Consulate Style: The French Art of Refined Creation (1799–1804)

Between the Directoire and the Empire, the Consulate style (1799–1804) established a tempered neoclassical sobriety: forms became purer, lines straightened, but without yet tipping into imperial monumentality.

The furniture favored clarity of volumes, function, and discreet ornamentation inspired by antiquity (stylized palmettes, rosettes, fillets). Light woods and mahogany dominated, often enlivened by fine gilt bronzes. It’s a style of stabilization: a return to order that already announced the more assertive language of the Empire.

- Straight, clean, proportioned: upright lines, legible volumes, calm geometry.

- Restrained decoration: palmettes, rosettes, fillets, more stylized than theatrical.

- Mahogany + fine gilt bronzes: precise chasing, measured placement.

- Obvious in-between: denser than Directoire, less monumental than Empire.

Consulate Furniture: Perfection, Balance and Modernity

The Consulate period (1799–1804) represents the most “intelligent” phase of French neoclassicism: it refines without impoverishing. Decoration becomes rarer, but execution quality, precision of proportions, and mastery of materials become the true luxury. This pivotal period in Western design history marks a decisive transition between republican lightness and imperial grandeur.

- Clean lines and controlled geometry: nothing gratuitous, everything is proportion.

- Mahogany (solid or veneered) + fine gilt bronzes: restrained decoration, precise chasing.

- Sober motifs: palmettes, laurel, fillets, rosettes — more stylized than theatrical.

- Measured monumentality: more “present” than Directoire, less demonstrative than Empire.

Formal revolution: Consulate furniture perfected decorative refinement. Cabinetmakers favored purity of line and excellence of proportion over ornamental profusion. This modernity would durably influence Western furniture art and lay the foundations of modern rational design.

Among woods, cabinetmaking workshops readily worked mahogany for its depth and natural nobility, enhanced with gilt bronzes of geometric design: an elegant presence, never invasive.

Ornamentation became more learned and more discreet: ebony fillets, geometric marquetry, chased bronzes, sometimes a few contrasts (light woods/dark woods, bronze/lacquer) for a calm sophistication. This decorative vocabulary, codified in the decorator’s vocabulary, established a formal grammar that would remain influential.

Technical perfection: the Consulate aimed for perfect balance between aesthetics and use. It’s a style “of stability”: prestigious enough to represent emerging power, refined enough for daily life, translating Bonaparte’s desire to establish a new order without renouncing the gains of the Revolution.

This formal perfection already heralded the imperial excellence to come. The era drew from Greco-Roman antiquity with new erudition: architectural forms inspired by temples and basilicas, geometric motifs drawn from ancient friezes, mythological references borrowed from Roman heroes, but always restrained, never ostentatious.

One also sees a discreet Egyptomania (preparing for the Empire’s enthusiasm following the Egyptian campaign of 1798–1801): sphinxes, palmettes, pharaonic details slipped in like learned signatures, not as demonstrative spectacle.

The ingenuity of cabinetmakers refined a more functional typology, adapted to the new uses of a reorganizing society: bourgeois comfort, domestic intimacy, workspaces, measured representation. Consulate interiors distinguished themselves through their stripped-down nobility and refined functionality.

Consulate Furniture: Types and Innovations

Seating: Toward Formal Perfection

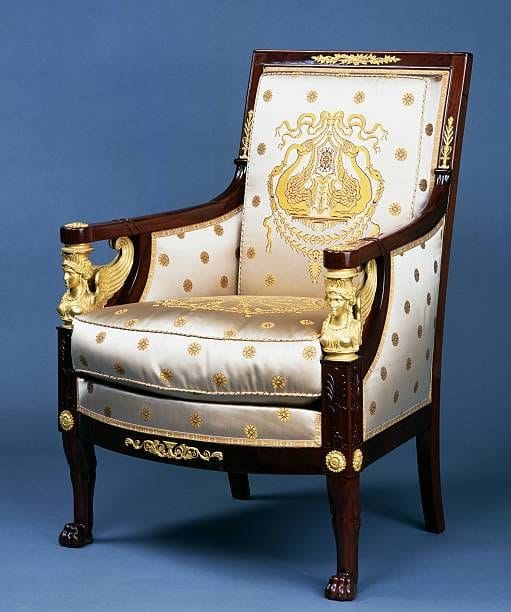

Consulate seating achieved a rare equilibrium: classical reference plus modern comfort. Forms became clearer, more architectural, with a rigor reminiscent of design before its time. Legs drew inspiration from Greek klismos chairs, backs adopted curves from Roman seats, but everything was recalibrated for contemporary use.

