Gothic Style: The Art of Divine Light (1150-1500)

Introduction

Gothic style emerges in the mid twelfth century as an architectural and decorative revolution unlike anything Europe had seen before. Around 1140, Abbot Suger rebuilds the choir of the Basilica of Saint Denis near Paris. For the first time, stone seems to defy gravity. Walls grow thinner, vaults rise higher, and light floods the sacred space.

When stone learns to let light pass through, architecture becomes a spiritual experience.

Between 1150 and 1500, Gothic transforms European art and building culture. From France, the birthplace of the style, it spreads to England, Germany, Spain, and Italy. Each region adapts and reinvents it, creating striking variations around two obsessions: verticality and divine light.

Why does it still matter today? Because it embodies one of humanity’s greatest artistic adventures. Gothic cathedrals remain among the most audacious achievements ever conceived. Their technical sophistication, symbolic power, and timeless beauty still fascinate architects, historians, and travelers worldwide.

Historical and cultural context

The twelfth century marks a turning point in European history. After the most unstable centuries of invasions and fragmentation, society stabilizes. Cities grow again, trade expands, and new prosperity allows bishops and kings to launch monumental building campaigns.

The Catholic Church dominates spiritual and intellectual life. Cathedrals become symbols of episcopal power and collective faith. Every important city wants its cathedral, higher and brighter than the rival one. This competition fuels technical and artistic innovation.

The Crusades, launched from 1095 onward, reshape cultural exchanges. Knights and pilgrims encounter the East, its construction techniques and ornamental traditions. Byzantine and Islamic influences enrich the decorative vocabulary, especially in glass, pattern, and sculptural detail.

At the same time, universities develop. Paris, Bologna, Oxford become major intellectual centers. Scholasticism, with Thomas Aquinas, seeks to reconcile reason and faith. That search for rigorous harmony echoes in Gothic architecture, where every element follows a structural logic while serving a spiritual vision.

Gothic is born from a society in transformation: urban, prosperous, intellectually alive, and deeply religious. It expresses the confidence of a civilization that believes it can touch the sky.

Aesthetic features

Gothic is instantly recognizable by its vertical thrust. Everything rises: clustered columns, pointed arches that amplify the upward pull, spires that pierce the sky. This verticality translates the soul’s aspiration toward God.

The key technical breakthrough is the pointed arch and the rib vault. These systems concentrate thrust onto precise points, freeing the walls. Flying buttresses outside act as stone braces, countering the vaults. This skeletal structure makes the impossible possible: walls that can become almost entirely glass.

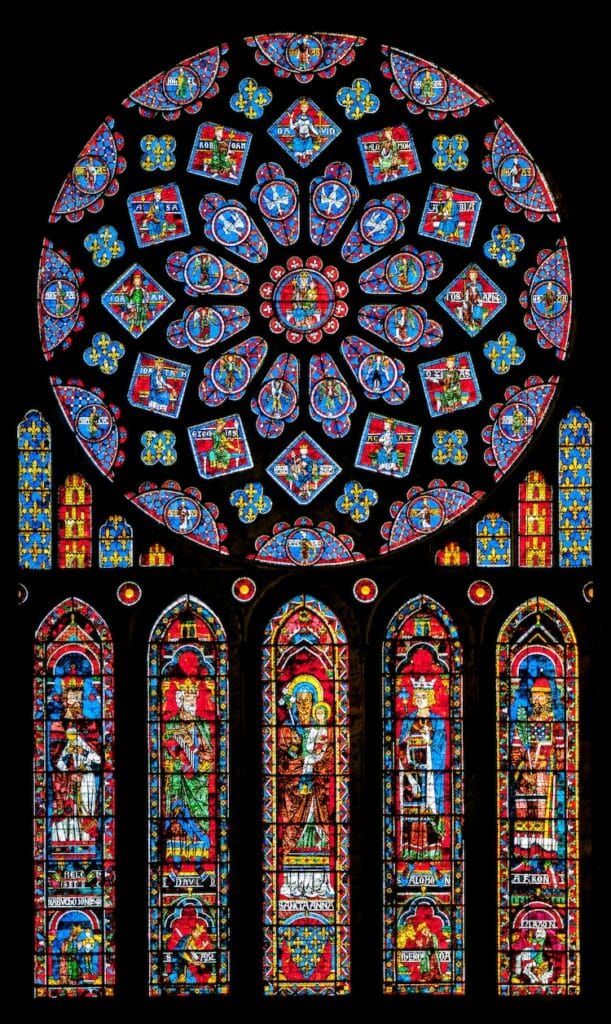

Light becomes the heart of Gothic aesthetics. Vast stained glass windows turn daylight into a colored symphony. Reds, blues, and golds filter through biblical scenes, creating a supernatural atmosphere. For medieval theologians, this colored light symbolizes divine presence.

