Transition Style: Early Neoclassicism (1750-1770)

The Transition style is neither an official “period style” nor a movement with a manifesto.

It belongs to no single reign. Instead, it names a moment in French taste, right at the hinge between the last rocaille inventions of Louis XV and the early neoclassical impulse that would define Louis XVI.

Introduction

In France, the Transition style rose from a quiet shift in sensibility. By the middle of the 18th century, Louis XV curves could feel almost too fluent, too decorative, too incessant. Rocaille asymmetry, shells, and rockwork motifs were still admired, but they started to call for something else: a return to order, without sacrificing the elegance already mastered.

Between 1750 and 1774, Parisian cabinetmakers, bronze workers, and designers found their answer. They kept the comfort and softness inherited from the previous reign, then slowly introduced symmetry, clearer geometry, and antique references. Not as a rupture, but as a recalibration. The result was a new kind of balance, and it would soon open the door to full neoclassicism.

This stylistic moment, now called the Transition style, feels like the French taste at its most controlled. It is not rocaille extended, and it is not neoclassicism fully declared. It is an equilibrium, where curves remain, but lines begin to lead. Where ornament still exists, yet structure starts to speak.

Born in Paris and quickly adopted across francophile Europe, the Transition style remains one of the most cherished by connoisseurs. Its brief lifespan, the technical excellence of its finest pieces, and the precision of its proportions make it a high point of 18th-century French cabinetmaking.

.

Historical & Cultural Context

The 1750s were a turning point in France. Louis XV still reigned, but the century was changing its mind. The Enlightenment had momentum, and Parisian salons became laboratories of ideas. In 1751, Diderot and d’Alembert launched the Encyclopédie. Reason, order, and measure rose to the top of the cultural hierarchy, carried by an elite newly fascinated by Antiquity.

Decorative arts followed the same current. The excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) revealed a new ideal of beauty: calmer, clearer, more structured. From 1752 onward, Count of Caylus published his Recueil d’antiquités. Egyptomania and a growing Greek taste began to shape the visual imagination of the period.

At the same time, a critical reaction formed against rococo excess. People began to challenge the systematic asymmetry, the ornamental overflow, the never-ending vocabulary of shells and rocailles. In 1754, Cochin the Younger, an engraver and theorist, famously attacked what he saw as frivolous decorative clutter.

Out of these two forces came the Transition style: fidelity to Louis XV craftsmanship, and a growing appetite for antique discipline. It is the perfect expression of an era that refused brutal change, yet quietly prepared the neoclassical future.

Aesthetic Characteristics

The Transition style is defined by a precise equilibrium. Straight lines begin to hold the architecture of the piece, but curves remain, softened and controlled. Legs become more rectilinear, often still gently shaped near the top, and already hint at the fluted vocabulary that will dominate under Louis XVI.

Ornament changes its language. Rocaille shells and agitated asymmetry fade. In their place come motifs that feel more measured: Greek keys, beading, ribbons tied into knots, symmetrical rosettes. Gilt bronzes grow more architectural too. They frame, underline, and articulate, rather than taking over the surface.

Materials remain noble: mahogany, rosewood, and palisander sit beside Oriental lacquers and richly veined marbles. Gilt bronzes keep their extraordinary quality. The difference is in the intent. Everything becomes more disciplined, more structural, and more legible.

Marquetry reaches a new level of sophistication. Perspective cubes become a signature motif, a geometric illusion that plays with depth and perception. Floral marquetry becomes more stylised and more symmetrical. Diamonds, checkerboards, and architectural compositions reveal a fresh appetite for order.

- A clear return to symmetry: more axial composition, mirror-like balance, less rocaille caprice.

- Curves still present, but controlled: tighter profiles, cleaner outlines, fewer free-flowing waves.

- Decoration becomes more classical: knots, ribbons, garlands, and beading gradually replace shells and rocailles.

- Early antique vocabulary: egg-and-dart, suggested fluting, ordered acanthus leaves.

