More structural than ornamental, it favors rigor, geometry, and interior architecture directly foreshadowing the Louis XIV style.

Do you know the Louis XIII style?

What is Louis XIII style? It is the French decorative and furniture language developed during the reign of Louis XIII, defined by visible construction, geometric framing, turned legs, and a strict hierarchy between structure and ornament. Think of it as architecture in miniature: heavy volumes, clear joints, disciplined decoration—built to last.

Louis XIII: The Birth of a French Art of Living (1610–1643)

The reign of Louis XIII marks a quiet revolution in French decorative arts. Under the influence of Richelieu and the court culture shaped by queens and salons, France develops an art of living that reconciles national tradition with major European influences.

This pivotal era was shaped by thirty-three years of political and cultural transformation and it culminates with the rise of Louis XIV, who would amplify and systematize his father’s aesthetic innovations into an absolute language of grandeur.

Foundational timeline:

• 1610–1643: Reign of Louis XIII (33 years)

• 1610–1660: Extended stylistic influence (roughly 50 years)

• European parallels: English Jacobean, early Italian Baroque

A society in transition

This period sees the emergence of a new French nobility emancipating itself from Italian models to shape a distinctly French taste. Court culture shifts: more interior life, more representation through domestic space, and a growing obsession with order, rank, and decorative coherence.

Anne of Austria, Marie de’ Medici, and Madame de Rambouillet embody this new French elegance. Prosperity supports the flourishing of French decorative arts and the rise of a national craftsmanship capable of rivaling Italian and Flemish productions.

The French craft revolution

The reign of Louis XIII witnesses the strengthening of guilds and trade corporations that structure and refine French production. Furniture becomes a field of expertise: joiners, turners, carvers, upholsterers, and metalworkers push technique forward and France starts building what will become its long-term supremacy in decorative arts.

- Clearly legible structure: visible joinery, assertive construction.

- Turned legs as a defining feature, often in “mutton bone” turning (os de mouton), baluster or bobbin forms.

- Visible stretchers (H- or X-shaped) connecting the legs and reinforcing stability.

- Heavy proportions: grounded furniture with no search for lightness.

- Chair backs mostly straight or only slightly reclined, narrow and vertical.

- Preference for local woods: walnut, oak, pearwood, beech.

- Sober, geometric mouldings, with strongly framed panels.

- Controlled carved decoration: stylised foliage, interlacing motifs, diamond-point panels.

- Late Renaissance and Flemish influences, preceding full French classicism.

- A transitional aesthetic between Renaissance heritage and the future Louis XIV style.

