Art Nouveau (1900–1914): A Brief Renaissance of Emotion and Form

1900 – “The fire ignites in the spirit” – Le Corbusier

A creative fire indeed—one that swept across Europe, taking root in England as Modern Style, in France as Art Nouveau, in Germany as Jugendstil, and in Austria as Secessionsstil. While critics derided it as “noodle style,” “metro style,” or even “tapeworm style,” its legacy endures. Once dismissed, this ornamental and poetic aesthetic has returned to the forefront, reclaiming its place among the great decorative revolutions.

What is Art Nouveau?

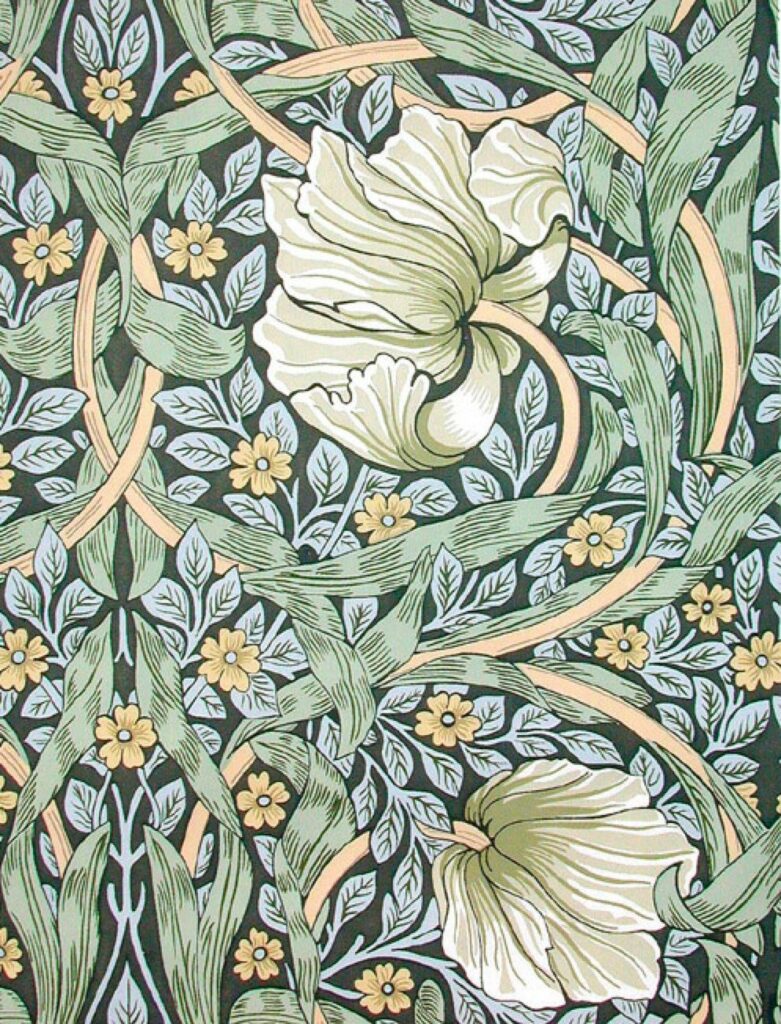

Art Nouveau, also known as Modern Style, draws directly from nature—rejecting straight lines in favor of curves, vines, petals, and organic forms. Its decorative vocabulary is rooted in the botanical: ivy, wisteria, irises, umbels, and other flora are woven into a dreamlike language of interiors.

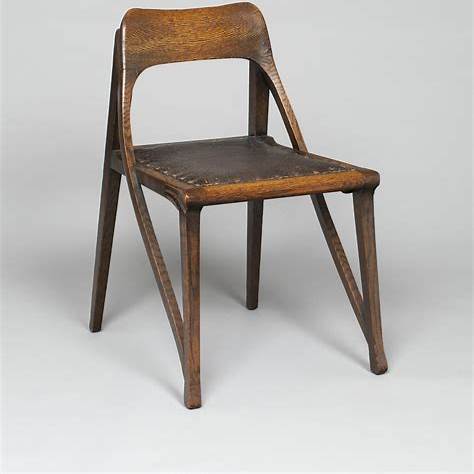

It is an art form that fuses folklore, exoticism, literature, naturalism, and fantasy. Furniture is sculpted like living organisms—its flat surfaces only permitted when inlaid with marquetry, landscapes, or floral motifs that evoke paintings. Everyday objects like vases and lamps bloom into tulips, cyclamens, and irises. Textiles and wallpapers fill interiors with color and natural light, transforming the domestic into the enchanted.