- A cinched apron, but taut: still curved, yet without the signature Louis XV “dance.”

- Less pronounced cabriole legs: the silhouette moves toward straighter, more architectural supports.

- Underframes matter less: emphasis shifts to continuous lines and controlled profiles.

- Tops become calmer: tomb-shaped outlines may remain, but in a more restrained form.

- Mouldings are corrected: frames and panels become more regular, with fewer shaped contours.

- Overall feel: Louis XV calmed down, with Louis XVI already visible in the structure.

Key Makers & Figures

Jean-François Oeben

A German-born master cabinetmaker established in Paris, Jean-François Oeben (1721–1763) embodies the technical brilliance of the Transition style at its highest level. His furniture combines remarkable mechanical ingenuity with a refined sense of proportion, balancing the lingering curves of Louis XV with a newly disciplined geometry.

His most celebrated work, the Bureau du Roi commissioned for Louis XV in 1760, stands as one of the masterpieces of French decorative arts. Conceived as a cylinder desk of unprecedented complexity, it required years of development and an extraordinary command of marquetry, bronze work, and hidden mechanisms. Oeben did not live to see its completion, yet his vision shaped its entire structure.

In Oeben’s work, the Transition spirit is unmistakable. Comfort and elegance remain, but they are now governed by structure, symmetry, and clarity. His furniture no longer performs rococo movement for its own sake. It thinks, organizes, and anticipates.

Jean-Henri Riesener

Oeben’s pupil and successor, Jean-Henri Riesener (1734–1806), represents the natural evolution of the Transition style toward full neoclassicism. Appointed ébéniste du Roi in 1774, he refined the vocabulary inherited from his master while pushing it toward greater precision and decorative control.

Riesener’s marquetry, particularly his famous perspective cubes and highly structured floral compositions, reveals an exceptional sense of order. Surfaces are carefully articulated, volumes clearly defined, and ornament always placed with intention. Where rococo once flowed freely, Riesener introduces hierarchy and rhythm.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, author Ajc994, CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

His work illustrates how the Transition style did not disappear abruptly, but instead matured into the Louis XVI aesthetic. In Riesener’s hands, balance becomes discipline, and elegance becomes architecture.

Roger Vandercruse, known as Lacroix

Roger Vandercruse, active in Paris between 1728 and 1799 and signing his works RVLC, excelled in small-scale furniture of great refinement. Writing tables, bonheurs-du-jour, and light commodes formed the core of his production, objects designed for intimacy rather than state display.

His work captures the most graceful side of the Transition style. Louis XV elegance is still present, but it is tempered by a growing sense of order. Floral marquetry becomes more stylised, bronzes more restrained, proportions more controlled. Everything feels deliberate, yet never stiff.

Lacroix’s furniture speaks to a cultivated clientele. It is refined without ostentation, sophisticated without heaviness. In many ways, it defines the Transition style as lived in private interiors rather than ceremonial spaces.

Pierre Gouthière

A brilliant chaser-gilder, Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813) transformed the role of bronze in furniture. His work marks a decisive shift away from rococo exuberance toward a more architectural and classical language.

Gouthière replaced restless rocailles with antique-inspired motifs: laurel wreaths, palmettes, beading, and finely modelled friezes. His bronzes do not overwhelm the furniture they adorn. Instead, they articulate its structure, underline its geometry, and give rhythm to its surfaces.

Highly sought after by Madame du Barry and the aristocratic elite, Gouthière’s work bridges the emotional warmth of rococo craftsmanship with the intellectual clarity of neoclassicism. His bronzes feel alive, yet controlled, a perfect parallel to the Transition style itself.

Madame de Pompadour

Madame de Pompadour played a decisive role in shaping the taste of her time. More than the king’s favourite, she was a cultivated patron, deeply interested in the arts, architecture, and antiquity. Her influence extended far beyond the private sphere.

Through her support of artists, architects, and craftsmen, she encouraged a gradual return to classical order. Her brother, the Marquis de Marigny, appointed Director of the King’s Buildings, institutionalised this shift by favouring symmetry, archaeological references, and clarity in royal commissions.

