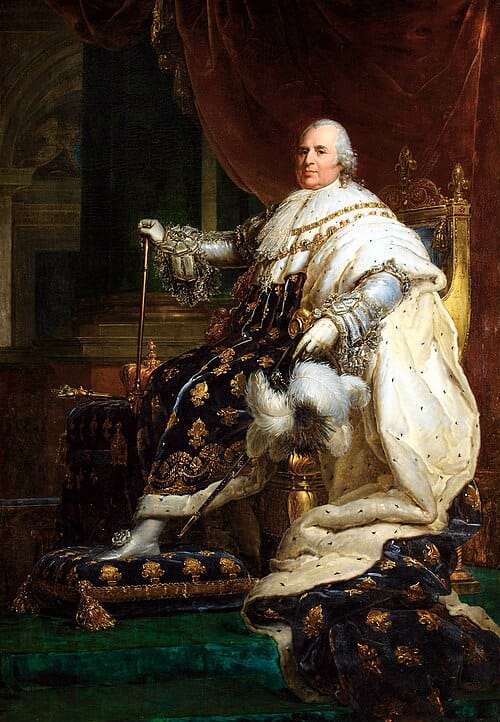

Louis-Philippe Style: The Bourgeois Art of Living (1830–1848)

The Louis-Philippe style (1830–1848) is the first French decorative language truly shaped for the modern bourgeois home. It favours comfort, practicality, and restrained elegance, stepping away from the theatrical display of power inherited from the Empire.

What is the Louis-Philippe style?

The Louis-Philippe style refers to the decorative and furniture forms developed in France between 1830 and 1848, during the July Monarchy. It reflects a profound shift in lifestyle: interiors stop functioning as aristocratic or political statements and become rational domestic spaces, designed for everyday life.

Born from the transition between the Empire and the later Second Empire, Louis-Philippe turns away from monumentality, antique references, and imperial solemnity. In their place come softer lines, more embracing volumes, and furniture built around use. Shapes become rounded, proportions settle, and ornamentation retreats into a quieter role.

This style rises alongside an urban bourgeoisie that values stability, respectability, and comfort. Louis-Philippe furniture -armchairs, sofas, chests of drawers, secretaries – prioritises solid construction, readable function, and careful execution. Dark woods such as mahogany and walnut dominate; decoration stays controlled; silhouettes remain balanced. More than a transitional moment, Louis-Philippe lays the groundwork for the modern interior. It introduces an aesthetic of lasting comfort, measured elegance, and lived-in practicality. Those are the principles that would shape the bourgeois home of the nineteenth century and, more broadly, many of our interiors today.

The Louis-Philippe Style: The Rise of the French Bourgeoisie

If the Louis-Philippe style reshapes Western decorative culture, it does so by affirming the triumph of the bourgeoisie and the flourishing of decorative eclecticism. This aesthetic turn mirrors the social evolution of mid-nineteenth-century France: from aristocracy to the middle class, from court display to a more widely shared ideal of family comfort. The July Monarchy invents an art of living that reconciles industrial prosperity with multiple historical references.

Quiet but decisive, this revolution changes the way we understand accessible luxury and eclectic decorative taste. The Louis-Philippe style sketches an early future for democratic design, putting comfort above ceremony and function above protocol.

Louis-Philippe: The Creative Expansion of Eclectic Taste

Across eighteen years marked by industrial progress and a broader diffusion of taste, the period transforms French and European decorative arts, setting new standards for bourgeois comfort.

A defining timeline:

1830–1848: Reign of Louis-Philippe (18 years)

1830: July Revolution, the rise of a confident bourgeois society

1848: February Revolution, end of the July Monarchy

The Comfort Revolution

The era disrupts the codes of aristocratic decorative culture. Creators respond to new bourgeois markets, while an emerging industrial middle class becomes a key prescriber of a more widely shared European taste.

Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois, Charles-Guillaume Diehl, and the Maison Krieger embody this creative shift—one that would leave a lasting mark on Western decorative arts.