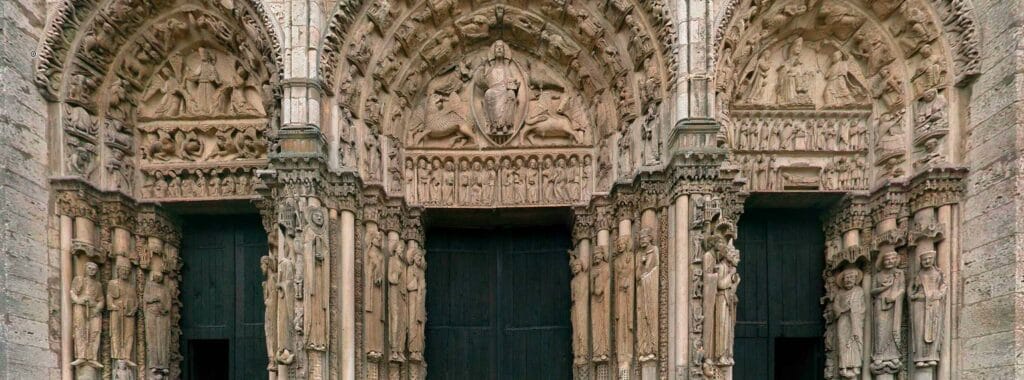

Ornament covers every surface. Sculpted capitals, fantastic gargoyles, narrative portals: stone becomes storytelling. Rose windows compete in geometric complexity. Each cathedral turns into a visual encyclopedia of Christian faith.

Vegetal decoration gradually becomes more stylized. Curled leaves, vines, thistles appear on capitals. In Flamboyant Gothic (fifteenth century), forms become more intricate: flame like curves, proliferating rib networks, and fan vaults of astonishing virtuosity.

- Pointed arches (ogival arches) that pull the eye upward.

- Rib vaults that channel weight into precise points.

- Flying buttresses outside, like stone braces.

- Very tall proportions: everything aims for vertical lift.

- Huge stained glass: walls feel like light, not mass.

- Rose windows with complex geometric tracery.

- Sculpted portals packed with narrative figures.

- Gargoyles and fantastic creatures on exteriors.

- Stone lacework: thin piers, openwork screens, tracery.

- Late Gothic effects: flame like curves and ultra complex ribs.

The main phases of Gothic

Early Gothic (1140 to 1200)

The first Gothic cathedrals still retain Romanesque weight. Saint Denis, Sens, Noyon test new techniques. Vaults rise to around 20 to 24 meters. Windows are still relatively small. But the revolution has begun.

High Gothic (1200 to 1350)

The peak of the style. Chartres, Reims, Amiens, Notre Dame de Paris reach a near perfect balance. Vaults climb to 35 to 42 meters. Stained glass takes over the walls. Sculpture achieves striking naturalism.

Portal figures come alive, faces show individual emotion, and sacred stone becomes human.

Rayonnant Gothic (1240 to 1350)

The Sainte Chapelle in Paris (1248) embodies this phase. Walls almost disappear in favor of immense glazing. Rose windows multiply and grow ever more complex. Architecture becomes stone lace. Technical virtuosity matters more than mass.

Flamboyant Gothic (1350 to 1500)

Late Gothic multiplies decorative effects. Flame like curves give the style its name. Vaults become extremely complex: liernes, tiercerons, hanging bosses. Saint Maclou in Rouen, the Rouen Palais de Justice, and the choir of Beauvais illustrate this final exuberance.

Romanesque: thick walls, round arches, smaller openings, heavy volumes.

Keywords: mass, round arch, dim interiors.

Gothic: pointed arches, rib vaults, flying buttresses, stained glass, vertical lift.