Together, they helped create the cultural conditions in which the Transition style could flourish. Not as a rebellion, but as a thoughtful reorientation of taste.

Architecture

Petit Trianon, Versailles

Commissioned by Louis XV for Madame de Pompadour and completed in 1768 by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, the Petit Trianon stands as one of the clearest architectural expressions of the Transition style. Its composition is rigorous, its volumes perfectly balanced, and its façades governed by symmetry and proportion.

The language is unmistakably classical. Corinthian pilasters, rectilinear façades, and a strict geometric order announce the coming of neoclassicism. Yet the building never feels austere. The scale remains intimate, the proportions delicate, and the overall effect refined rather than monumental.

The Petit Trianon does not reject the elegance of the Louis XV period. It distils it. It transforms rococo grace into architectural clarity, offering a perfect parallel to what cabinetmakers were achieving in furniture at the same moment.

Place de la Concorde, Paris

Designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel between 1755 and 1775, the former Place Louis XV marks a decisive moment in Parisian urban design. Conceived as a vast, symmetrical ensemble, it abandons rococo irregularity in favour of classical order and legibility.

The monumental colonnades framing the square introduce a Greek-inspired vocabulary into the heart of the city. The composition is axial, measured, and controlled. Ornament gives way to architecture, and spectacle is replaced by structure.

This project illustrates how the Transition style was not limited to interiors or furniture. It reshaped the urban landscape itself, preparing the ground for the neoclassical city of the late 18th century.

École Militaire, Paris

Built between 1751 and 1773, also under the direction of Gabriel, the École Militaire reveals how the Transition style operated at a monumental scale. The composition is sober, symmetrical, and clearly articulated, yet still carries a sense of grandeur inherited from earlier royal architecture.

The cour d’honneur, flanked by orderly pavilions and crowned by a classical dome, expresses authority without excess. The decorative language is restrained, favouring proportion and clarity over surface ornament.

Here, the Transition style becomes institutional. It demonstrates that classical discipline could serve power, function, and representation, without abandoning elegance.

Overview of the central building within a vast complex commissioned by Louis XV and designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel.

Furniture & Representative Objects

Seating in the Transition Style

During the Transition period, French seating underwent a subtle but decisive transformation. Armchairs, bergères, and chairs retained the comfort developed under Louis XV, with generous proportions and an ergonomics designed for conversation and salon life.

Structurally, however, change was underway. Lines became clearer, symmetry more pronounced, and backs increasingly geometric. The medallion backrest began to replace more fluid rococo outlines, while legs grew straighter and more disciplined, anticipating the Louis XVI vocabulary.

Ornament followed the same logic. Rocaille motifs faded in favour of discreet carving, linear mouldings, and early classical references. Transition seating is neither exuberant nor severe. It captures a moment of balance, where comfort and elegance are reorganised around architectural logic.

Desks and Writing Furniture

Between 1750 and 1770, the desk became a central object in elite interiors. Both functional and symbolic, it reflected new relationships to work, privacy, and intellectual life. Several types coexisted, revealing the richness of the Transition period.

The bureau plat, inherited from Louis XIV ceremonial furniture, grew lighter and more restrained. Lines straightened, legs refined, and bronzes adopted geometric or antique motifs. The cylinder desk, still rare but technically ambitious, embodied the virtuosity of the age, combining elegance with ingenious mechanisms.

At a more intimate scale, the writing table emerged as a distinctly modern object. Slim, elegant, and discreet, it was designed for private use rather than display. Ornament was reduced to stringing, friezes, or subtle bronze mounts, reinforcing the Transition ideal of controlled refinement.

By Joseph Baumhauer, cabinetmaker. A French piece that captures the shift from Louis XV rocaille toward the neoclassical clarity that would define Louis XVI.