The rise of industrial society changes everyday life. Railways, the textile industry, and bourgeois prosperity inspire an aesthetic that celebrates social success and domestic harmony.

That social transformation produces a new visual language—one that still informs contemporary ideas of democratic design and approachable art de vivre.

A Revolution of Form and Practicality

Now it is the cabinetmakers turned industrial entrepreneurs who help define modern taste, replacing aristocratic exclusivity with the logic (and the ambition) of serial production.

The period forges a new alliance between craft tradition and industrial innovation, between French quality and a new kind of accessibility. In doing so, it broadens the reach of bourgeois comfort and redefines the domestic ideal.

Louis-Philippe aesthetics blur the line between luxury and practicality. Eclectic references, varied materials, and optimised comfort speak to a pragmatic modernity.

Arts: The Avant-Garde of Wider Access

Paris and Europe as Laboratories of Bourgeois Taste

In the 1830s and 1840s, Parisian decorative arts synthesise inherited styles into an eclectic language with striking coherence.

Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois (a master of eclectic cabinetmaking), Charles-Guillaume Diehl (a virtuoso of bourgeois marquetry), and Maison Krieger (an innovator in serial production) help define this new aesthetic.

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc reshapes historic architecture, Paul Delaroche influences the decorative imagination through his reconstructions, while Ingres explores the expressive potential of the bourgeois portrait.

A Renewed and Expanding World of Craft

Louis-Philippe style revitalises French decorative trades by adapting them to industrial production and redirecting them toward a broader bourgeois audience.

Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois (historicist cabinetmaking), Charles-Guillaume Diehl (marquetry at scale), and François Linke (modern techniques) each rework their craft for a changing world.

Bronze workshops modernise with Ferdinand Barbedienne and Christofle, developing an ornamental language of wider, newly attainable richness.

Silversmithing reaches new markets through Charles Christofle and Odiot, while the Sèvres manufactory develops Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Gothic decorative programmes.

Tapestry evolves as well, with eclectic Gobelins production expanding into a decorative vocabulary shaped by bourgeois diversity.

Louis-Philippe Architecture: A Bourgeois Manifesto of Modernity

The Bourgeois Townhouse as Innovation: A Laboratory for Comfort

A defining shift: the bourgeois townhouse turns architecture into a manifesto of more widely shared art de vivre.

This revolution introduces new architectural standards: rational planning, family comfort, and a newly legitimised decorative eclecticism.

Key Figures of French Architecture

Architect Félix Duban, a major figure in eclectic architecture, develops a historicist aesthetic that influences modern European architecture at large.

Henri Labrouste (innovator of iron architecture), Louis Visconti (bourgeois urbanism), and Théodore Ballu (religious eclecticism) embody this French avant-garde.

Celebrated internationally, this architectural culture lays foundations for bourgeois living and inspires expanding European cities.

It reshapes ideas of democratic housing and establishes French eclecticism as a durable bourgeois reference.

A Total Decorative Vision

Louis-Philippe style helps define a form of eclectic art de vivre, where architecture, furniture, decorative objects, and textiles form a coherent whole, serving optimised bourgeois comfort.

Figures such as Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois, Charles-Guillaume Diehl, and Ferdinand Barbedienne refine the art of eclectic decorative synthesis.

The Synthesis of the Arts

Louis-Philippe codifies a decorative vocabulary that travels across Europe: historic eclecticism, multiple references, and modern comfort.

Paul Delaroche (history painting) and Horace Vernet (historical scenes) influence the applied arts through new forms of visual storytelling.

The impact of triumphant historicism and French tradition encourages a learned eclecticism that shapes bourgeois inspiration across Europe.

Furniture arts become more attainable through Barbedienne’s bronzes and industrial cabinetmakers, who produce objects of refined, newly accessible sophistication.

Porcelain finds a bourgeois expression through Sèvres’ eclectic creations, developing a tableware culture marked by democratised richness.