Ornamentation concentrated on essentials: gilt bronzes of great finesse (rosettes, palmettes, laurel friezes), precise caning that visually lightened the structure, mahogany wood whose natural depth sufficed to create nobility. Gondola chairs stabilized in a perfectly controlled curve; the straight-backed armchair became emblematic of this period of political consolidation; bergères retained their comfort but shed all superfluity; curule stools (inspired by Roman magistrates’ seats) gained sculptural clarity.

The Consulate paradox: while structures were perfected technically, seat upholstery paradoxically became more austere. Upholstery fabrics stiffened, padding thinned, angles became sharper, almost angular. This textile austerity reflected the martial spirit of the Consular regime: Bonaparte imposed a new discipline readable even in seat comfort. Upholstery techniques now favored tight stretches, regular stitching, strict geometry that sacrificed softness for bearing. As if the austerity of the new Consular monarchy and its martial ideal were directly reflected in the era’s comfort, imposing physical as well as moral rectitude.

Tables: Geometry and Nobility

Formal innovation: the Consulate table favored architectural forms and nobility of materials within sophisticated simplicity. Tops (often in solid mahogany, marble, or veneered precious woods) were enhanced by structured bases: fluted central column, tripods inspired by ancient altars, pyramidal geometric bases, chased bronzes positioned at points of visual tension.

Salon tables (pedestal tables, gaming tables) adopted circular or polygonal forms, with impeccable geometry testifying to cabinetmakers’ mathematical mastery. Work tables (flat desks, secretaries) developed a more modern ergonomics: well-conceived drawers with interior divisions, proportions adapted to prolonged sitting posture, daily use assumed without compromising elegance.

Commodes and Storage: Functional Purity

Consulate commodes and storage furniture aimed for useful purity: legible facades organized in symmetrical drawers, controlled volumes without unnecessary overhang or projection, bronzes more refined than spectacular (ring handles, discreet keyhole escutcheons, elegant sabots). These were pieces that “held” a room through their geometric structure and sober presence, not through ornament. Secretary desks enjoyed particular success, combining storage, work surface and privacy.

Beds: Simplicity and Controlled Comfort

The Consulate bed perfected the “boat” form inherited from the Directoire and gained visual stability: more architectural lines with equal-height headboards, deep mahogany whose horizontal grains emphasized the elongated form, measured gilt bronzes (palmettes at corners, sober friezes). It announced the grand parade beds of the Empire (crosswise beds, monumental canopies), but with more restraint. The bed remained a functional piece before becoming a political manifesto.

Objets d’Art: Technical Excellence

The Consulate pushed decorative objects to great heights: clocks (often with Egyptian or mythological themes), lighting fixtures (candelabra, torches, Carcel lamps), mantelpiece garnitures, small sculpted bronzes. This was the period when people understood that decorative objects could be miniature architecture: considered structure, balance of masses, details chased with the same attention as a monument.

The bronzes of Thomire (Pierre-Philippe Thomire, 1751–1843, chaser and bronze-worker to the powers that be) established an ornamental grammar that would dominate the entire 19th century: allegorical figures, caryatids, sphinxes, architectural bases. Consular silverwork (Biennais, Odiot) refined a more geometric and cleaner aesthetic, adapted to the new codes of bourgeois dining and official ceremonies.

Directoire (1795–1799): lighter, more “republican,” discreet decoration, slender furniture, tapered legs, still revolutionary spirit.

Consulate (1799–1804): more structured, denser, mahogany more prominent, bronzes more assertive but still measured, political stabilization visible in forms.

Conclusion: The Consulate, Laboratory of Empire

The Consulate style constitutes far more than a simple transition: it’s a formal laboratory where the innovations that would define Empire style crystallized. In just five years (1799–1804), French cabinetmakers, bronze-workers and decorators established a vocabulary of perfection that would serve as reference for all of Europe.

This period of political stabilization can be read in every piece of furniture: controlled geometry heralded imperial order, measured austerity of upholstery prefigured court protocol, increasingly assertive classical references prepared legitimization through history. When Bonaparte crowned himself emperor on December 2, 1804, the style was already ready: all that remained was to amplify it, monumentalize it, load it with imperial symbols (bees, eagles, crowned Ns).

The Empire (1804–1815) would take up all Consular codes while pushing them toward theatricality: bronzes multiplied, dimensions amplified, Egyptomania became spectacle, symmetry turned to obsession. But it was indeed the Consulate that laid the foundations of this grandeur, with a formal intelligence and restraint that, in retrospect, confer upon it a modernity perhaps superior to its sumptuous successor.

After Napoleon’s fall, the Restoration (1815–1830) retained part of this heritage while reintroducing rocaille elements, then Charles X style (1824–1830) lightened forms and brightened woods, preparing 19th-century eclecticism. But the Consulate would remain, in French furniture history, that rare moment of balanced perfection: neither too much nor too little, just what’s needed.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.