Louis XIII Architecture: Grandeur and Measure

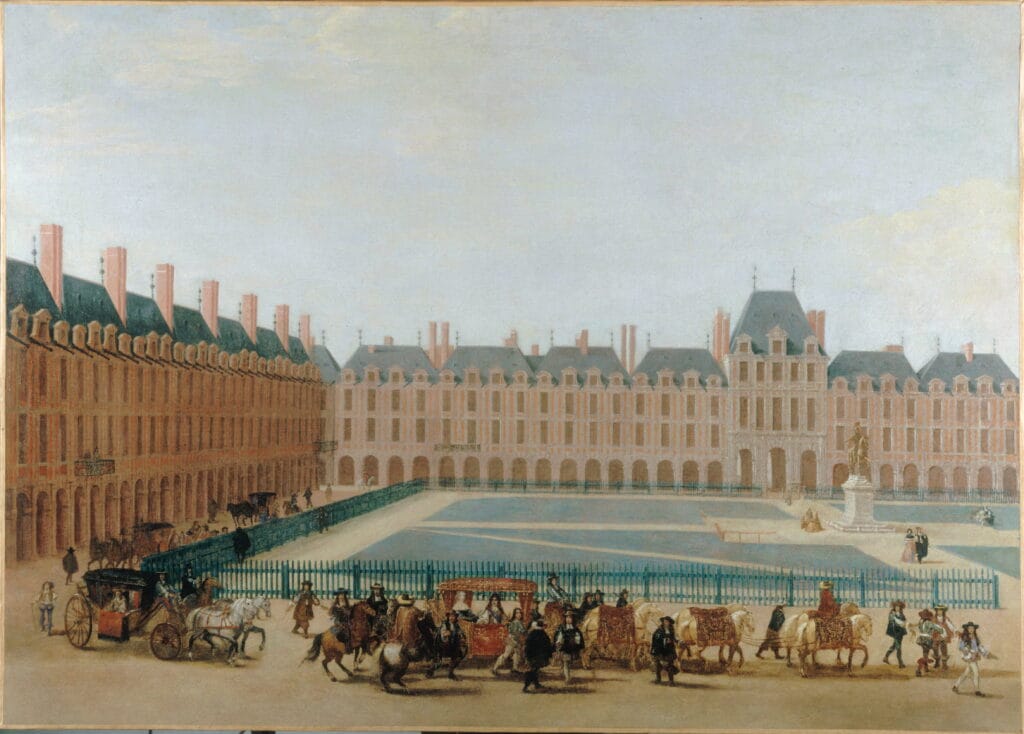

Louis XIII architecture expresses the same principles found in furniture: clarity of structure, symmetry, and restraint. Brick-and-stone façades, steep slate roofs, and disciplined proportions define the period and prepare the more absolute classicism of Louis XIV.

Key figures include Salomon de Brosse (Luxembourg Palace), Jacques Lemercier (architect for Richelieu), and François Mansart, whose rigorous compositions and structural intelligence deeply influenced French architectural culture.

Urban planning becomes a statement of power and order: the Place Royale model is one of the clearest visual signatures of the era, built on rhythm, repetition, and unity.

Aesthetic and technical codes

Louis XIII furniture is conceived as architecture in miniature: rectilinear frames, grounded volumes, strong rails, and a clear hierarchy between the structural carcass and decoration. It is built to be stable, readable, and permanent.

Turned wood becomes the most recognizable signature of the style. Legs and stretchers adopt rhythmic profiles: bobbin, baluster, string-of-beads (chapelet), and sometimes spiral turning. Most pieces are reinforced by a visible H-shaped stretcher, making the structure explicit and rigid.

Decoration remains disciplined. Diamond-point panels belong to a carved architectural tradition inherited from the Renaissance: they emphasize volume and framing rather than surface effect. (They are not marquetry.)

Marquetry, by contrast, develops as a planar veneer technique using restrained geometric compositions. In the Louis XIII spirit, it stays subordinate: the piece must read as constructed first, decorated second.

Materials: native woods – especially walnut and beech– dominate for frames and seating. Exotic woods, mainly ebony, appear in decorative elements and veneer work.

Technique spotlight: veneering (placage). Craftsmen begin covering a robust native-wood carcass with thicker precious-wood layers, allowing refined carving and bas-relief effects while preserving structural strength. This shift supports the emergence of cabinetmaking as a distinct discipline.

Louis XIII seating: expert typology

Seating furniture under Louis XIII undergoes a real transition. It remains upright and formal, but comfort begins to enter the equation through early upholstery solutions. Hierarchy is still strict: the seat is a social code as much as an object.

Armchairs and “chairs with arms” (chaises à bras)

Louis XIII armchairs and chaises à bras often keep a lower back inherited from the Renaissance: it no longer rises above the sitter’s head, and the uprights may be slightly inclined, an early move toward comfort without changing the formal posture.

Comfort improves through rush (jonc) stuffing and the emergence of early horsehair pads (often thin, around a few centimeters), covered in textile, tapestry, or frequently Cordovan leather. Upholstery remains restrained, but the shift is decisive.