Keywords: height, light, structure as skeleton.

Renaissance: classical orders, symmetry, proportion, a return to Antiquity.

Keywords: balance, classical vocabulary, measured harmony.

Iconic architecture

Notre Dame de Paris

Begun in 1163 and completed by the fourteenth century, Notre Dame represents French High Gothic. A harmonious west facade, two square towers, a west rose window about 9.6 meters wide, and famous flying buttresses: it set the reference. Despite the 2019 fire, it remains a universal Gothic symbol.

Chartres Cathedral

Rebuilt after 1194, Chartres preserves one of the world’s most extraordinary ensembles of thirteenth century stained glass. Its deep blues create a unique atmosphere inside the nave. The sculpted portals form a vast visual library of medieval sacred and civic imagination.

Reims Cathedral

Cathedral of the coronation of French kings, Reims (1211 to 1275) dazzles through its sculpture. The famous “Smiling Angel” became an icon of Gothic statuary. The west facade counts more than 2,000 figures.

Canterbury Cathedral

English Gothic develops its own signatures at Canterbury. The cloister fan vaults (late fifteenth century) reveal a structural virtuosity specific to England. Horizontal volumes contrast with French vertical emphasis.

Cologne Cathedral

Started in 1248 and completed only in the nineteenth century following medieval plans, Cologne embodies the scale of German Gothic ambition. Its 157 meter spires dominate the Rhine. The building condenses centuries of Gothic evolution into a single silhouette.

Cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula

Built between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula represents Brabantine Gothic, a regional variation developed in the Southern Low Countries. Its powerful twin tower facade favors architectural clarity over exuberant decoration. Less openwork than major French cathedrals, it asserts a controlled monumentality.

Inside, verticality remains measured, volumes are legible, and light is filtered with restraint. This architecture expresses an ideal of balance and stability, halfway between French spiritual lift and Northern European structural rigor.

Gothic furniture and objects

Gothic furniture is rare. Most medieval pieces vanished through use, repurposing, or destruction. What survives often comes from churches and treasuries.

Gothic seating

In the medieval Gothic period (twelfth to fifteenth centuries), seating remains scarce and symbolic, reserved mainly for ecclesiastical and aristocratic elites. Chairs are often massive and architectural, echoing cathedral motifs: pointed arches, tracery, pinnacles, and carved foliage appear on backs and arms. The chest bench, both storage and seat, reflects the era’s functional logic. High backed chairs signal authority, while stools and benches serve the household.

In the nineteenth century, Neo Gothic reinterprets medieval forms with a more decorative and comfortable approach. Under Louis Philippe (1830 to 1848), influenced by British taste and by Viollet le Duc’s theories, French cabinetmakers such as Jeanselme produce chairs and armchairs featuring pointed arches, trefoils, and rosettes, combined with modern upholstery and bourgeois comfort.

Chests and coffers

The chest dominates secular Gothic furniture. Built in solid oak with forged ironwork, it serves as storage, seating, sometimes even a bed base. The finest examples display carved fronts: parchment fold patterns, arcades, and window like tracery that imitates cathedral architecture.

Gothic beds

The medieval Gothic bed is among the most precious and imposing pieces in a home, a marker of wealth and status. It is not only for sleeping: it is a semi public space where one receives and asserts rank. Built in solid oak or walnut, it often takes an architectural form with four carved posts supporting a canopy and heavy curtains in rich textiles that provide privacy and warmth. Posts and headboards echo cathedral vocabulary: pointed arches, pinnacles, finials, foliage, and sometimes family heraldry. Fully curtained canopy beds create a room within the room.

In the nineteenth century, the Neo Gothic revival reimagines these beds with romantic nostalgia, blending medieval aesthetics with modern comfort to create statement pieces for historicist interiors.

Choir stalls

Choir stalls, carved wooden seating for canons, are masterpieces of Gothic woodworking. Installed in rows along the choir, each stall has a folding seat with a misericord, a small carved support beneath that allows discreet leaning during long services, plus carved arms and partitions. Canopies and backs often reproduce cathedral architecture: pointed arches, pinnacles, and gables.

Stalls reveal a fascinating double iconography. The visible parts remain solemn, but hidden misericords often display profane, satirical, even grotesque scenes: fantastic beasts, everyday life, moral fables, burlesque figures. This contrast gives Gothic carvers a rare space of freedom inside a sacred setting.