Louis-Philippe Furniture: The Birth of Bourgeois Comfort

Louis-Philippe furniture marks a decisive turning point in the history of French design. For the first time, form is no longer dictated by the staging of power, but by everyday use, domestic comfort, and durability. Furniture becomes stable, welcoming, and made for family life.

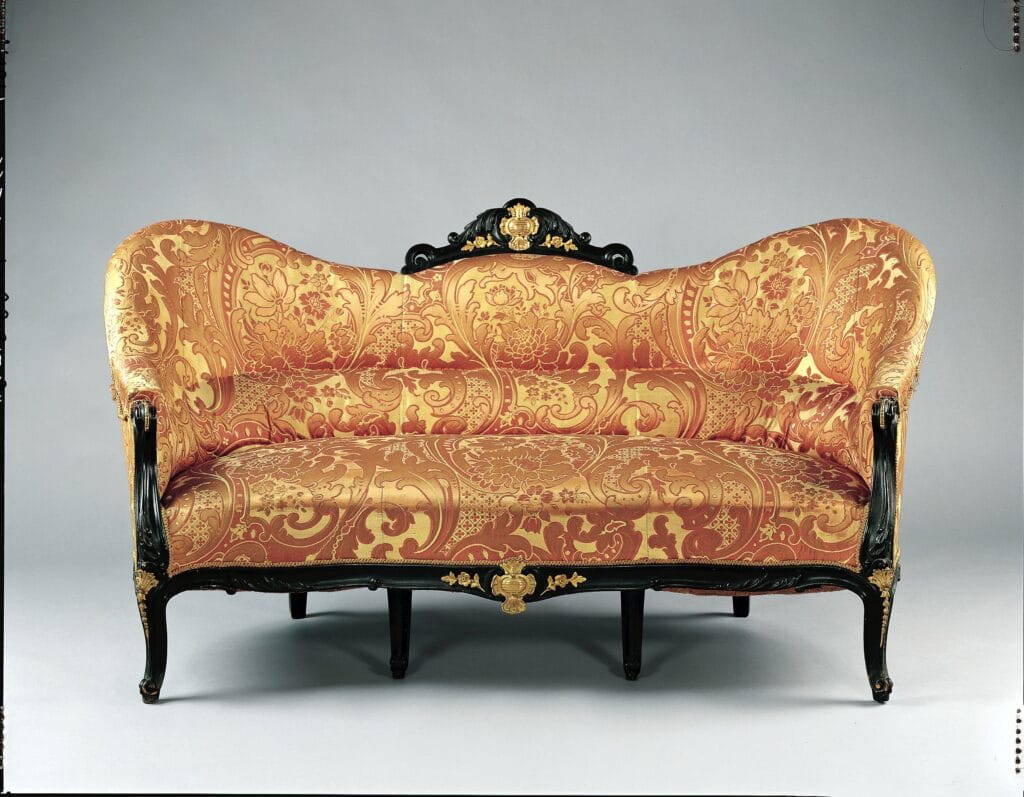

Lines soften, volumes widen, and proportions find a new balance. Ornament is still present, yet kept in check. It follows the form rather than overpowering it. That measured approach clearly sets Louis-Philippe apart from the Empire style while foreshadowing the more demonstrative opulence of the Second Empire.

Forms, Silhouettes, and Woods

The formal vocabulary of Louis-Philippe furniture is built on full silhouettes, cabriole legs, embracing backs, and generous armrests. Sharp edges give way to continuous curves, designed to feel right against the body.

The preferred woods reflect bourgeois taste for solidity and quiet status:

- Mahogany: a signature wood, stable and elegant

- Walnut: warmer in tone, widely used in French interiors

- Dark veneers: used to harmonise matching sets of furniture

Louis-Philippe Furniture Types

Louis-Philippe develops a complete typology of domestic furniture, aligned with new bourgeois habits. These pieces avoid spectacle. They project reassurance and permanence. Built to be used, passed down, and repaired, they belong to the long run.

Louis-Philippe Tables

Under Louis-Philippe (1830–1848), the table becomes a versatile and practical piece, designed for bourgeois domestic routines.