Yet this blossoming was fleeting. Even before the First World War, a new, pared-down aesthetic began to emerge. After the war, it would flourish in the form of Art Deco—leaving Art Nouveau, briefly admired, to be discarded, forgotten, or relegated to attics.

Symbolist Echoes & Romantic Influences

Art Nouveau is deeply connected to Symbolism, the literary and artistic movement of the fin-de-siècle. Its dreamlike, musical, and sometimes mystical sensibilities inspired painters like Gustav Klimt in Vienna and Gustave Moreau in Paris. The femme fatale—sinuous, disheveled, and often surrounded by serpentine florals—was a dominant motif of the era.

There is also a profound influence from Gothic and medieval craftsmanship, championed by Viollet-le-Duc, who argued for organic, living structures over the static symmetry of classical architecture. His vision would deeply inspire Gaudí, Guimard, and the École de Nancy.

Art Nouveau Across Europe

From England to Spain and Belgium, Art Nouveau unfolded in striking regional styles. In England, William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement pioneered a spiritual return to craftsmanship. In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí turned architecture into organic fantasy—rejecting the straight line, adorning his buildings with colorful trencadís and biomorphic forms, and fusing structure with nature. Casa Batlló’s undulating façade and dragon-scale roof epitomize his visionary aesthetic. In Belgium, Victor Horta introduced the “whiplash line,” turning interiors into flowing, harmonious environments.

In England

In the industrial heart of England, resistance to machine-made ugliness began with the Arts & Crafts movement. Visionary thinkers like John Ruskin called for a return to medieval craftsmanship, where faith, nature, and human touch imbued objects with beauty.

Artists like Edward Burne-Jones and especially William Morris—who left painting behind to dedicate himself to decorative arts—embodied these ideals. Morris’s textile and wallpaper patterns (from 1880 onward) laid the groundwork for what would become the Modern Style.

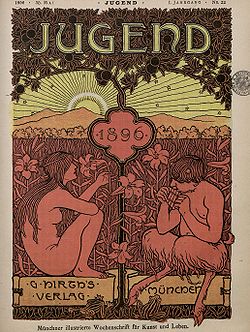

Jugendstil – The German Soul of Art Nouveau

Often misunderstood or overlooked, Jugendstil is essentially the German counterpart of Art Nouveau, emerging in the 1890s and blooming through the early 20th century. Though the name literally means “Youth Style”, Jugendstil was anything but immature—it was a bold, ideologically driven movement that sought to renew art, design, and society.

The term itself comes from “Jugend”, a progressive Munich-based art magazine founded by Georg Hirth in 1896. Inspired by England’s Arts & Crafts movement and the social ideals of John Ruskin and William Morris, Jugendstil designers envisioned a world where design could elevate everyday life and express a new ethical, aesthetic sensibility.

Key figures such as Hermann Obrist, Richard Riemerschmid, August Endell, and Otto Eckmann translated these ideals into interiors, furniture, typography, and architecture. Nature’s influence is unmistakable: curving lines, vegetal motifs, and the iconic whiplash line make frequent appearances, echoing the pan-European Art Nouveau vocabulary.

But Jugendstil also forged its own path. German artists went further than their French counterparts in trying to bridge the divide between industry and craft, advocating for a new kind of creative labor that resisted both mass-market banality and elitist art-for-art’s-sake detachment.

The movement resonated particularly strongly as Berlin attempted to impose a centralized Imperial aesthetic. In response, Jugendstil became a cultural rallying point for regional identity and artistic independence—especially in cities like Munich, Weimar, Dresden, and Hagen. It was not just a style, but a statement: the beauty of new forms could shape a new society.

L’École de Nancy – The French Art Nouveau Heartbeat

In France, the École de Nancy stands as the soulful epicenter of Art Nouveau. Founded by Émile Gallé, Louis Majorelle, and the Daum brothers, this movement embraced nature as both muse and method. In their hands, dragonflies, orchids, and algae were not mere motifs, but symbols of life’s fragility and beauty. Glass, wood, iron, and fabric were transformed into organic marvels—each piece unique, alive, and expressive. Their approach was total: furniture, ceramics, textiles, and lighting worked together to create an immersive, harmonious interior world. The French version of Art Nouveau, deeply rooted in artisanal values and symbolism, remains one of the most emotionally resonant expressions of the movement.