The Bureau du Roi

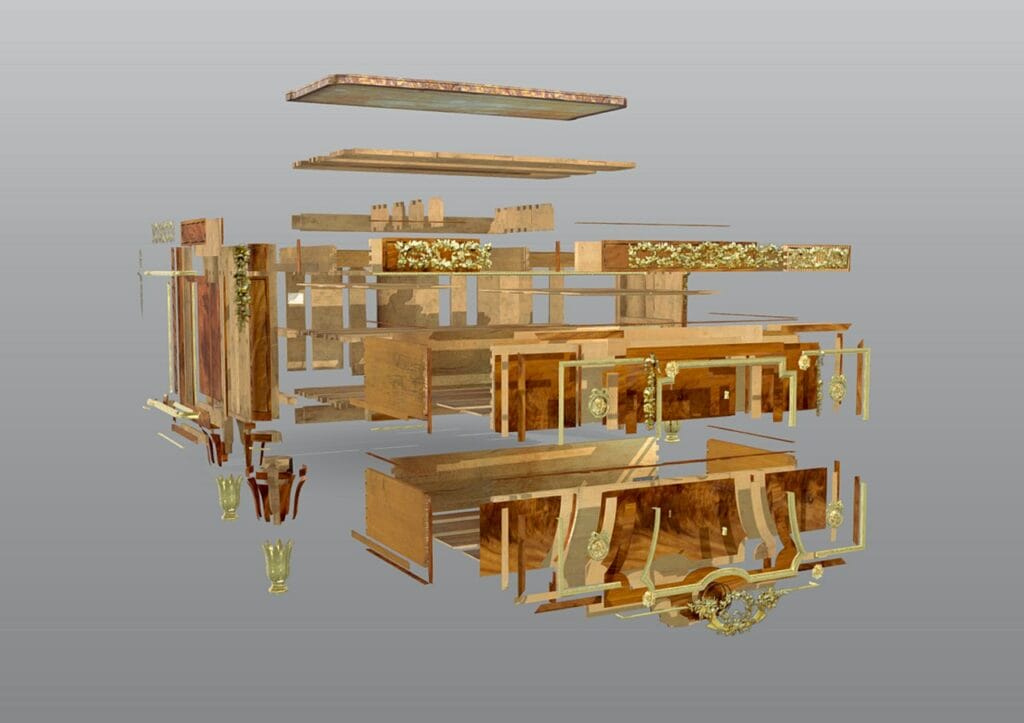

Commissioned by Louis XV in 1760, the Bureau du Roi remains the most iconic object of the Transition style. Conceived by Jean-François Oeben and completed by Jean-Henri Riesener, it synthesises technical mastery, decorative intelligence, and symbolic power.

Its marquetry combines floral motifs, trophies, and allegorical references to the arts and sciences. Hidden mechanisms, sliding panels, and a perfectly calibrated cylinder reveal a level of craftsmanship unmatched in European furniture of the period.

Preserved at Versailles, the Bureau du Roi stands as both a political object and a design manifesto. It shows how the Transition style could unite comfort, innovation, and classical order in a single, monumental piece.

Commode in the Transition Style

The Transition commode marks a clear departure from rococo exuberance. Curved fronts give way to flatter façades, corners sharpen, and vertical uprights assert a new architectural logic. The overall silhouette becomes calmer, more legible, and more rational.

Decoration remains refined. Gilt bronzes are used sparingly, placed at structural points rather than scattered across the surface. Marquetry becomes increasingly geometric, with perspective cubes and symmetrical compositions playing a central role.

A French piece blending Louis XV-inherited curves with a structure that foreshadows Louis XVI neoclassicism.

Among these pieces, the Greek style commode represents the most explicit classical turn. Straight lines dominate, legs are often fluted or tapered, and the decorative vocabulary draws directly from Antiquity. It is here that the Transition style most clearly announces Louis XVI.

Bonheur-du-jour

The bonheur-du-jour, a small and highly refined writing desk associated with feminine interiors, reached its peak during the Transition period. Light in structure and elegant in proportion, it was designed for private correspondence and personal use.