The main types include salon tables, work tables, game tables, and dining tables. They are recognised by cabriole or turned legs, understated tops, and stable proportions. Ornament remains discreet; strength, balance, and daily use come first.

Louis-Philippe Consoles

The Louis-Philippe console is a restrained, well-structured occasional piece for entrances and salons. Typically rectangular, its top is often dark wood or marble. Legs are cabriole or turned, sometimes joined by a stretcher. Decoration stays minimal, with balance and function taking precedence over display.

Louis-Philippe Secretaries

The Louis-Philippe secretary is an emblem of bourgeois life. Whether with a fall-front or drawers, it is made for writing, correspondence, and storage. The body feels substantial; fronts are gently curved; ornament is discreet. It embodies a rational, elegant, durable aesthetic fully aligned with everyday use.

Louis-Philippe Chests of Drawers

The Louis-Philippe chest of drawers favours softened mass and gentle curvature. Usually with three or four drawers, it is crafted in mahogany or walnut, sometimes finished with dark veneer. With little decoration, it relies on solidity, clarity, and stability answering practical needs in the bourgeois home.

Louis-Philippe Beds

The Louis-Philippe bed is defined by full, balanced forms. The headboard and footboard are typically of similar height, sometimes subtly curved. Made in dark wood (mahogany or walnut) it favours sturdiness and restraint. Decoration remains minimal, often limited to simple mouldings, leaving textiles (curtains, coverlets, hangings) to bring warmth and comfort to the bourgeois bedroom.

A Typology of Louis-Philippe Seating

Under Louis-Philippe (1830–1848), seating comes in clearly identifiable types: gondola-back armchairs, bergères with solid side panels, more restrained cabriolet armchairs, salon chairs with full backs or softened medallion shapes, and sofas that are straight or subtly bowed. They share the same core traits: embracing backs, deeper seats, sturdy frames, and a direct pursuit of comfort made for bourgeois interiors.

The Voltaire Armchair: The Birth of a Comfort Icon

The Voltaire armchair appears in the mid-nineteenth century, at the end of the Louis-Philippe period, before spreading widely under the Second Empire.

Recognisable by its tall, straight back—sometimes with side “wings”—and its deep seat, it is designed for reading and rest. It naturally extends Louis-Philippe seating by pushing the pursuit of bourgeois comfort even further.

In that sense, it becomes one of the first fully modern armchairs: a symbol of durable bourgeois comfort, and one of the most instantly recognisable seats in Western furniture history.

Cabinetmakers and Serial Production

Louis-Philippe furniture grows alongside the rise of cabinetmakers-turned-industrial producers, capable of delivering quality pieces in greater quantities. Houses such as Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois, Charles-Guillaume Diehl, and Krieger refine serial production while maintaining a high level of execution.

Mechanised veneers, standardised ornamental bronzes, simplified marquetry: these innovations support a wider access to well-made furniture without sacrificing French elegance.

A Lasting Legacy

Louis-Philippe furniture stands among the foundations of the modern interior. It introduces a new definition of the domestic object: stable, comfortable, rational, designed for real life rather than representation.

Its influence extends well beyond 1848, feeding both the Second Empire and certain contemporary approaches to comfort, modular living, and durable domestic design.

Louis-Philippe Textiles: Decorative Art Made More Accessible

Materials and Textures: A New Reach

Louis-Philippe style transforms textile culture by favouring a broader diffusion of luxury and a richer variety of materials. French manufactures develop industrial techniques that turn textiles into decorative elements that are more attainable and more diverse.

Lyon silks, adapted to a wider market: Lyonnais silks respond to bourgeois demand with less complex weaves that are more affordable. Brocaded silks integrate varied historical motifs, creating decorative effects of newly attainable richness.