The aesthetics of Japan and China captivated artists and artisans alike. In Nancy, under the visionary Émile Gallé, japonisme fused with floral inspiration and rococo memory to shape a new decorative language that helped define Art Nouveau’s French incarnation.

In Belgium

Belgium birthed a more sensual Art Nouveau, with architects Victor Horta, Paul Hankar, and Henry van de Velde pioneering the dynamic whiplash line—a sinuous, electrified curve that defined everything from stairwells to iron railings. Horta’s Hôtel Tassel in Brussels (1892–1893) remains an icon of this expressive architecture.

In Spain

In Spain, Art Nouveau blossomed under the name Modernisme Català, taking root in Barcelona as both an artistic revolution and a cultural affirmation. Far from simply mimicking the French or Belgian schools, Catalan Modernisme fused architecture, decorative arts, and national identity. Antoni Gaudí was its most visionary voice—his architecture defied the straight line, adopting biomorphic curves, shimmering mosaics (trencadís), and structural fluidity drawn from nature itself. But he was not alone: Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Josep Puig i Cadafalch also contributed to a deeply symbolic and poetic vision of space, where ornament and structure merged into spiritual narrative.

Modernisme was not limited to buildings—it touched furniture, stained glass, ironwork, and urban design. More than a style, it was a worldview: deeply Catholic, often mystical, and grounded in a Mediterranean sense of material sensuality. Through this unique prism, Spanish Art Nouveau became an immersive, lyrical experience—alive with motion, color, and light.

In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí transformed the city into a fever dream of ornament and structure. His architectural visions—like Casa Batlló (1904–1906)—remain among the most poetic manifestations of Art Nouveau in Europe.

Art Nouveau Interiors: Sculpture Meets Decoration

Some Art Nouveau furniture pieces are closer to sculpture than traditional woodworking—such is the case with Rupert Carabin’s creations. François‑Rupert Carabin (1862–1932) was a visionary sculptor‑cabinetmaker whose creations blurred the boundaries between furniture, sculpture, and storytelling. Influenced by his training in anatomy and photography—particularly studies of dancers and performers—Carabin sculpted living, moving forms into wood, bronze, ceramics, and metal

Designers like Georges Hoentschel, a trained upholsterer and decorator, designed interiors for aristocrats and royals alike—from Parisian tastemakers to the King of Greece and the Emperor of Japan.

Art Nouveau was more than a style—it was a total environment where furniture, fabrics, wallpapers, and lighting converged into a seamless, poetic unity.

Influences of Art Nouveau / Modern Style

| Influence | Description | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Nature (botany & zoology) | Plants, flowers, insects, animals | Organic forms, curved lines, whiplash motifs |

| Arts & Crafts Movement (England) | Led by William Morris, John Ruskin | Handcraftsmanship, anti-industrial values, decorative patterning |

| Symbolism | Literary & artistic movement (Moreau, Klimt) | Mystical and erotic undertones, dreamlike imagery |

| Gothic Revival / Medievalism | Championed by Viollet-le-Duc | Structural innovation, ornament, verticality |

| Japanese Art (Japonisme) | Ukiyo-e prints, asymmetry, line purity | Stylized forms, nature themes, surface design |

| Celtic & Nordic motifs | Mythical and symbolic forms | Intertwined patterns, animal figures, spiritual resonance |

| Islamic & Moorish ornament | Arabesques, tilework, geometry | Non-figurative decoration, intricate surfaces |

| Rococo Revival | Curved furniture, fluid decoration | Feminine grace, sensuality, asymmetry |

| Industrial materials & techniques | Iron, glass, concrete | Fluid architecture, transparency, integration of function |

| Photography & anatomy | Especially in France and Belgium | Study of movement, used in sculpture/furniture |

| Regional vernacular arts | Folk traditions in Catalonia, Nancy, etc. | Floral, folkloric motifs, integrated craftsmanship |

| Literature & philosophy | Baudelaire, Nietzsche, Ruskin | Mood, symbolism, spiritual aesthetics |

| Viennese Secession | Klimt, Hoffmann, Olbrich | Geometric stylization, fusion of art and architecture |

| Aestheticism / Art for Art’s Sake | Whistler, Beardsley, Pater | Style, surface refinement, beauty as value |