Typically composed of a writing surface topped by a tier of small drawers, sometimes concealed, the bonheur-du-jour balances functionality and delicacy. Tapered legs, restrained ornament, and precious materials give it an air of discreet luxury.

In the hands of makers such as Roger Vandercruse or Martin Carlin, often enhanced with Sèvres porcelain plaques, the bonheur-du-jour embodies the most intimate and cultivated face of the Transition style.

Secrétaire à abattant

The secrétaire à abattant occupies a central place in Transition furniture. Both architectural and intimate, it combines a strict, rectilinear façade with a refined interior revealed only when the fall-front is opened.

Behind the abattant, a carefully ordered composition of small drawers, pigeonholes, and compartments reflects the new taste for clarity and organisation. Marquetry favours geometric structures or stylised floral motifs, while bronzes are used sparingly to frame and articulate the form.

The secrétaire à abattant perfectly expresses the Transition spirit. It preserves the elegance and craftsmanship of Louis XV, yet introduces a sense of order and restraint that anticipates Louis XVI.

Wall appliques, bronzes, and decorative objects

Decorative objects of the Transition period reflect the same shift toward discipline and classical clarity. Wall appliques, cartel clocks, and gilt-bronze ornaments gradually abandon rococo agitation in favour of more legible silhouettes and antique-inspired motifs.

Forms become calmer. Lyres, urns, laurel wreaths, and tied ribbons replace shells and asymmetrical scrolls. Gilt bronze remains technically virtuosic, but its role changes. It frames, balances, and punctuates, rather than dominating the composition.

In the hands of masters such as Pierre Gouthière, bronze decoration reaches an exceptional level of refinement. These objects often function as transitional markers, visually linking late rococo interiors with emerging neoclassical spaces.

Legacy & Reinterpretations

The Transition style left a lasting imprint on European decorative arts by proving that stylistic evolution could occur without rupture. Its ability to reconcile two opposing aesthetics made it a reference point for later periods facing similar moments of change.

In the 19th century, both the Louis-Philippe style and the Second Empire occasionally revisited Transition forms, drawn to their balance and restraint. Parisian cabinetmakers produced high-quality reinterpretations, sometimes bordering on pastiche, yet often executed with remarkable skill.

Today, contemporary designers continue to draw inspiration from the Transition mindset. Not its ornament, but its logic. The idea that elegance can emerge from synthesis rather than opposition remains deeply relevant.

Market Value & Collecting Today

Buying new

Authentic re-editions of Transition furniture are rare. A small number of French master cabinetmakers still work according to traditional techniques, producing museum-quality pieces on commission. A newly made Transition-style commode can range from €30,000 to €80,000, depending on the complexity of the marquetry and the quality of the bronzes.

Specialised galleries such as Kraemer or Galerie Aveline in Paris occasionally offer both period pieces and exceptional contemporary interpretations, with full guarantees of authenticity and conservation-grade restoration.

Antiques and auctions

The market for original Transition furniture remains highly active. A stamped commode by Oeben or Riesener can exceed €500,000 at auction. Smaller pieces, such as writing tables or bonheurs-du-jour, typically range from €15,000 to €150,000, depending on provenance and condition.

Transition seating, rarer than case furniture, is particularly sought after. Pairs of stamped armchairs can reach €5,000 to €50,000. At major auction houses such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s, or Hôtel Drouot, provenance often plays a decisive role in final prices.

Conclusion

The Transition style represents one of the most refined moments in French decorative arts. Neither nostalgic nor revolutionary, it demonstrates how taste can evolve through adjustment rather than rupture.

Its short lifespan, barely a quarter of a century, explains both its rarity and its enduring appeal. Without this subtle rebalancing of form, the leap from rococo exuberance to neoclassical rigour would have felt abrupt, even incoherent.

Today, the Transition style continues to resonate. It reminds us that innovation does not require erasure. It can emerge from continuity, provided proportion, intelligence, and craftsmanship remain at the centre of the design process.

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.