Misericords, small supports under folding seats, open a world of fantasy: bawdy scenes, creatures, social satire. The freedom is surprising, and very human.

Stained glass

Stained glass is one of Gothic’s major arts. Blown glass, grisaille, and silver stain techniques create luminous images of exceptional richness. Master glaziers guard their recipes closely. Certain hues, especially deep medieval blues, remain notoriously difficult to replicate today.

Religious goldsmithing

Gothic reliquaries, monstrances, and chalices rival each other in sophistication. Gold, silver, enamel, and gemstones build miniature architectures. The Shrine of Saint Ursula (Bruges, 1489) by Hans Memling captures this goldsmithing spirit translated into painting.

Tapestries

Tapestries warm the walls of castles and palaces. The Lady and the Unicorn (around 1500, Musee de Cluny) represents the pinnacle of this art: six allegorical panels, a millefleurs background, and a poetic mystery that still fascinates.

Legacy and reinterpretations

Gothic experiences a first eclipse during the Renaissance. Italian humanists, obsessed with Antiquity, dismiss it as “barbaric” art and associate it with the Goths. The word “Gothic” itself is born from that disdain.

The nineteenth century rediscovers and rehabilitates the Middle Ages. Romanticism falls in love with cathedrals. Victor Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris (1831) alerts the public to endangered heritage. Viollet le Duc restores, and sometimes reinvents, French Gothic monuments.

Neo Gothic triumphs in religious and civic architecture. In England, the Parliament of Westminster adopts the style. In France, Sainte Clotilde in Paris illustrates the revival. In the United States, entire universities are built in Neo Gothic: Yale, Princeton, Duke.

In the twentieth century, Gothic influence shifts. Art Nouveau borrows vegetal curves. German Expressionism admires dramatic verticality. Contemporary architecture still dialogues with Gothic through height and light, sometimes in modern cathedrals or bold sacred projects.

In popular culture, Gothic fuels the imagination: fantastic novels, horror cinema, and today’s “goth” aesthetics. That fascination proves the style’s enduring symbolic power.

Market and value today

Authenticity and rarity

Authentic Gothic furniture is extremely rare on the market. A fifteenth century Gothic chest in good condition can reach very high prices depending on carving quality and provenance. Copies and nineteenth century Neo Gothic pieces are common, so expert appraisal is essential.

Sculpture, virgins, saints, and architectural fragments can command serious sums. Museum quality thirteenth century stone statues in excellent condition are exceptional rarities. The market rigorously separates medieval works from Neo Gothic production.

Works of art

Medieval stained glass can reach very high prices when it appears at auction, and institutions often acquire these treasures quickly. Gothic goldsmithing is even rarer. Exceptional reliquaries can exceed major thresholds.

Neo Gothic

Nineteenth century Neo Gothic furniture is a more accessible entry point. “Cathedral chairs” and Gothic revival bookcases appear regularly on the market, with wide price ranges depending on quality, provenance, and maker.

Major auction houses and specialized dealers handle medieval and Neo Gothic material. For serious acquisitions, choose sellers who provide documentation and expert guarantees.

Conclusion

Gothic is one of the high points of Western artistic creation. For three and a half centuries, builders, sculptors, glaziers, and goldsmiths pursued one vision: to lift matter toward light, and to create on earth an image of Paradise.

This technical and spiritual ambition produced masterpieces that still feel impossible. Vaults that challenge gravity, stained glass that turns light into poetry, sculpture that captures human emotion: Gothic remains extraordinary.

After Gothic, the Renaissance will impose other values: Antiquity, humanism, geometric rationality. Yet Gothic never truly disappears. It returns in the nineteenth century, inspires Art Nouveau, and haunts the contemporary imagination.

Because Gothic still speaks to us. It reminds us that a civilization can choose apparently impossible challenges and achieve them. That beauty can be born from the tension between technical constraint and spiritual ambition. That art, when it aims for the absolute, can touch eternity.

The cathedrals are still here, after eight centuries, bearing witness to that faith in humanity and in God that animated their builders. That may be the true Gothic miracle: creating works that outlive time and continue to move, inspire, and question each new generation.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.