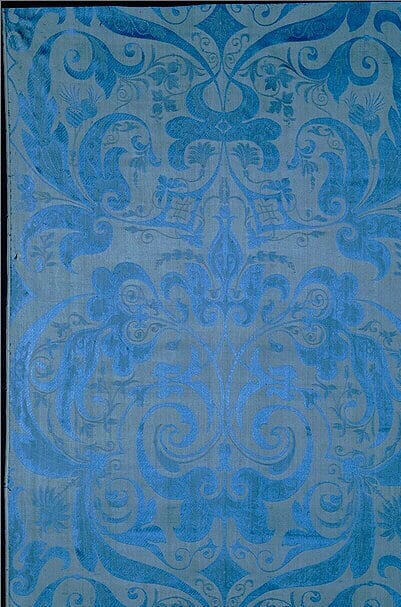

Serial damasks: Damasks develop repeat patterns that support scale production, delivering decorative impact with a democratised quality.

Reps and carpets: A Louis-Philippe innovation, these robust furnishing textiles offer a bourgeois form of durability aligned with family life.

Printed cottons: Toile de Jouy and printed “Indiennes” become more widely available, introducing a decorative variety that renews bourgeois textile ornament.

Colour: The Invention of a Bourgeois Palette

Louis-Philippe colour culture develops an eclectic palette, drawing from multiple legacies to match an increasingly varied bourgeois taste.

Signature tones:

- Mahogany brown: a deep wood tone, emblematic of bourgeois solidity

- Burgundy red: a dark red expressing prosperity and a taste for comfort

- Bronze green: a metallic green echoing the era’s furniture bronzes

- Muted gold: less brilliant gilding, more restrained and in tune with bourgeois interiors

Sophisticated harmonies favour rich, controlled contrasts: brown with gold, red with green, blue with bronze combinations that create an atmosphere of measured bourgeois elegance.

Motifs and Iconography: A Triumphant Eclectic Vocabulary

Louis-Philippe textile ornament develops an iconographic repertoire drawing on historic styles to satisfy bourgeois eclecticism.

Historicist motifs:

- Neo-Renaissance: arabesques, cartouches, cut-leather effects inspired by the sixteenth century

- Neo-Gothic: trefoils, rosettes, idealised medieval architectural motifs

- Neo-Rococo: an eighteenth-century revival adjusted to bourgeois taste

- Orientalism: Turkish, Persian, and Chinese motifs shaped by colonial horizons

Bourgeois iconography:

- Genre scenes: representations of bourgeois family and social life

- Picturesque landscapes: romantic views that decorate the bourgeois interior

- Industrial motifs: early references to technical innovation (railways, machines)

The Rise of Passementerie

Passementerie is everywhere: curtains, cushions, trims. The craft of trimmings expands and becomes more widely accessible. The Louis-Philippe era also foreshadows the golden age of passementerie that will fully unfold under the next style: Napoleon III.

Techniques and Know-How: Industrial Innovation

Industrialised weaving: looms become mechanised, enabling serial decorative effects.

Evolution and Influences: Toward the Second Empire

From around 1845 onward, Louis-Philippe textiles begin to shift under the influence of an emerging Second Empire taste.

Which decorative movement follows Louis-Philippe?

After Louis-Philippe (1830–1848), the evolution leads toward:

1. Napoleon III Style / Second Empire (1852–1870) 🇫🇷

Country: France

Key traits: opulent eclecticism, multiple references, imperial comfort

2. Victorian Style (1837–1901) 🇬🇧

Country: United Kingdom

Key traits: British eclecticism, bourgeois comfort, Gothic references

3. Late Biedermeier (1840–1860) 🇦🇹🇩🇪

Countries: Austria, Germany

Key traits: evolved bourgeois simplicity, family comfort, lighter woods

4. Late American Federal style (1840–1860) 🇺🇸

Country: United States

Key traits: American eclecticism, democratic comfort, multiple European inspirations

Digital entrepreneur and craft artisan.

My work bridges craftsmanship, design history and contemporary creation, shaping a personal vision of luxury interior design.

Since 2012, I have been based in my workshop on the shores of Lake Annecy, creating bespoke interiors for architects, decorators and private clients.