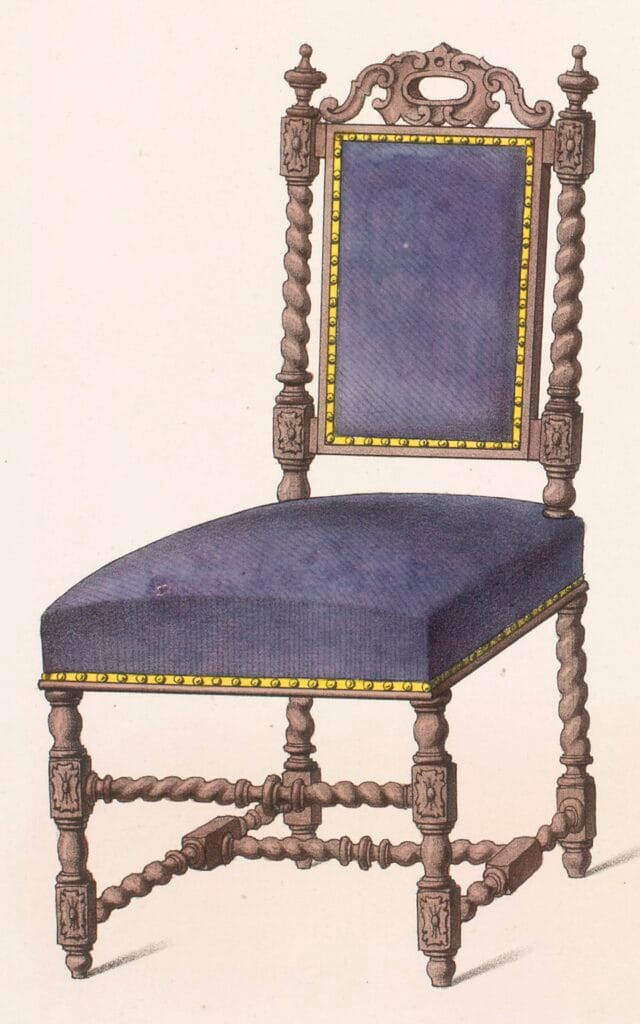

The chair (chaise)

The chair follows the same constructive logic as the armchair but without arms. It remains architectural, with turned legs and stretchers designed for rigidity and durability. Chairs are often made in sets to reinforce symmetry and order in reception rooms.

Some chairs stand on os de mouton (mutton-bone) legs: this is not a material, but a historical term for a specific articulated turned profile associated with early 17th-century French seating.

Stools (tabourets)

The stool remains essential: square or rectangular, built on turned legs with stretchers. It serves as auxiliary seating, footrest, or ceremonial support. In elite interiors, stools participate in a strict etiquette of rank and proximity.

Benches, chests, and the banc à tournis

Alongside stools, the bench and the chest remain major pieces in many households. They appear as simple benches, bench-chests, chest-bahuts, and archebenches—often covered in dark leather for everyday robustness.

The banc à tournis is a characteristic type: a long bench carried by turned legs (bobbin, baluster, string-of-beads, spiral profiles) linked by stretchers. It embodies a furniture culture still rooted in collective seating, before later centuries fully individualize the act of sitting.

Writing tables and early desks (tables-bureau)

Tables-bureau develop alongside administrative and intellectual practices. They typically adopt robust frames on turned legs with stretchers and may include drawers in the apron. Furniture becomes an instrument of work as much as a marker of status.

New furniture types and storage culture

Armoires gain importance as monumental storage furniture. Their façades often display deep relief and strong framing, frequently with carved diamond-point panels that reinforce the architectural reading of the piece.

The cabinet becomes the precious storage object of the era: its façade may multiply drawers, and the most refined examples are ebony-veneered. It is designed to protect valuables, documents, curiosities, and rare objects, an interior culture of privacy and ownership.

Legacy and influence

Louis XIII establishes the structural grammar of French furniture: visible joinery, rigorous framing, turned rhythms, and disciplined ornament. It makes the decorative expansion of Louis XIV technically possible—without losing the architectural logic that defines French classicism.

Revived in the 19th century through neo-Louis XIII and neo-Renaissance interpretations, the style remains associated with authority, durability, and honest construction.

HART perspective: Louis XIII is not decorative furniture. It is constructed furniture. Its relevance today lies in its intelligence, its respect for structure, and its refusal of superficial effects.

Conclusion

The Louis XIII style defines a decisive turning point in European decorative history. It frames furniture as architecture, seating as social code, and ornament as discipline.

Four centuries later, its chairs, tables, and cabinets still speak a language of permanence.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.